Key Takeaways

- Improved Forest Management (IFM) changes how existing forests are managed to increase carbon storage, rather than planting new forests or stopping deforestation, and is now one of the major forest credit types in the voluntary carbon market.

- Most legacy IFM credits have integrity issues around baselines, additionality, permanence, and leakage; only a small fraction of projects meet a standard that is defensible under CSRD and SBTi scrutiny.

- Next-generation IFM methodologies such as Verra VM0045 and ACR IFM v2.1, now CCP-approved by ICVCM, directly address some of the historic flaws but still require project-level due diligence.

- Sustainability leaders can use a structured 5-step evaluation process to vet IFM projects, focusing on methodology, baseline realism, buffer design, independent verification, and documented co-benefits.

- High-quality IFM credits can play a clear, CSRD-ready role as beyond value chain mitigation within an Oxford-aligned portfolio, especially when pre-screened using frameworks like Senken's 600+ data point Sustainability Integrity Index.

If you've been following the forest carbon credit conversation lately, you've probably noticed a shift. REDD+ projects are under fire, buyers are demanding removals, and a lot of attention is landing on something called Improved Forest Management—or IFM. But what exactly is IFM, and why should it matter to you right now?

Improved Forest Management (IFM) is a category of forest carbon credits that increases carbon storage in existing managed forests by changing how they're harvested or maintained. Unlike planting new trees or preventing deforestation, IFM keeps working forests working—just with better practices that lock up more carbon over time. It's become one of the largest nature-based credit types in the voluntary carbon market, accounting for nearly 30% of nature-based issuance in 2025.

Here's the reality: IFM is powerful when it's done right, but the market is flooded with legacy credits that don't hold up under audit. With CSRD reporting requirements tightening and boards asking harder questions, you need to know how IFM carbon credits actually work, where the quality problems sit, and how to safely use the small subset of high-integrity IFM in your strategy. This guide walks you through the mechanism, the risks, and the practical steps to evaluate projects before you buy.

What Is Improved Forest Management (IFM)

Plain-Language Definition and Scope

Improved Forest Management (IFM) changes how existing forests are managed to increase carbon storage, rather than planting new forests or stopping deforestation. In practical terms, IFM projects keep more trees standing for longer by extending harvest rotations, reducing cutting intensity, or legally restricting future harvest through conservation easements. The extra biomass that accumulates over time, compared to a business-as-usual logging scenario, is the basis for carbon credits.

Unlike afforestation projects that create new forest on bare land, or REDD+ projects that protect forests facing imminent deforestation threats, IFM works within the existing commercial forestry system. The forest was there before the project started, and it would have remained forest under the baseline scenario, but with higher harvest intensity and lower average carbon stocks.

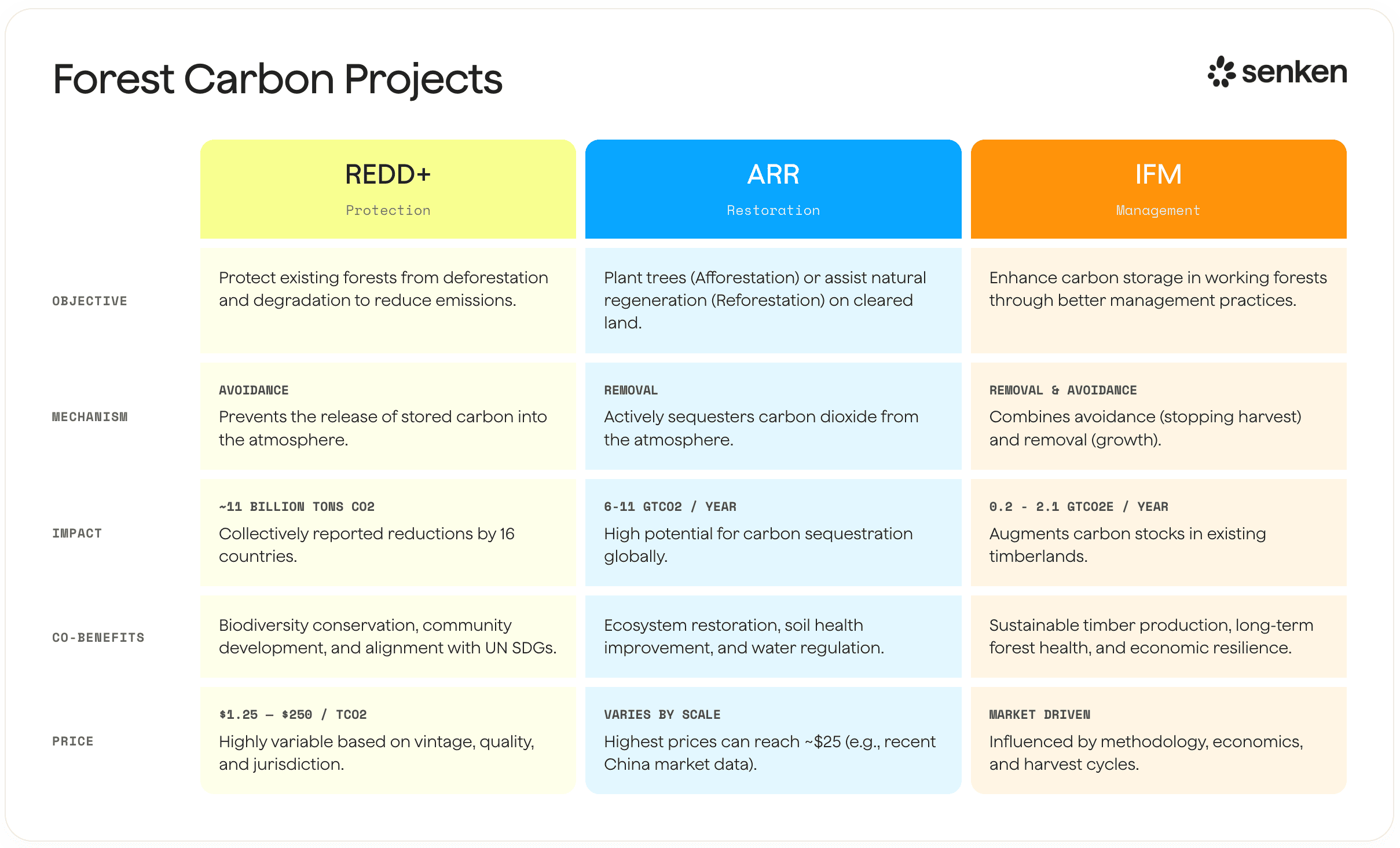

How IFM Differs From Other Forest Carbon Approaches

Understanding the distinction between IFM and other forest credit types is essential when building a defensible portfolio. REDD+ (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation) focuses on forests at risk of conversion to agriculture or development. The baseline threat in REDD+ is that the forest would be cut down entirely or severely degraded without intervention. In contrast, IFM baselines assume the forest will remain forest, but will be managed under standard commercial practices that involve regular harvesting.

Afforestation and reforestation (ARR) projects create new forests where there was none recently, or restore forests on long-degraded land. ARR delivers carbon accumulation from near zero starting stocks, but the ramp-up can take years or decades. IFM starts from an existing forest carbon stock and captures the incremental gain from managing it more conservatively.

This distinction matters for claim language, portfolio design, and risk. IFM can often deliver earlier volumes because the forest is already mature, but it requires airtight proof that the baseline harvest scenario was realistic and that the project intervention truly changed management decisions.

Why IFM Matters Now in the Voluntary Carbon Market

IFM has quietly become one of the most significant nature-based credit types in the voluntary market. Since 2008, IFM projects have issued roughly 193 million credits globally, representing about 28% of all forest-based offsets. Around 94% of these IFM credits are in the United States, and a large share fall under California's compliance offset programme alongside voluntary registries.

In 2024, while the broader voluntary carbon market contracted, IFM transaction volumes surged by 242% year-on-year, driven by buyers shifting away from controversial REDD+ projects and toward removal-labelled credits. By 2025, IFM accounted for nearly 30% of all nature-based credits issued. This growth reflects two dynamics: rising demand for removals to meet emerging SBTi and CSRD requirements, and the arrival of next-generation IFM methodologies that address historic integrity concerns.

Corporate buyers in Europe are increasingly looking at IFM because it offers a middle ground between short-lived nature-based options and expensive engineered removals. High-quality IFM can deliver carbon storage for 100+ years, clear co-benefits for biodiversity and water, and pricing that sits between avoidance credits and durable tech removals. However, only a small fraction of IFM supply meets the rigorous standards now expected under frameworks like ICVCM's Core Carbon Principles.

How IFM Carbon Credits Generate Climate Impact

Baseline Scenario vs. Project Scenario

Every IFM carbon credit rests on a comparison between two futures for the same forest. The baseline scenario represents what would have happened without the carbon project: continued commercial harvesting under typical practices, legal constraints, and market conditions. The project scenario describes the improved management that the project commits to: longer rotations, lighter thinning, or permanent conservation restrictions.

The difference in average standing carbon between these two scenarios, measured over a crediting period (often 30 to 100 years), determines how many credits can be issued. If the baseline assumes clear-cutting every 40 years and the project extends rotation to 80 years, the forest accumulates significantly more biomass over time, and that incremental stock is credited.

Baseline design is where most integrity issues arise. If the baseline overstates how aggressively the forest would have been cut, the project over-credits. Independent analyses of legacy U.S. IFM found that coarse regional averages for harvest intensity, combined with minimal evidence that landowners would truly have harvested at that rate, led to substantial over-crediting. This is why newer methodologies like Verra VM0045 use matched-plot baselines from national forest inventories and require dynamic re-assessment each reporting period.

How Carbon Storage Is Measured in IFM Projects

IFM projects quantify carbon through forest inventories, biomass equations, and carbon pool accounting. Project developers establish sample plots across the project area, measure tree diameter, height, and species, then apply allometric equations to estimate total biomass. That biomass is converted to carbon (roughly 50% of dry biomass by weight) and reported across multiple pools: aboveground live biomass, belowground biomass, dead wood, litter, and sometimes soil carbon.

The project scenario tracks how these pools change over time under the improved management plan. For example, extending harvest rotations keeps more large-diameter trees standing, increasing aboveground biomass. Reducing road density and directional felling in reduced-impact logging retains more residual biomass and avoids soil disturbance.

Monitoring happens through periodic re-measurement of permanent sample plots, often supplemented by remote sensing (LiDAR, satellite imagery) to detect disturbances and verify standing volume between field visits. Third-party verifiers audit the calculations, check that management plans are being followed, and confirm that no unplanned harvesting or natural disturbances (fire, pests) have reversed gains. Only after verification are credits issued on the registry.

How IFM Credits Are Issued and Verified

The crediting cycle begins with a Project Design Document (PDD) that lays out the baseline, project activities, carbon accounting methods, monitoring plan, and risk mitigation measures. An accredited validation body reviews the PDD against the chosen methodology and approves the project design.

Once implementation starts, the project enters a monitoring period, typically five to ten years. At the end of each period, the project prepares a monitoring report with updated inventory data and carbon calculations. An independent verification body audits the report, confirms that the claimed emissions reductions or removals occurred, and issues a verification statement. The registry (Verra, ACR, Climate Action Reserve) then issues credits corresponding to the verified tonnes.

Importantly, IFM credits can be labelled as reductions or removals depending on the methodology and the nature of the management change. Credits from avoided harvest (keeping carbon that would have been released) are generally classed as reductions, while credits from incremental growth beyond a stable baseline may qualify as removals. This labelling matters for buyers building portfolios that align with SBTi removal mandates or Oxford Principles guidance.

Types of IFM Practices

Extended Rotation Harvesting

Extended rotation means delaying the age at which trees are cut beyond the typical commercial rotation. For example, a forest managed on a 40-year pulpwood rotation might shift to an 80-year sawtimber rotation under an IFM project. Longer rotations keep more biomass standing, allow trees to reach larger sizes, and increase average carbon stocks across the landscape.

This practice is common in temperate forests where economic models normally favour shorter rotations for faster cash flow. Carbon revenue can make longer rotations financially viable, offsetting the opportunity cost of delayed harvest. Extended rotations also improve habitat structure for species that depend on older forest conditions and can enhance watershed protection by maintaining continuous canopy cover.

Reduced Impact Logging

Reduced-impact logging (RIL) minimizes collateral damage during harvest operations. Techniques include directional felling to avoid damaging neighbouring trees, planned skid trails to reduce soil compaction, and lower road density to preserve more intact forest. The result is that more residual biomass is left standing, and regeneration happens faster because soil and seedling banks are less disturbed.

RIL is widely used in tropical IFM projects but also applies in temperate settings. While harvest still occurs, the intensity and ecological footprint are significantly lower than conventional logging. This practice delivers carbon benefits by conserving residual trees and dead wood pools, and it supports co-benefits like soil health, water quality, and biodiversity.

Forest Conservation Easements and Set-Asides

Conservation easements are legally binding agreements that restrict future land use, often permanently or for 99+ years. In the IFM context, a landowner may place a conservation easement on their property that limits harvest intensity, prohibits conversion to agriculture, or sets aside sensitive areas as no-cut reserves. The easement locks in higher carbon stocks over the long term and provides strong assurance of permanence.

These projects are often developed in partnership with conservation NGOs or land trusts and may layer public funding (grants, tax incentives) with carbon revenue. Easements are especially attractive for buyers seeking long-term permanence and clear legal protections, and they often carry co-benefits such as public access, wildlife corridors, and watershed conservation.

Natural Regeneration and Enrichment Planting

Some IFM projects improve stocking density and species composition within existing forests by encouraging natural regeneration or planting native species to fill gaps. This differs from afforestation because the land was already forest, but degraded or under-stocked due to past poor management. Enrichment planting accelerates carbon accumulation and improves forest resilience by increasing species diversity and structural complexity.

This practice is common in tropical regions where selective logging has left gaps, but it also applies in temperate forests recovering from fire or pest damage. The key distinction from ARR is that the baseline is an existing forest, and the project intervention speeds up recovery and increases future carbon stocks above what natural succession would deliver alone.

What Makes a High Quality IFM Carbon Credit

Additionality in IFM Projects

Additionality is the requirement that the carbon benefits would not have occurred without the project and its carbon revenue. For IFM, this means proving that the landowner would realistically have harvested more aggressively under business-as-usual, and that carbon finance changed that decision.

Red flags include baselines that assume clear-cuts where historical practice was selective logging, or where legal regulations already constrain harvest. For example, if local forest practice acts already require extended rotations or if the landowner's own management plans documented lighter cutting before the project started, additionality is questionable. High-quality projects provide transparent evidence of historical harvest rates, financial analysis showing carbon revenue was necessary to make conservation viable, and documentation of legal and market barriers to the lighter management regime.

Independent analyses have found that many legacy U.S. IFM projects struggled to demonstrate additionality, with minimal proof that management truly changed. Next-generation methodologies now require project-specific financial and legal additionality tests, dynamic baseline updates, and conservative common-practice benchmarks to reduce this risk.

Permanence and the Role of Buffer Pools

Permanence is the assurance that carbon stays stored for the long term, typically 100 years. Forests face reversal risks from wildfire, pests, storms, illegal logging, or future policy changes that could release stored carbon. IFM projects manage permanence through buffer pools and on-site risk mitigation.

Buffer pools are reserves of credits withheld from sale and held by the registry to cover future reversals. If a project suffers a fire that releases carbon, credits are retired from the buffer to compensate. However, research has shown that some buffer pools are severely undercapitalised, especially as wildfire risk increases under climate change. In California's compliance programme, cumulative wildfire reversals have consumed most of the wildfire component of the buffer, and the pool shrank in net terms during 2023 and 2024.

Buyers should ask to see project-specific risk ratings, the size of buffer contributions relative to historical disturbance rates in the region, and evidence of on-site risk reduction measures such as fuel management, pest monitoring, and legal protections. Strong permanence design includes diversification across geographies, conservative risk modelling, and mechanisms to top up buffers if losses exceed projections.

Conservative Baselines and Leakage Accounting

Conservative baselines are non-negotiable for high-quality IFM. Over-optimistic harvest scenarios have been the main driver of over-crediting in legacy projects. Buyers should scrutinise baseline sections of the Project Design Document and verification reports, comparing planned harvest volumes with historical practice, regional averages from national forest inventories, and legal or market constraints.

Next-generation methodologies address this by using dynamic matched baselines. For example, Verra's VM0045 matches project forests with similar non-project forests in the national inventory and tracks how those control forests are harvested over time, updating the baseline each reporting period. This reduces adverse selection and ensures the baseline reflects real-world trends rather than hypothetical maximums.

Leakage occurs when reduced harvest at the project site simply shifts logging to other forests, negating the climate benefit. IFM projects must estimate leakage, typically by applying a percentage discount (e.g., 10-20%) or by monitoring harvest activity in comparable forests owned by the same entity or in the same region. High leakage is a particular risk when the project covers only a small fraction of a landowner's total holdings or when timber markets are tight. Transparent leakage analysis and conservative deductions are hallmarks of rigorous projects.

Independent Third Party Verification and Ratings

All credible IFM projects undergo validation and verification by accredited third-party auditors who confirm that methods, measurements, and claims meet the registry's standards. However, registry verification alone is not sufficient. External quality ratings from firms like BeZero, Sylvera, and Calyx Global provide an additional layer of scrutiny, scoring projects on additionality, permanence, leakage, and over-crediting risk.

In 2025, BeZero published a review of U.S. IFM ratings showing several downgrades due to unrealistic baselines, but also highlighting that next-generation projects with robust design can achieve higher ratings. Buyers should triangulate multiple signals: registry approval, independent ratings, and integrated due diligence frameworks like Senken's Sustainability Integrity Index, which evaluates IFM projects across 600+ data points including carbon impact, beyond-carbon co-benefits, reporting quality, and compliance with emerging standards.

IFM Methodologies and Certification Standards

Verra VM0045 With Dynamic Matched Baselines

Verra's VM0045 methodology, approved for ICVCM's Core Carbon Principles label in August 2025, represents a step change in IFM integrity. VM0045 uses dynamic matched baselines drawn from national forest inventory data (currently U.S. Forest Inventory and Analysis, or FIA). Project forests are matched with similar non-project control plots based on location, species, age, and site characteristics. Harvest activity in the control plots provides the baseline, and this baseline is updated every reporting period to reflect actual market and regulatory conditions.

This approach directly addresses baseline inflation by anchoring the counterfactual in observed real-world data rather than theoretical regional averages. VM0045 also separates reductions (avoided emissions from reduced harvest) from removals (carbon sequestered through incremental growth), enabling clearer labelling for buyers building SBTi-aligned portfolios.

The first CCP-labelled IFM credits under VM0045 were issued in December 2025 to the Family Forest Carbon Program, a collaboration between the American Forest Foundation and The Nature Conservancy aggregating small private forest owners in the Central Appalachian region. This signals that high-integrity, scalable IFM supply is beginning to enter the market, but volumes are still limited.

ACR Improved Forest Management Methodology

The American Carbon Registry's IFM on Non-Federal U.S. Forestlands methodology v2.1, updated in July 2024 and CCP-approved in August 2025, is the other major next-generation IFM framework. ACR IFM v2.1 introduces a dynamic baseline evaluation tool that re-assesses the harvest baseline each reporting period using updated market data, landowner financial models, and legal constraints.

The methodology also includes a harvest intensity constraint: project harvests must remain below a defined threshold to qualify for crediting, preventing projects from claiming credits for modest reductions while still logging heavily. ACR IFM v2.1 projects can label credits as reductions or removals based on the nature of the carbon benefit, aligning with buyer demand for clearly categorised mitigation outcomes.

Major corporate offtakes have been structured around ACR IFM v2.1 projects. Microsoft's 10-year agreement with Anew Climate and Aurora Sustainable Lands, announced in June 2025, will deliver 4.8 million nature-based removal credits from next-generation IFM projects registered under ACR. The Conservation Fund's Hodag Forest Project was the first to receive CCP-labelled credits under ACR IFM v2.1, issuing nearly 190,000 credits in September 2025.

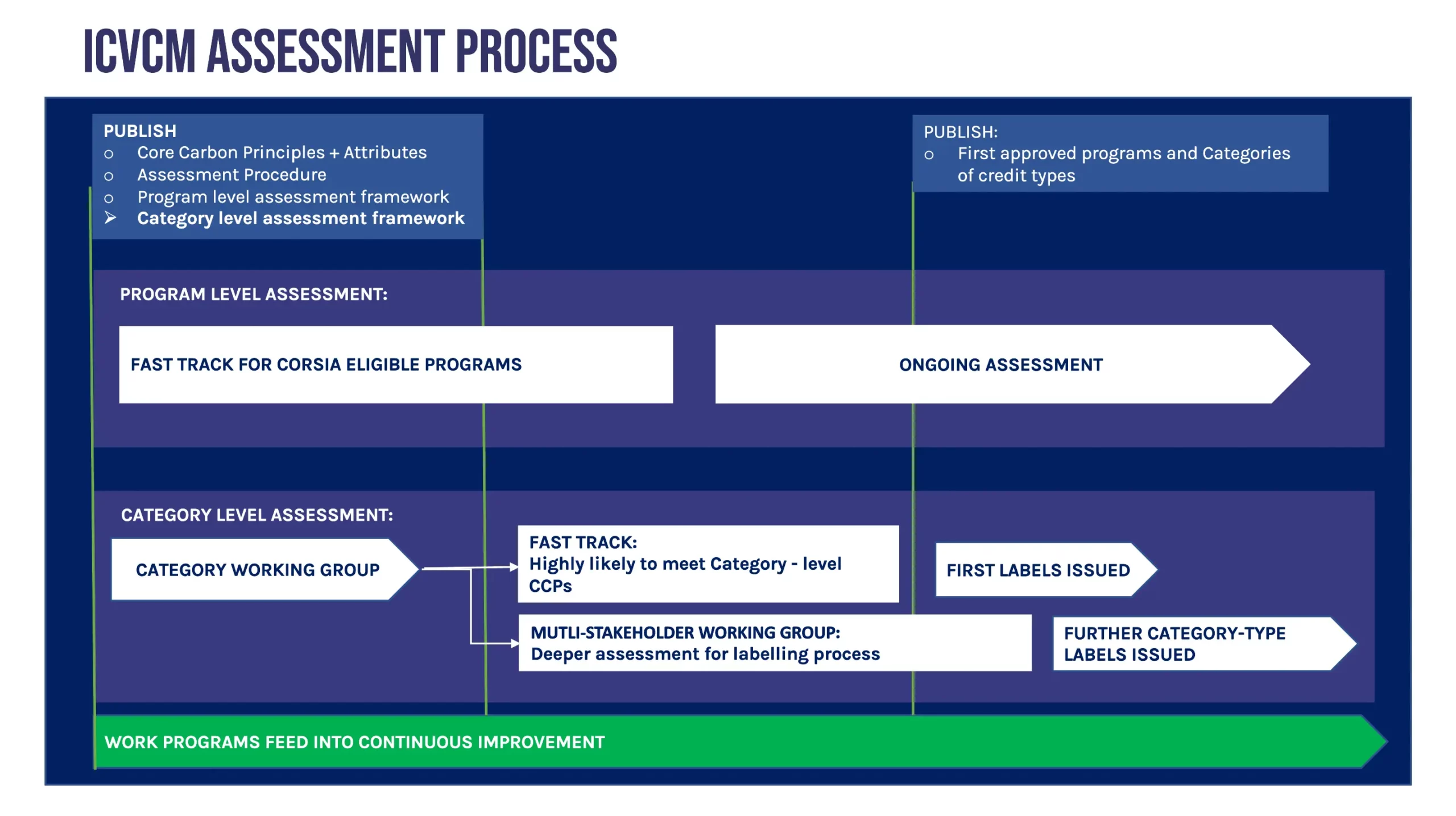

ICVCM Core Carbon Principles and CCP Labels

The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM) has approved both VM0045 and ACR IFM v2.1 as meeting its Core Carbon Principles, a set of integrity criteria covering additionality, robust quantification, permanence, no double counting, and sustainable development. CCP approval at the methodology level signals that projects using these methods meet minimum high-integrity standards, but it does not guarantee quality at the individual project level.

Buyers should understand that CCP labels are one filter in a multi-layer due diligence process. Methodology choice is a strong positive signal, but project-specific factors like baseline conservativeness, buffer pool design, leakage risk, and governance quality still require assessment. Senken's Sustainability Integrity Index automates much of this project-level screening, ensuring that only IFM credits from CCP-aligned methodologies and passing rigorous project-specific checks enter client portfolios.

How IFM Compares to REDD+ and Afforestation Credits

IFM vs. REDD+ Avoided Deforestation

REDD+ projects protect forests facing imminent threats of conversion to agriculture, logging, or development. The baseline in REDD+ is deforestation or severe degradation, and the project intervention prevents that loss. IFM, by contrast, assumes the land will remain forest under both scenarios, with the difference being harvest intensity and average carbon stocks.

Risk profiles differ significantly. REDD+ projects face high baseline and leakage risks because proving the forest was truly threatened, and that protection didn't just shift deforestation elsewhere, is difficult. Multiple investigative analyses over the past three years have found substantial over-crediting in REDD+, leading many European buyers to reduce REDD+ exposure. IFM avoids some of these issues because the counterfactual is not "forest vs. no forest" but "more harvest vs. less harvest," which is easier to document and verify when methodologies are robust.

However, IFM carries its own permanence and additionality challenges. Co-benefits also differ: REDD+ projects are often in biodiversity hotspots with high Indigenous community involvement, while U.S. IFM may offer fewer social co-benefits but stronger legal permanence through conservation easements. Buyers should choose based on risk tolerance, portfolio diversification goals, and stakeholder narrative priorities.

IFM vs. Afforestation and Reforestation Projects

Afforestation and reforestation (ARR) create new forests on land that was not recently forested. ARR delivers clear additionality (the forest would not exist without the project) and is unambiguously a carbon removal. However, ARR projects can take decades to accumulate significant carbon, face high mortality risk in early years, and often require ongoing maintenance and replanting.

IFM can deliver earlier volumes because it starts from an existing mature forest stock and captures incremental gains from improved management. Permanence risks differ: ARR faces establishment risk, while IFM faces harvest pressure and natural disturbance. IFM's additionality is harder to prove because the baseline forest already exists, whereas ARR's additionality is more straightforward.

From a portfolio perspective, many buyers combine IFM and ARR to balance near-term volume (IFM) with long-term removal growth (ARR). IFM is often more cost-effective per tonne in the near term, while ARR may offer stronger co-benefits and clearer removal labelling. An Oxford-aligned portfolio might include high-quality IFM alongside ARR and engineered removals, with the share of durable tech removals increasing over time as required by SBTi Net-Zero trajectories.

Co-Benefits of IFM Projects Beyond Carbon

Biodiversity and Wildlife Habitat

Extended rotations, reduced-impact logging, and set-asides preserve forest structure that is essential for biodiversity. Older forests support more complex habitat: standing dead wood, canopy gaps, diverse understory, and large-diameter trees that provide nesting sites and food resources. IFM projects in the U.S. Pacific Northwest, for example, maintain habitat for threatened species like the northern spotted owl, while tropical IFM protects refuges for primates, big cats, and endemic bird species.

For buyers building nature-positive strategies under frameworks like TNFD, IFM's biodiversity co-benefits can be a strong narrative element. However, these outcomes must be monitored and documented. High-quality IFM projects track biodiversity indicators (species counts, habitat connectivity, presence of keystone species) and report them transparently in verification documents. This allows corporates to include biodiversity impacts in CSRD disclosures and stakeholder communications without falling into greenwashing.

Watershed Protection and Soil Health

Maintaining continuous forest cover stabilises soils, reduces erosion, and regulates water flow. IFM projects that avoid clear-cutting or reduce road density protect water quality in streams and rivers that supply downstream communities. Forests filter sediments, moderate water temperature, and recharge groundwater, services that are increasingly material to companies with water-related KPIs or supply chain dependencies on clean water.

Soil carbon is also often included in IFM accounting. Reduced soil disturbance from lighter harvesting preserves soil organic matter, which supports long-term site productivity and carbon storage. For companies with agricultural supply chains or water stewardship commitments, IFM projects that deliver documented watershed and soil benefits can support multiple ESG goals within a single investment.

Community Livelihoods and Indigenous Rights

Many IFM projects involve community or Indigenous landowners who earn revenue from carbon while retaining ownership and management control. Timber revenues continue under the improved management regime (albeit at lower volumes), and carbon payments provide a diversified income stream that reduces economic pressure to over-harvest.

Projects on Indigenous lands often require Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) and include benefit-sharing agreements. For European buyers navigating CSRD's social and governance requirements, these documented community engagement processes and livelihood benefits strengthen the defensibility of carbon credit use. However, buyers must verify that FPIC and benefit-sharing are real and ongoing, not one-time checkbox exercises. Monitoring reports, independent audits, and third-party certifications like the Climate, Community & Biodiversity (CCB) standard provide evidence that social co-benefits are being delivered.

How to Evaluate IFM Projects Before Purchasing

1. Confirm Methodology, Registry, and Any CCP Labels

Start by identifying the exact methodology (e.g., Verra VM0045 v1.2, ACR IFM v2.1) and the registry where credits are issued. Check whether the methodology has been approved by ICVCM for the Core Carbon Principles label. CCP approval is a strong positive signal but not a guarantee of project quality.

Non-CCP methodologies are not automatically disqualified, but they warrant closer scrutiny. Older IFM methodologies from the 2010s (e.g., CAR's early U.S. Forest Protocol versions, Verra VM0010 pre-2024 revisions) lack the dynamic baseline and harvest intensity safeguards of next-generation approaches. If the project uses a legacy method, ask why, and demand additional evidence of baseline conservativeness and additionality.

2. Assess Baseline Conservativeness and Harvest Assumptions

Request the Project Design Document and the most recent verification report. Read the baseline section carefully. Compare the assumed business-as-usual harvest volumes and rotation ages with the landowner's historical harvest records, regional forest practice norms, and any legal or market constraints.

Red flags include sudden switches from selective logging to hypothetical clear-cuts just before the project start date, baselines that ignore binding legal restrictions (e.g., endangered species habitat protections), or a lack of financial analysis showing that carbon revenue was necessary to change management. Positive signals include matched-plot baselines using national inventory data, conservative assumptions that align with regional averages, and transparent updates to the baseline each reporting period.

3. Review Permanence Measures and Buffer Pool Allocations

Examine the project's risk rating for fire, pests, disease, illegal harvest, and policy change. Check how much of each credit vintage was contributed to the buffer pool and compare that rate with historical disturbance frequencies in the region. Ask what happens if a major reversal occurs: does the buffer pool have sufficient depth, and are there mechanisms to replenish it?

Look for on-the-ground risk mitigation: fuel reduction treatments in fire-prone areas, pest monitoring and rapid response plans, legal easements or long-term contracts that lock in conservation beyond the crediting period. Projects with strong permanence design will document these measures in detail and report on monitoring outcomes in every verification cycle.

4. Verify Independent Auditing and External Ratings

Confirm that validation and verification were conducted by accredited third-party auditors with forest carbon expertise. Check the auditor's name and accreditation status on the registry's website. Then layer on external ratings: does the project have a rating from BeZero, Sylvera, or Calyx Global, and what is the score?

Compare ratings across agencies if available. Ratings may differ due to different methodologies, but consistent high marks across multiple raters is a positive signal. Conversely, a low rating or recent downgrade is a red flag. Finally, consider integrated assessments like Senken's Sustainability Integrity Index, which combine registry verification, external ratings, and proprietary due diligence across 600+ data points to give a holistic quality score.

5. Request and Review Co-Benefit and Stakeholder Documentation

Ask for evidence of biodiversity monitoring, social impact assessments, FPIC documentation (if applicable), and mapping to UN Sustainable Development Goals. High-quality projects will provide biodiversity survey reports, community engagement logs, benefit-sharing agreements, and third-party social certifications (e.g., CCB, SD VISta).

This documentation serves two purposes: it strengthens your internal narrative around why IFM is part of your strategy, and it provides audit-ready evidence for CSRD and Green Claims compliance. If a project cannot produce clear co-benefit evidence, treat it as a signal that governance and monitoring may be weak across the board.

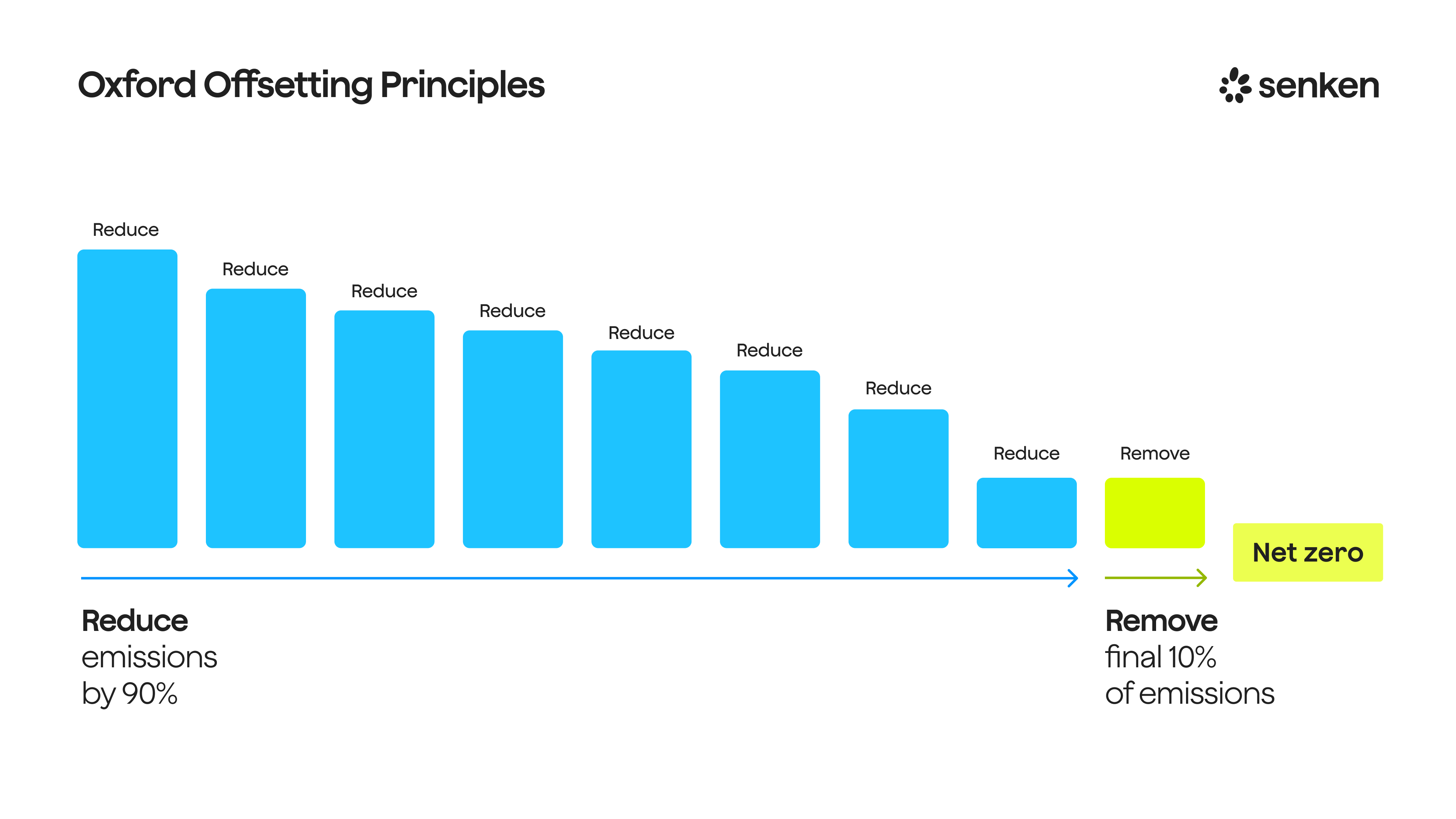

How IFM Credits Fit Into a CSRD Ready Carbon Portfolio

Positioning IFM as Beyond Value Chain Mitigation

Under current SBTi guidance, IFM credits cannot be used to meet near-term science-based reduction targets. However, they can play a clearly defined role as beyond value chain mitigation (BVCM): voluntary climate action that goes beyond a company's own footprint while the company aggressively decarbonises operations.

In practice, this means disclosing IFM use separately from your Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions reductions, framing it as part of a holistic climate strategy rather than an offset. The Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI) provides claims guidance for BVCM, and SBTi's draft Net-Zero Standard 2.0 (expected final release in 2025) will clarify how removals like IFM can support long-term neutralisation of residual emissions after 90%+ reductions have been achieved.

For CSRD reporting, disclose the volume, type, vintage, and methodology of IFM credits purchased, the verification standard, and the role they play in your climate strategy. Avoid blanket "carbon neutral" claims; instead, use language like "neutralising residual Scope 1 and 2 emissions through high-integrity forest carbon removals validated to [standard] as part of beyond value chain mitigation."

Allocating IFM Within an Oxford-Aligned Portfolio

The Oxford Principles for Net Zero Aligned Carbon Offsetting recommend that corporates prioritise internal reductions, use high-quality removals for residual emissions, and shift over time from nature-based to long-duration engineered removals. IFM can fit into this framework in the near and medium term, particularly when credits are clearly labelled as removals and meet CCP standards.

A typical Oxford-aligned portfolio might include 50-70% nature-based removals (IFM, ARR, soil carbon) and 30-50% tech-based removals (biochar, enhanced weathering, DAC) in the early years, shifting to 70%+ tech-based by 2040. Within the nature-based share, IFM offers advantages: it can deliver volume today, often at lower cost per tonne than engineered solutions, and with strong co-benefits.

Senken's approach is to blend high-quality IFM (CCP-labelled, rigorously vetted) with other removal types to balance cost, volume, co-benefits, and durability. This allows clients like Deutsche Telekom and Vodafone to meet near-term BVCM needs while building toward a higher-permanence portfolio over time. IFM is not a permanent solution but a pragmatic bridge in a strategy that ramps up durable removals as supply and budget allow.

What Auditors, Regulators, and Stakeholders Will Expect

Auditors conducting CSRD assurance or financial audits with ESG components will ask for traceability: proof that credits were purchased, retired in your name, and correspond to real, verified emissions reductions or removals. They will scrutinise methodology, registry records, and any claims made in public reports or marketing.

Regulators under the EU Green Claims Directive will require substantiation that environmental claims are accurate, specific, and evidence-based. Blanket claims like "carbon neutral" are likely prohibited unless you can demonstrate outstanding environmental performance across the product lifecycle, not just through credits. Instead, claims should specify "residual emissions neutralised through verified forest carbon removals" and link to transparent evidence packs.

Stakeholders, including investors, NGOs, and customers, increasingly expect companies to show not just that they bought credits, but that the credits are high-quality and part of a science-aligned strategy. Providing access to project-level scorecards, independent ratings, and clear portfolio composition (e.g., "30% IFM removals, 40% ARR, 30% biochar") builds trust and pre-empts greenwashing accusations. Senken's platform generates these evidence packs automatically, linking each retired credit to its Sustainability Integrity Index score, methodology documentation, and co-benefit reports.

.svg)