Residual emissions are the greenhouse gas emissions that remain at the net-zero year after all technically and economically feasible mitigation efforts, which must be permanently neutralised with carbon dioxide removal. For sustainability managers in large DACH companies, this definition has shifted from academic terminology to a board-level governance issue. IPCC 1.5 °C pathways show that energy system CO₂ must fall by 87–97% by 2050, leaving only 3–13% of 2020 levels as truly residual. Meanwhile, SBTi now expects most sectors to achieve 90%+ gross reductions, and EU regulation – CSRD/ESRS E1, the Green Claims Directive, IFRS S2 – is tightening the rules on what you can call "unavoidable" and how you substantiate climate claims with carbon credits. The gap between theory and practice is where risk lives: misclassify avoidable emissions as residual, and you face audit failures, greenwashing allegations, and wasted capital on low-quality offsets. This article is your practical playbook for defining, quantifying, governing, and balancing residual emissions inside a credible net-zero strategy.

1. What Are Residual Emissions in a Corporate Net-Zero Strategy?

Residual emissions are those emissions still released into the atmosphere when global net zero is reached, remaining after all mitigation and avoidance efforts, and must be counterbalanced by carbon dioxide removal (CDR).

This definition matters because it sets a clear line between what you actively reduce and what you ultimately need to neutralize. In practice, residual emissions are not a synonym for "expensive to cut" or "inconvenient to tackle." They represent the genuinely stubborn tail of your footprint after you've exhausted all technically and economically feasible mitigation options at your net-zero target year.

The difference between residual, hard-to-abate, and unavoidable emissions

These terms often get used interchangeably, but they mean different things:

- Hard-to-abate emissions are those from sectors or processes where decarbonization is technically or economically challenging today, such as cement clinker production, steel blast furnaces, long-haul aviation, and certain agricultural processes like enteric fermentation and rice cultivation.

- Unavoidable emissions is a looser term sometimes used for emissions that are difficult to eliminate with current technology, but it lacks a precise, standards-based definition and risks becoming a catch-all excuse.

- Residual emissions are the time-specific subset that remains at the point you claim net zero, after full application of the mitigation hierarchy.

Think of it this way: today's hard-to-abate emissions may not be residual in 2040 if breakthrough technologies or cost curves shift. In modelled pathways limiting warming to 1.5 °C, residual non-CO₂ emissions amount to about 8 GtCO₂-eq per year at net zero (range 5–11 GtCO₂-eq), and net energy system CO₂ emissions fall by 87–97% between 2020 and 2050, leaving only 3–13% of 2020 levels as residual. For your company, this translates into a simple expectation: what you call residual today must be periodically re-tested as technology, regulation, and economics evolve.

2. Why Residual Emissions Are Now a Governance and Compliance Issue in DACH

Misclassifying avoidable emissions as residual creates real legal and reputational risk. If you label emissions as "unavoidable" too early and offset them with low-quality credits, you face greenwashing accusations, regulatory penalties, and stakeholder backlash. The bar has shifted dramatically in the past 18 months.

The regulatory tightening

Three major EU frameworks now directly affect how you define and disclose residual emissions:

- CSRD/ESRS E1 requires you to set and report gross GHG reduction targets, document the mix of decarbonization levers (CapEx, OpEx, emissions reductions by source), and exclude carbon credits from target achievement. You must also describe technology assumptions and update your base year every five years post-2030.

- IFRS S2 mandates that if you set a net GHG emissions target, you must also disclose a gross emissions target and describe your planned use of carbon credits to offset residual emissions, including type, quantity, and permanence.

- The EU Green Claims Directive requires that explicit environmental claims such as "net zero" or "carbon neutral" be substantiated by transparent, science-based methods, specify the share of emissions offset, and undergo independent verification.

Together, these rules mean that you can no longer quietly treat a large chunk of your footprint as "residual" and buy your way to a net-zero claim with cheap avoidance credits. Auditors, investors, and regulators now expect to see evidence that you applied the mitigation hierarchy first and that any carbon credits used to balance residuals meet high integrity standards.

The cost of getting it wrong

The evidence is stark: more than 68% of DAX40 companies that purchased carbon credits ended up with portfolios including projects delivering no real climate impact, and 84% of carbon credits on the market are considered high-risk. Companies like Deutsche Umwelthilfe have already sued firms over "climate neutral" labels based on low-quality offsets. Under the Green Claims Directive, companies found guilty can face fines of at least 4% of annual turnover. This is no longer a theoretical risk.

3. Defining Residual Emissions Inside Your Company: A Simple 4-Step Framework

Most DACH sustainability teams struggle not with the concept of residual emissions, but with operationalizing it. Here's a pragmatic process you can run internally within the next quarter:

Step 1: Map major emission sources by scope and process

Start with your Scope 1, 2, and 3 inventory and break it down by major source or business unit. Don't stop at the scope level; go one layer deeper to identify specific processes (e.g., natural gas combustion in boilers, refrigerant leakage, purchased electricity, business travel by air, upstream transport and distribution).

Step 2: Apply the mitigation hierarchy and assess technical/economic feasibility

For each source, ask three questions:

- Can we avoid this emission entirely (e.g., eliminate the activity, shift to a different business model)?

- Can we reduce it through efficiency, process optimization, or technology switching (e.g., electrification, hydrogen, renewables)?

- Can we replace it with a lower-carbon alternative (e.g., sustainable aviation fuel, green cement, circular materials)?

Layer on a basic marginal abatement cost analysis: what does it cost per tonne to reduce this emission source by 50%, 80%, 90%, or 95% by 2030, 2040, and 2050? Consider not just direct costs, but also supply chain maturity, regulatory risk, and technology readiness.

Step 3: Classify each source

Now categorize:

- Avoidable now: Mitigation is technically feasible and economically justified today or in the near term (e.g., switching to renewable electricity, improving building insulation).

- Hard-to-abate but declining: Reduction is expensive or technically challenging today, but expected to become feasible by 2030–2040 as technologies scale (e.g., green hydrogen for industrial heat, electric long-haul trucks).

- Truly residual at target year: After all realistic mitigation, a small emission remains in 2050 due to fundamental technical or economic constraints (e.g., process emissions from certain chemical reactions, residual methane from livestock in agriculture-heavy value chains).

Step 4: Document your working definition and set review triggers

Translate this into an internal policy. A simple decision tree might look like this:

- Is a technical solution available at commercial scale? If yes, not residual.

- Is the abatement cost below €200/tCO₂ (or your internal carbon price ceiling)? If yes, not residual.

- Is there a credible supplier engagement or R&D pilot underway? If yes, classify as "hard-to-abate under review" rather than residual.

- Have we tested this classification in the last five years? If no, reclassify.

Set a mandatory review every five years aligned with SBTi target recalibration and ESRS E1 updates. What you call residual in 2025 should be re-challenged in 2030, 2035, and so on.

4. Turning Definitions into Numbers: Building a Residual Emissions Baseline and Budget

Once you have a qualitative framework, you need to translate it into numbers. This is where most companies stall.

Project decarbonization pathways for key sources

Take each major emission source and model a realistic reduction trajectory to 2050. Use sector benchmarks where available. SBTi's cross-sector pathway requires at least 90% reduction by 2050 for most companies, setting the residual emissions level at a maximum of 10% of baseline. Sector-specific targets allow different residual shares: agriculture 72% reduction (28% residual), cement 94% reduction (6% residual), iron & steel 91% reduction (9% residual), power 97% reduction (3% residual).

For a DACH industrial company with a 2020 baseline of 500,000 tCO₂e, applying a 90% reduction pathway means your residual budget in 2050 should not exceed 50,000 tCO₂e. If you're in cement or steel, adjust using the sector-specific pathway; if you're a bank or telco, you should be aiming for the stricter cross-sector threshold or lower.

Build a residual emissions budget table

Create a simple internal table per major source:

Sum these across all sources to derive your total residual budget. If the total exceeds 10% of your baseline (or your sector-specific threshold), you need to go back and challenge your assumptions or accept that your net-zero target may not be SBTi-compatible.

Set interim checkpoints

Don't just set a 2050 residual budget. Establish interim ceilings for 2030 and 2040 to create accountability and force periodic reassessment. This also aligns with CSRD transition plan requirements and gives your CFO and risk function visibility into long-term carbon removal procurement needs.

A note of caution on over-reliance on future CDR

Analysis of national long-term strategies shows that countries often assume around 18% of current emissions as residual by 2050, banking heavily on future carbon removal supply. For corporates, this is risky: SBTi expects stricter thresholds, and carbon removal markets remain supply-constrained and expensive. Budget conservatively.

5. Who Owns Residual Emissions? Governance, Reviews and Disclosure

Residual emissions decisions sit at the intersection of sustainability, finance, risk, and operations. Without clear ownership and governance, they will be defined inconsistently and challenged in audits.

Recommended ownership model

For a large DACH company:

- Chief Sustainability Officer (CSO) and Climate Steering Committee: Own the residual emissions definition, budget, and review process. Set the policy, approve classifications, and escalate material changes to the board.

- Business units and operations: Own implementation of mitigation measures and provide bottom-up input on technical feasibility and costs.

- Finance and risk functions: Sign off on key assumptions, carbon credit usage, and budget envelopes. Integrate residual emissions into internal carbon pricing and CapEx/OpEx decisions.

- Legal and compliance: Ensure residual emissions treatment is consistent with CSRD, IFRS S2, and Green Claims Directive requirements and embedded in supplier contracts and disclosures.

Governance checklist

To make this real, ensure:

- Residual emissions policy is approved by the board or executive committee.

- Documented criteria and decision rights are in place (who can classify a source as residual? who approves exceptions?).

- Integration into internal carbon pricing: residual emissions that must be offset should carry a higher shadow price than emissions targeted for reduction.

- Mandatory 5-year review cycle aligned with SBTi target recalibration and ESRS E1 updates.

- Residual-related assumptions, decarbonization levers, and planned carbon credit use are disclosed in CSRD reports and discussed with auditors.

What auditors and investors will look for

Expect scrutiny on:

- Evidence of mitigation hierarchy application: Can you show that you explored avoidance, reduction, and replacement options before classifying emissions as residual?

- Documentation of technology and cost assumptions: Why do you believe a given source will still be residual in 2040? What technology developments would invalidate that assumption?

- Carbon credit quality and procurement strategy: If you plan to use credits to neutralize residuals, what standards do they meet? Are they removal-based, and what is their permanence?

- Consistency with public commitments: Does your residual budget align with your SBTi target and public net-zero claims?

Weak governance here creates audit findings, investor downgrades, and reputational exposure.

6. Balancing Residual Emissions with High-Integrity Carbon Removal

Once you've defined and quantified your residuals, the final step is matching them with high-quality carbon removal. This is where rigorous due diligence separates credible net-zero strategies from greenwashing.

Why only carbon removal credits should neutralize residuals

At the point of net zero, residual emissions must be counterbalanced by carbon dioxide removal (CDR). Avoidance credits (e.g., renewable energy, cookstoves) do not remove CO₂ from the atmosphere; they prevent emissions elsewhere. Using them to offset residuals undermines the science of net zero and exposes you to regulatory and reputational risk. SBTi, WRI, and IPCC all agree: residuals must be neutralized with permanent removals.

Portfolio principles for DACH corporates

Build a diversified CDR portfolio:

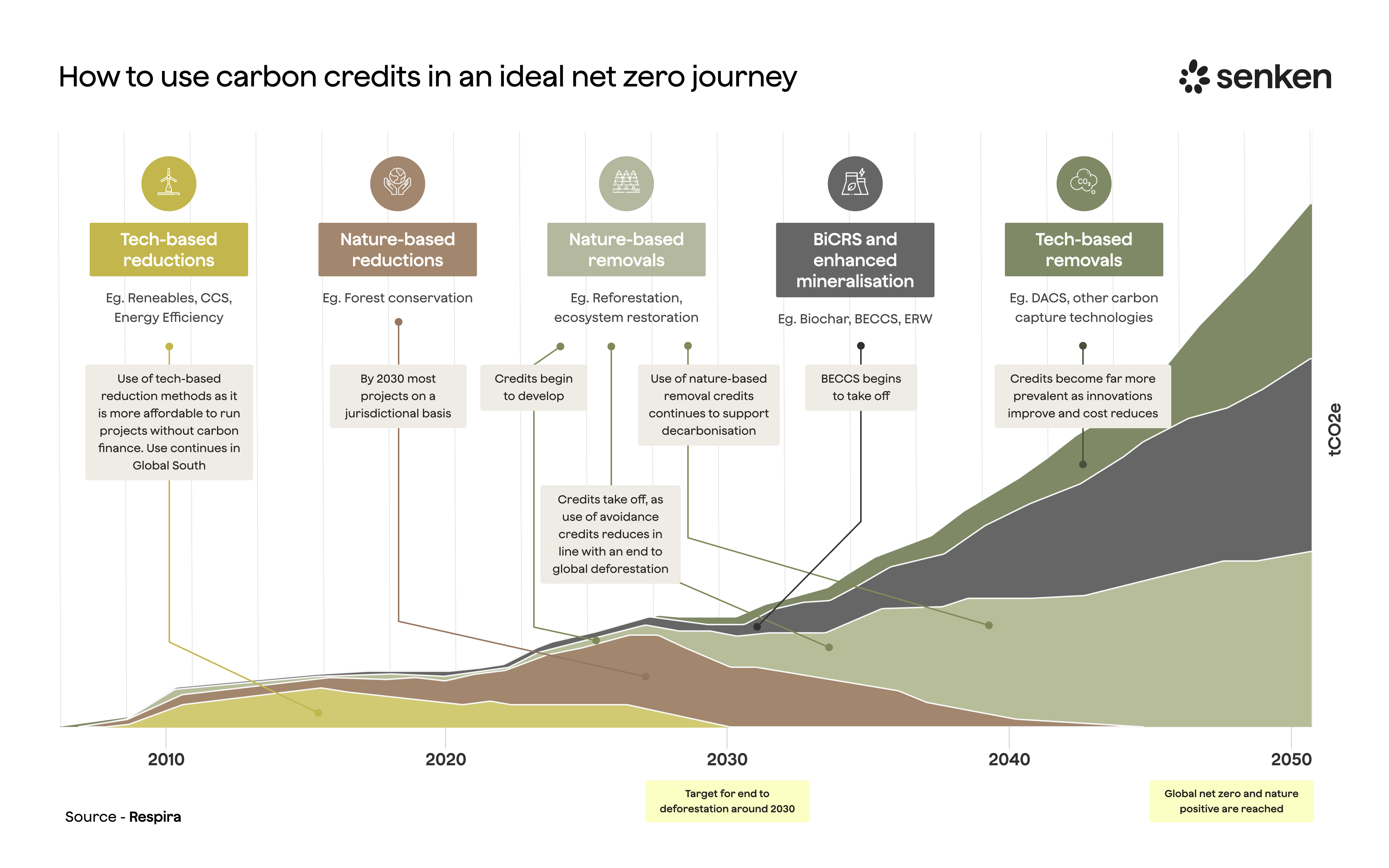

- Blend near-term nature-based removals with longer-lived technological removals: Start with forestry, biochar, or enhanced weathering to meet near-term needs and manage costs, then phase in more durable options like direct air capture (DAC) as supply scales and your residual budget tightens.

- Increase durability over time: In 2030, conventional removals (100+ years permanence) may dominate your portfolio; by 2040–2050, shift toward novel removals (1000+ years) to align with the long-term nature of residual emissions.

- Phase out low-integrity methodologies: Avoid renewable energy and cookstove credits entirely. Be cautious with REDD+ projects that have high reversal risk or weak additionality.

Translate residual budgets into procurement plans

If your 2050 residual budget is 50,000 tCO₂e per year, you need to procure at least that volume in high-quality carbon removal annually from 2050 onward. Work backward: how do you scale procurement from today's levels to meet that need? What contracts, supplier relationships, and financing instruments do you need?

Set internal quality guardrails:

- Additionality: The removal would not have happened without the carbon finance.

- Permanence: Storage duration should match or exceed the atmospheric lifetime of CO₂ (ideally 100+ or 1000+ years).

- Robust MRV: Measurement, reporting, and verification must be transparent, third-party audited, and use credible methodologies.

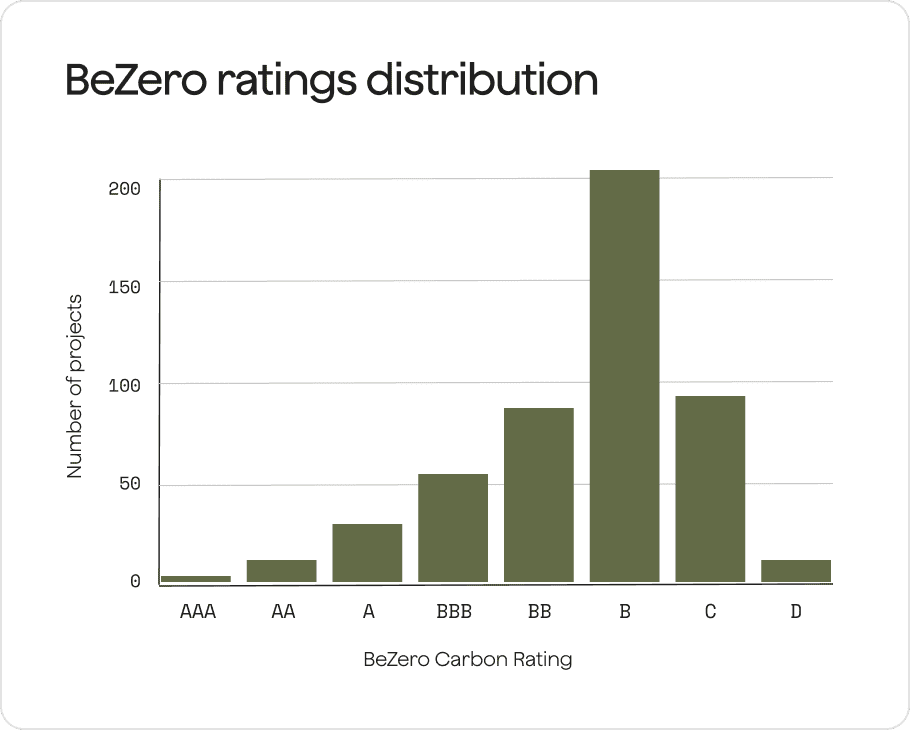

- Third-party verification: Credits should be verified by recognized registries (Verra, Gold Standard, Puro.earth) and, where possible, rated by independent agencies (BeZero, Sylvera).

- Alignment with emerging standards: Look for ICVCM Core Carbon Principles approval or Oxford Principles alignment.

How Senken de-risks this process

Selecting high-integrity carbon removal credits at scale is complex and risky. Senken's 600+ datapoint Sustainability Integrity Index provides the deep due diligence needed to separate genuine climate impact from greenwashing. Every project is assessed across five dimensions: project fundamentals, carbon impact (additionality, permanence, leakage), beyond-carbon co-benefits (social, environmental, governance), reporting processes (MRV), and compliance and reputation. Only projects that pass this rigorous screen enter client portfolios, ensuring your residual emissions are balanced with credits that will stand up to auditor scrutiny, regulatory review, and stakeholder challenge.

By linking your residual emissions budget directly to a procurement strategy grounded in transparent, data-driven quality criteria, you transform residual emissions from a theoretical concept into an audit-ready, high-impact implementation.

.svg)