What double counting means in carbon markets

Double counting in climate terms means counting a single quantity of mitigation outcomes for more than one mitigation purpose. In practice, this happens when the same emission reduction or removal gets claimed by multiple actors or toward multiple goals. Picture a forest conservation project in Indonesia: the host country counts the avoided emissions toward its Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC), while a European company buying credits from the same project claims them as offsets for "carbon neutral" products. That's double claiming, and it's one of the most common forms of double counting you'll encounter.

Why does this matter beyond the technical definition? Two reasons, and both directly affect your role.

First, double counting inflates global climate progress. When the same tonne of CO₂ is counted multiple times across national inventories and corporate claims, the world appears to be decarbonising faster than it actually is. ESRS E1 explicitly requires companies to avoid double counting of fuel consumption and GHG emissions between scopes , signaling that EU regulators now treat this as a core reporting integrity issue, not an accounting footnote.

Second, double counting creates direct corporate risk. Under CSRD, your sustainability report will undergo limited assurance (and soon reasonable assurance). Auditors will ask how you know your Scope 2 renewable energy claims don't overlap with grid emission factors, or whether the carbon credits you're retiring have already been claimed by someone else. More than 68% of DAX40 companies that purchased carbon credits ended up supporting projects with no real climate impact , and many are now facing scrutiny over their climate claims. Double counting doesn't just undermine your mitigation strategy; it exposes you to greenwashing allegations and enforcement actions that can reach 4% of annual turnover under the emerging Green Claims Directive.

The good news? Double counting is largely a governance and data problem, not an inherent flaw of carbon markets. With the right controls, you can design it out of your portfolio entirely.

Where double counting shows up in a corporate portfolio

The main mechanisms: double issuance, double use, double claiming

The UNFCCC technical framework breaks double counting into three core mechanisms, each of which maps to real instruments you're likely procuring or evaluating.

Double issuance occurs when more than one mitigation outcome unit is created for the same emission reduction or removal, either within the same registry or across multiple registries. Historically, this was a risk when CDM projects sought credits under both international and national schemes. The CDM Executive Board in April 2014 addressed risks of double issuance where CDM projects sought simultaneous issuance under national or private schemes , encouraging voluntary cancellation to prevent duplicate credits entering circulation. Today, robust registries like Verra, Gold Standard, and Climate Action Reserve use unique serial numbers to prevent this, but the risk persists in markets with weaker infrastructure or when developers operate across multiple jurisdictions without clear coordination.

Double use (often called double selling) describes a scenario where the same allowance or credit is used more than once toward achieving mitigation pledges , such as being transferred to another registry without proper cancellation or retirement. This can also happen when a credit is sold to one party but later claimed by another due to poor record-keeping or fraud. Verra's VCS registry assigns each Verified Carbon Unit (VCU) a permanent unique serial number, tracked from issuance to retirement, preventing double issuance or double retirement. The controls exist, but your procurement process must verify them.

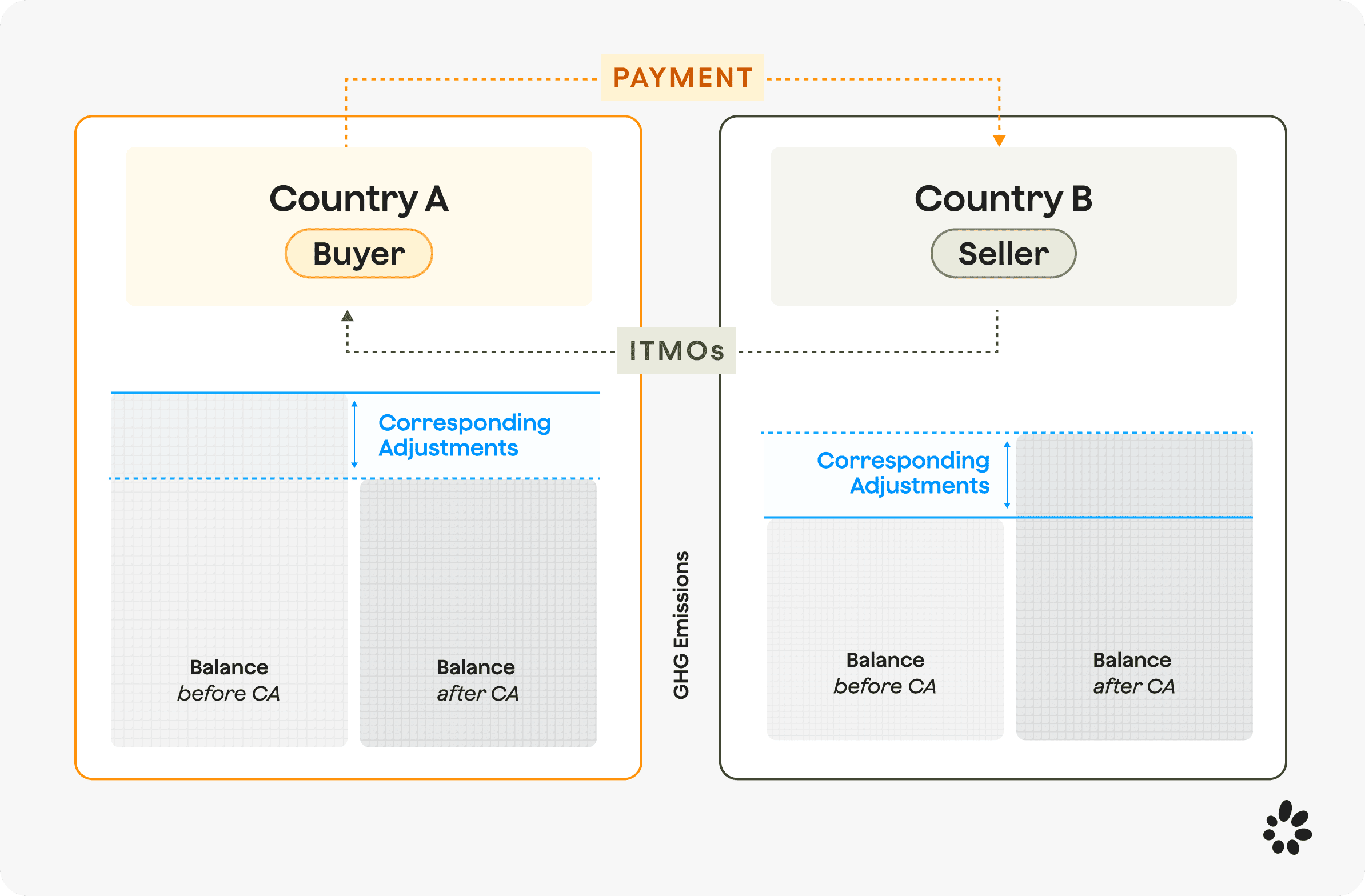

Double claiming is where things get complicated for corporates. Double claiming occurs when the same emission reduction is counted by two different parties , typically when a host country counts a reduction toward its NDC while a company buying credits from that project also claims it. This is the frontline issue under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, and it's why corresponding adjustments have become a mandatory part of high-integrity credit discussions.

High-risk hotspots: energy instruments, carbon credits and supply chains

Now let's translate those mechanisms into the instruments sitting in your portfolio or on your procurement shortlist.

Scope 2 renewable energy instruments are a major flashpoint. A study of China's Beijing, Shanghai and Tianjin ETSs found that PPAs and on-site renewable generation counted twice—zeroed out for corporate Scope 2 under market-based accounting while still included in grid emission factors—creating Scope 2 double counting risks. If you're buying Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs), Guarantees of Origin (GOs), or entering into Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs), the risk is that your market-based claim of zero emissions overlaps with a grid factor that hasn't been adjusted downward to reflect your contractual purchase. The GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance standardises accounting and mandates dual reporting (location-based and market-based) to prevent double counting of the same emissions. Yet implementation varies, and an Icelandic regulator report revealed energy-intensive companies claiming renewable electricity use without corresponding Guarantees of Origin, constituting double claiming under Icelandic law.

Voluntary carbon credits intersecting with NDCs create country–company double claiming. If you're retiring credits from a project in a country with an ambitious NDC, and the host government is also counting those reductions in its national inventory, both of you are claiming the same tonne. Article 6.2 provides that Parties may transfer Internationally Transferred Mitigation Outcomes (ITMOs) toward NDCs, but each participating Party shall apply corresponding adjustments to prevent double counting , and COP26 guidance clarified that corresponding adjustments may also apply to mitigation outcomes used in the voluntary carbon market when authorised by host Parties. The practical implication: you need to know whether the credits you buy come with a corresponding adjustment, and ESRS E1 AR 62 requires disclosure of the share (percentage of volume) that qualifies as a corresponding adjustment under Article 6.

Supply-chain and value-chain double counting happens when multiple actors in your Scope 3 footprint claim the same reduction. If your supplier invests in an insetting project to reduce their Scope 1 emissions, and you also count that reduction in your Scope 3 downstream category, you've both claimed the same tonne. The GHG Protocol Scope 3 Standard notes that Scope 3 emissions are inherently subject to double counting across value-chain actors; companies should establish contractual agreements specifying exclusive ownership of emission reductions. This is especially relevant if you're running supplier engagement programmes or co-investing in decarbonisation projects with customers.

The rules of the game: Article 6, GHG Protocol, CSRD/ESRS E1 and voluntary standards

Article 6 and corresponding adjustments: country–company double claiming

Article 6.4 establishes a UNFCCC-supervised crediting mechanism with a Supervisory Body, requiring host-Party authorisation and corresponding adjustments for credits authorised for use toward NDCs. In plain language: if a country wants to transfer mitigation outcomes to another country or authorise their use by non-state actors like companies, it must adjust its own national inventory downward so the reduction isn't counted twice.

For you, the key question is whether the credits you're buying come from projects that have host-country authorisation and corresponding adjustments. Credits without corresponding adjustments may still be high-quality from a carbon-impact perspective, but they carry double claiming risk at the national level. This doesn't mean you can't use them, but it does mean you should classify them differently in your strategy. Some market participants argue that company and country dual claims are acceptable since corporate claims are not counted in national accounts, but advocates like Gold Standard and ICAT deem this practice a risk to credibility without corresponding adjustments.

Practically, look for language in project documentation that confirms host-country authorisation. The market is still building this infrastructure, so supply is limited, but it's becoming a baseline expectation for credits aligned with the Paris Agreement's Article 6 framework.

GHG Protocol, SBTi and how credits sit next to, not inside, your inventory

SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard allows carbon credits only for residual emissions after deep decarbonisation, prohibits counting carbon credits toward meeting near- or long-term targets, and requires separate reporting of credits to avoid double counting. This is crucial: credits are for neutralising or contributing to climate action beyond your value chain, not for meeting your science-based reduction targets. If you fold credits into your inventory accounting as reductions, you risk implicit double counting of your own progress.

Similarly, GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance mandates dual reporting (location-based and market-based) and includes eight Scope 2 Quality Criteria for contractual instruments to help prevent double counting between your renewable energy purchases and emissions that are already counted elsewhere. Use both numbers in your disclosures to maintain transparency and give auditors the full picture.

For Scope 3, the Protocol is explicit: value-chain emissions are inherently shared across multiple companies, so reductions need contractual allocation to avoid everyone claiming the same impact. Without clear agreements, your supplier's efficiency gain could be counted by them, by you, and by their other customers.

CSRD and ESRS E1

Directive (EU) 2022/2464 (CSRD) mandates that in-scope undertakings disclose information about climate change mitigation, including scope 1, scope 2 and, where relevant, scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions. ESRS E1 goes further with specific calculation guidance. ESRS E1 Calculation Guidance AR 63 mandates that companies not include carbon credits issued from GHG emission reduction projects within its value chain and not include carbon credits from GHG removal projects within its value chain to avoid double counting. The logic: if a project sits inside your value chain, its impact is already reflected (or should be) in your Scope 1, 2, or 3 inventory. Buying credits from it and claiming them separately would count the same reduction twice.

Auditors will also expect you to disclose the percentage of credits that come with corresponding adjustments. This is not optional under ESRS E1; it's a required data point. Start tracking it now for every credit you retire, and build it into your registry and documentation process.

.svg)