In carbon credits, leakage (also called emissions leakage) is the increase in greenhouse gas emissions outside a project boundary that occurs because of the project's implementation. Think of it this way: you fund a REDD+ project that protects 10,000 hectares of rainforest, but deforestation simply moves 50 kilometres away to an area outside the project zone. That displacement is leakage, and it directly reduces the real climate benefit you can credibly claim.

Here's what leakage is not: it's not the same as EU ETS-style "carbon leakage," where production relocates to jurisdictions with weaker climate policies. Policy-level carbon leakage refers to the increase in CO₂ emissions outside countries taking domestic mitigation action divided by the reduction in emissions of these countries. That's a macroeconomic policy concern. Project-level emissions leakage in voluntary carbon markets is a technical assessment of whether your specific carbon credit project inadvertently shifts emissions elsewhere.

Why does this matter for your sustainability strategy? Leakage can negate the intended benefits of carbon projects , turning what looks like a portfolio of high-impact credits into one that overstates your real tCO₂e contribution. For DACH corporates under CSRD and ESRS E1, ignoring leakage creates two problems: it inflates your reported emission reductions, and it opens you to greenwashing accusations when auditors, NGOs, or media dig into your methodology.

Leakage sits alongside additionality and permanence as one of three non-negotiable quality pillars. Additionality asks: would the project happen without carbon finance? Permanence asks: will the carbon stay stored? Leakage asks: are we just moving emissions around? All three determine whether a tCO₂e claimed is a tCO₂e delivered. Miss any one, and your net zero roadmap and CSRD disclosures are built on sand.

How Emissions Leakage Shows Up in Common Project Types

Leakage isn't a single phenomenon. It shows up differently depending on project type, and understanding these patterns helps you quickly scan your portfolio for hotspots.

Activity-shifting leakage occurs when a project prevents an emissions-generating activity in one location, but that activity simply relocates. For REDD+ projects, if a project stops deforestation in one area, logging or agriculture may shift to neighboring forests outside the boundary. The tCO₂e you thought you avoided is partially or fully released elsewhere. Cookstove projects face similar risks: households may adopt improved stoves but continue using traditional fuels for certain cooking tasks (fuel stacking), or market dynamics shift fuel supply chains in ways that increase emissions upstream.

Market leakage happens when a project affects supply or demand in an established market, causing substitution elsewhere. For example, protecting a forest that supplies timber may reduce supply, raise prices, and drive production elsewhere. Jurisdictional REDD+ programs dealing with global commodity markets (palm oil, soy, beef) face this challenge: slowing deforestation in one region can inadvertently increase it in another if global demand remains constant.

Upstream and downstream leakage captures indirect effects in supply chains. Renewable energy projects may have upstream leakage associated with extraction and processing of fossil fuels that are displaced. In practice, many renewable methodologies assume this leakage is negligible, but the assumption should be interrogated, especially for large-scale projects.

Here's a practical leakage risk matrix you can use to classify projects in your portfolio:

- High risk: REDD+ and avoided deforestation (especially projects in regions with weak governance or high commodity pressure); cookstove projects (historically over-credited and under-monitored for leakage)

- Medium risk: Blue carbon and coastal wetland restoration (ecological leakage if degradation shifts to adjacent areas); soil carbon and regenerative agriculture (land-use changes and market effects)

- Low to negligible risk: Many grid-connected renewable energy projects (methodologies often assume negligible leakage); biochar and enhanced weathering (limited displacement mechanisms)

Academic studies, including research from Berkeley and analyses published in Nature Sustainability, have found that cookstove methodologies are over-credited by significant factors and that REDD+ projects often underestimate displacement. That's why internal haircuts and conservative procurement rules are not optional extras but core risk management.

How Standards and Market Guidance Treat Leakage (and Why Issued Volumes Aren't the Whole Story)

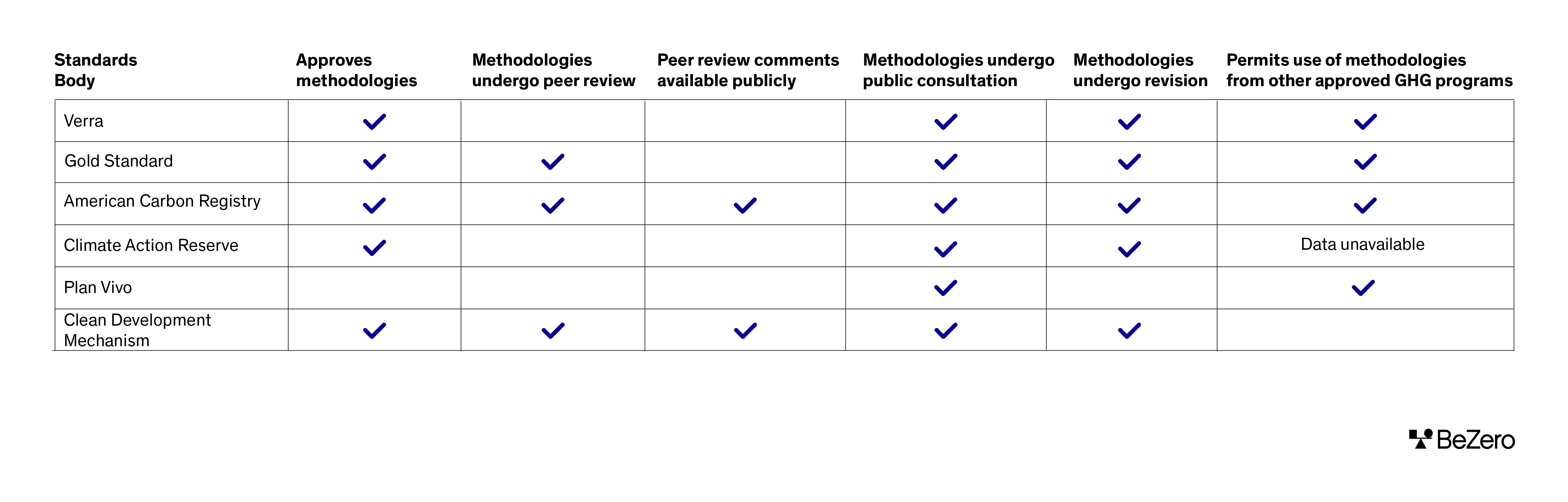

Leading carbon standards recognise leakage, but how they quantify and deduct for it varies considerably, and not all approaches are equally conservative.

Gold Standard requires projects to identify, avoid or minimize, and quantify and subtract leakage. This three-tier approach is sound in principle: first, map likely leakage pathways; second, design the project to minimize displacement; third, apply a deduction factor to the credits issued. Verra has developed detailed leakage tools for REDD+ programs, including modules for activity displacement, global commodity leakage, and ecological leakage in blue carbon projects. These tools can be methodology-specific and require projects to define a "leakage belt" (the zone where displacement is monitored) and apply empirical or default discount factors.

The challenge? Many cookstove methodologies apply a default leakage deduction of only 5%, while empirical studies suggest real leakage is much higher. Some renewable energy methodologies, especially older versions under CDM, assume negligible leakage and apply no deduction at all. That means the issued volume of credits doesn't always reflect the net climate impact once leakage is properly accounted for.

IC-VCM's Core Carbon Principles include the requirement that leakage be accounted for and minimized. This is critical for buyers: if you're procuring credits to support SBTi targets or CSRD claims, you need to ensure your projects meet CCP-level rigor. VCMI and GHG Protocol Scope 3 guidance similarly expect companies to use leakage-adjusted credits when making neutralisation or contribution claims.

Here's what this means in practice: don't take a registry's issued tCO₂e at face value. Ask:

- What leakage pathways were identified in the PDD?

- What leakage discount or deduction was applied?

- Is that factor empirical (based on observed data) or a conservative default?

- Has ex-post monitoring detected any leakage, and were additional credits cancelled?

If your project developer or broker can't answer these questions clearly, that's a red flag.

How Senken's Sustainability Integrity Index (SII) Reduces Leakage Risk for Buyers

Assessing leakage at scale across hundreds of potential projects is resource-intensive. That's where structured, data-driven due diligence becomes essential.

Senken's Sustainability Integrity Index evaluates leakage as part of a 350-datapoint "Carbon Impact" dimension, which covers additionality, permanence, and leakage together. For leakage specifically, the SII examines:

- Identification: Has the project mapped all plausible leakage pathways (activity shifting, market effects, upstream/downstream)?

- Avoidance and minimization: Are there design features (community programs, alternative livelihoods, benefit-sharing) that reduce displacement risk?

- Quantification: What leakage discount is applied? Is it empirical, conservative default, or assumed negligible? Does the methodology align with IC-VCM and leading academic critiques?

- Monitoring: Is there ex-post monitoring of leakage belts, market boundaries, or supply chains? Are monitoring reports updated with observed data?

- Ex-post adjustments: Have any credits been cancelled or discounted based on detected leakage?

Projects that rely on weak leakage assumptions (e.g., no deduction for high-risk REDD+ or 5% default for cookstoves with no empirical validation) are flagged and typically do not pass Senken's quality bar. Less than 5% of projects assessed meet the full SII standard, precisely because many fail on leakage, additionality, or permanence.

For DACH companies, this means you can leverage SII outputs directly in your audit files and ESRS disclosures. When your auditor or board asks, "How do you know leakage is accounted for?", you can point to the SII methodology note, the project scorecards, and the evidence that only projects with robust leakage treatment made it into your portfolio. That's not marketing. That's documented governance and risk management.

Leakage is not an abstract academic detail. It's a core determinant of whether your carbon credit spend delivers real, defensible climate impact. By asking the right questions, applying conservative assumptions, and treating leakage as a standard part of quality and compliance, you can manage the risk and keep your CSRD claims audit-ready.

.svg)