Key Takeaways

- Peatland restoration is a high-leverage climate solution: ~3–4% of land storing ~30% of soil carbon and ~4–5% of global emissions when drained — making it a strong candidate for beyond-value-chain mitigation in DACH climate strategies.

- Most peatland restoration credits today are high-impact avoided-emission units from rewetting drained peat; removals grow over time as sites return to net carbon sinks.

- Quality varies widely: sustainability teams should screen peatland projects for additionality, baseline robustness, permanence (hydrology and fire risk), MRV quality, and governance, ideally using a structured framework like Senken's 600+ data-point Sustainability Integrity Index.

- DACH corporates can finance peatland restoration via spot purchases, Peatland Code/MoorFutures-style domestic schemes, and multi-year offtake agreements with international projects, balancing cost, risk, and co-benefits.

- To stay CSRD- and SBTi-aligned, peatland credits should be positioned as beyond-value-chain mitigation and integrated into an Oxford-aligned portfolio that gradually shifts from avoidance-heavy nature-based solutions to more durable removals over time.

Peatlands are waterlogged ecosystems where plant material only partly decomposes and accumulates as peat over thousands of years, locking in very dense carbon stocks. Despite covering just 3–4% of the Earth's land surface, they store roughly 30% of global soil carbon. When drained for agriculture, forestry, or peat extraction, these ecosystems flip from carbon sinks to major emission sources—contributing around 4–5% of annual anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, or nearly 2 gigatonnes of CO₂ equivalent per year. For sustainability leaders at large DACH corporates, peatland restoration represents a relatively underused, high-leverage nature-based solution that can be financed through voluntary carbon markets—but only if you know how to navigate standards, integrity risks, and CSRD/SBTi constraints. This article is your practical decision guide: when to use peatland restoration in your portfolio, how to judge quality, and how to structure financing without creating greenwashing risk.

What Is Peatland Restoration

What Are Peatlands in Simple Terms

Peatlands are wetland ecosystems where waterlogged conditions slow the decomposition of dead plant material. Instead of breaking down fully, organic matter accumulates over thousands of years as a thick, carbon-rich layer called peat. Think of peatlands as nature's carbon vaults: they cover only around 3 to 4% of the Earth's land surface yet store roughly 30% of all soil carbon globally. That dense carbon stock makes them one of the most concentrated terrestrial carbon reservoirs on the planet, far outpacing forests on a per-hectare basis.

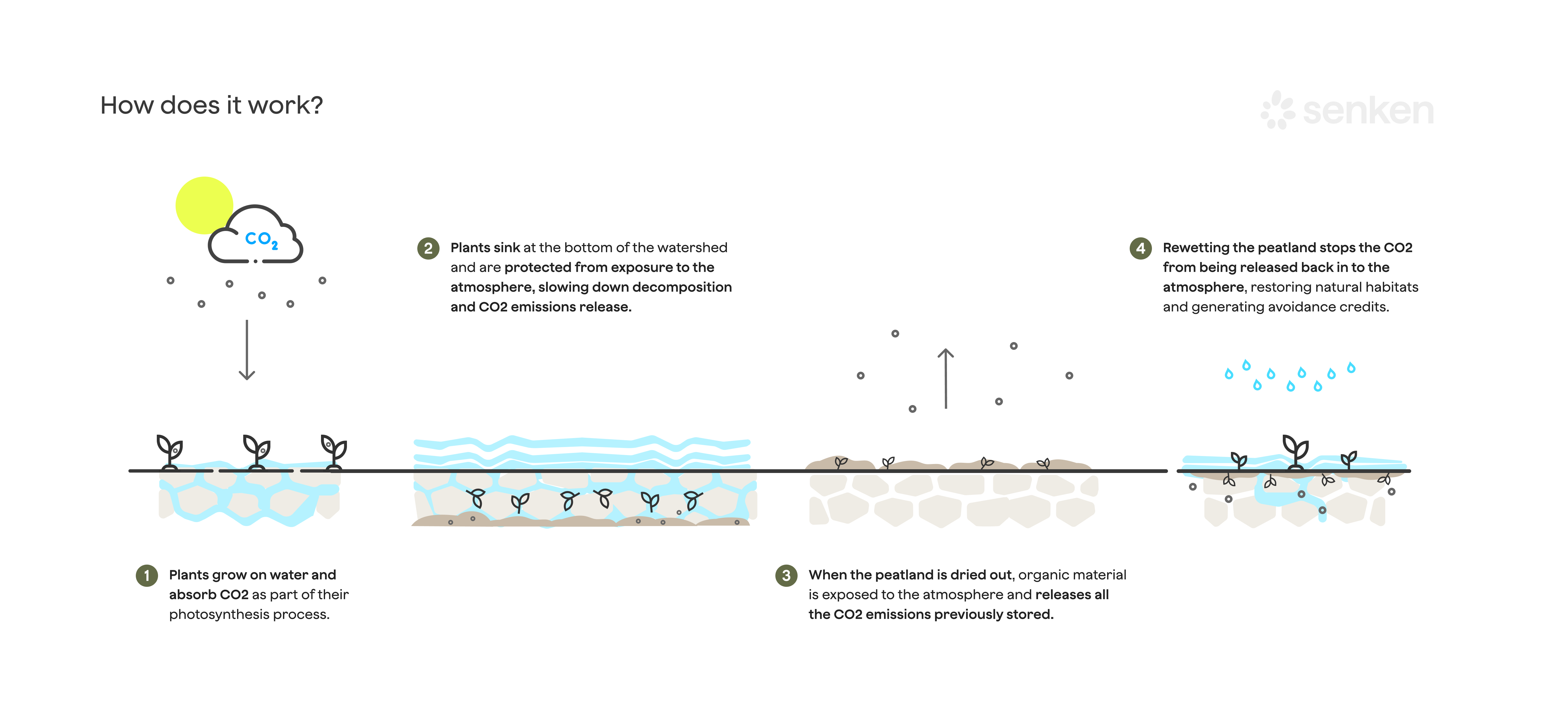

Healthy peatlands stay saturated with water, which keeps oxygen out and locks carbon in place. When they are drained for agriculture, forestry, or peat extraction, the organic material oxidizes and releases large volumes of CO₂ and sometimes nitrous oxide (N₂O) into the atmosphere. Drained and degraded peatlands are responsible for about 4 to 5% of annual anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, roughly 2 gigatons of CO₂-equivalent per year. For sustainability leaders, that disproportionate impact relative to land area is the hook: restoring even a fraction of degraded peatlands can yield significant climate benefits.

What Do We Mean by Peatland Restoration and Peat Rewetting

Peatland restoration refers to the suite of management actions that raise water tables and re-establish the ecological conditions needed for peat formation. The most common intervention is rewetting (also called hydrological restoration): blocking or infilling drainage ditches, installing peat dams or sluices, and re-profiling land surfaces to keep water levels close to the surface year-round. Once the hydrology is stabilised, natural or assisted revegetation with peat-forming plants like sphagnum moss or native sedges follows, rebuilding the living layer that drives long-term carbon accumulation.

It is worth clarifying terminology early for search engines and internal discussions. When you see "peat restoration" or "peatland rewetting," we are talking about climate mitigation projects that generate carbon credits by stopping ongoing emissions or protecting intact peatlands from future damage. This is distinct from other uses of the term "peat," such as horticultural peat bans (policy measures to stop peat extraction for gardening) or circular "re-peat" initiatives (technologies to repurpose harvested peat substrates). This article focuses squarely on restoration as a tool for corporate carbon strategies, not on peat substitutes or extraction policy.

Why Peatlands Matter for Carbon Storage

Climate Change Mitigation Potential

The climate case for peatland restoration rests on two numbers: the carbon they store and the emissions they avoid. Intact peatlands have sequestered carbon for millennia, but once drained, they flip from sinks to sources. Global assessments, including UNEP's Global Peatlands Assessment, confirm that drained peatlands emit nearly 2 gigatons of CO₂-equivalent annually, a figure comparable to the entire aviation sector. Rewetting those areas can cut emissions dramatically. Meta-analyses synthesized by Project Drawdown indicate that restoration of drained peatlands reduces emissions by an average of around 16.5 metric tons of CO₂-equivalent per hectare per year, while protecting still-intact peatlands avoids approximately 38.6 tCO₂e per hectare per year by preventing future drainage or conversion.

For corporate buyers, these numbers translate into high leverage: a relatively small land intervention can retire or avoid large volumes of emissions. That makes peatland restoration a strong candidate for beyond-value-chain mitigation in DACH climate strategies, especially when you need impact per euro spent. Over time, as rewetted sites mature, they also become net carbon sinks again, adding a removal dimension on top of avoided emissions, though that shift typically takes decades.

Water Regulation and Flood Prevention

Beyond carbon, restored peatlands act as giant sponges in the landscape. They absorb rainfall during wet periods and release it slowly, smoothing out hydrological extremes downstream. This flood-buffering function is increasingly valuable as extreme weather events become more frequent. In parts of the UK and Germany, peatland rewetting projects are explicitly marketed to regional authorities for their co-benefits in water management and reducing nutrient runoff that would otherwise degrade rivers and coastal zones.

For CSRD reporting under ESRS E2 (Pollution) and E3 (Water and marine resources), these water-quality improvements are material co-benefits you can highlight. Restoration projects often document reductions in dissolved organic carbon, nitrate leaching, and sediment loads, all of which strengthen the narrative that your carbon investment delivers broader environmental value.

Biodiversity and Ecosystem Co-Benefits

Healthy peatlands support specialized species that thrive in waterlogged, low-nutrient conditions. When you finance a peatland restoration project, you are often helping to recover habitat for rare birds, amphibians, and invertebrates, plus the plant communities (sphagnum mosses, sundews, bog orchids) that define these ecosystems. Many high-quality peatland projects carry biodiversity certifications or document contributions to national biodiversity strategies, making them attractive if your company has commitments tied to the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) or internal biodiversity KPIs.

These co-benefits also map neatly onto ESRS E4 (Biodiversity and ecosystems) disclosures. When evaluating peatland credits, ask project developers for quantified biodiversity metrics: species counts, habitat area restored, or alignment with regional conservation priorities. Projects that can show measurable gains across carbon, water, and biodiversity give you a stronger story for stakeholders and reduce the risk of being seen as narrowly focused on carbon alone.

How Peatland Restoration Works

Rewetting Degraded Peatlands

Rewetting is the cornerstone of almost every peatland restoration project. Drained peatlands typically have networks of ditches or subsurface drains that lower the water table and expose peat to oxygen, triggering decomposition. Restoration flips that by blocking ditches** with peat dams**, timber structures, or sheet piling, and by managing sluices or pumping stations to raise and stabilize water levels close to the surface throughout the year.

The timeline matters for corporate planning. Hydrological changes can happen within months to a few years after construction; you will see water tables rise and emissions drop relatively quickly. Full ecological recovery and a return to net carbon sink status, however, can take decades. That is why most peatland carbon credits today are primarily avoided-emission units rather than removals, though the accounting methodologies model the long-term trajectory toward renewed peat accumulation.

From a buyer perspective, focus on projects with robust hydrological monitoring: continuous or frequent water-level loggers, documented pre- and post-intervention measurements, and clear maintenance plans for infrastructure like dams and sluices. Those details underpin the credibility of the emission reductions being claimed.

Revegetation and Habitat Recovery

Once water levels are stable, the next step is encouraging the return of peat-forming vegetation. In temperate bogs, that often means spreading sphagnum fragments or nurse plants to help mosses colonize bare peat. In fens and tropical peat swamps, natural regeneration may be sufficient if seed sources and water chemistry are favorable, though some projects actively plant native trees and sedges to accelerate cover.

Revegetation drives the long-term carbon dynamics and the biodiversity outcomes you will want to report. Projects should document vegetation surveys at regular intervals, ideally tied to verification cycles, to show that the plant community is shifting back toward peat-building species. If a project cannot demonstrate vegetation recovery over its first five to ten years, that is a red flag; the site may be too degraded, the water management insufficient, or the baseline assumptions flawed.

Protecting Remaining Pristine Peatlands

Not all peatland carbon projects involve active rewetting. Some focus on avoided conversion: stopping planned drainage, forestry plantations, or agricultural expansion on intact peatlands. From a climate-integrity perspective, protecting an undrained peatland avoids more emissions per hectare than restoring one that is already drained, because you prevent the release of the full carbon stock rather than merely slowing ongoing decomposition.

Methodologically, these projects often sit within REDD+ frameworks (for tropical peat swamp forests) or jurisdictional conservation schemes. The additionality logic hinges on demonstrating that conversion or drainage would have happened in the baseline scenario, which requires credible evidence of threats (permits, land-use plans, regional deforestation trends). When you see large-volume peatland projects from Indonesia, for example, many are protection-focused rather than active rewetting, and the integrity debate turns on whether the baseline threat was real and whether project interventions (community patrols, alternative livelihoods, legal protections) are sufficient to maintain that protection over 30-plus years.

How Peatland Restoration Generates Carbon Credits

Carbon Sequestration and Avoided Emissions

Most peatland carbon credits on the market today are avoided-emission units: the project stops CO₂ (and sometimes N₂O) that would have been released if the peat remained drained or was newly drained. Over longer time horizons, rewetted sites transition back toward being net sinks, as new plant growth and peat accumulation outpace any residual decomposition. Methodologies typically model this trajectory, but the bulk of near-term credits come from emission reductions rather than new removals.

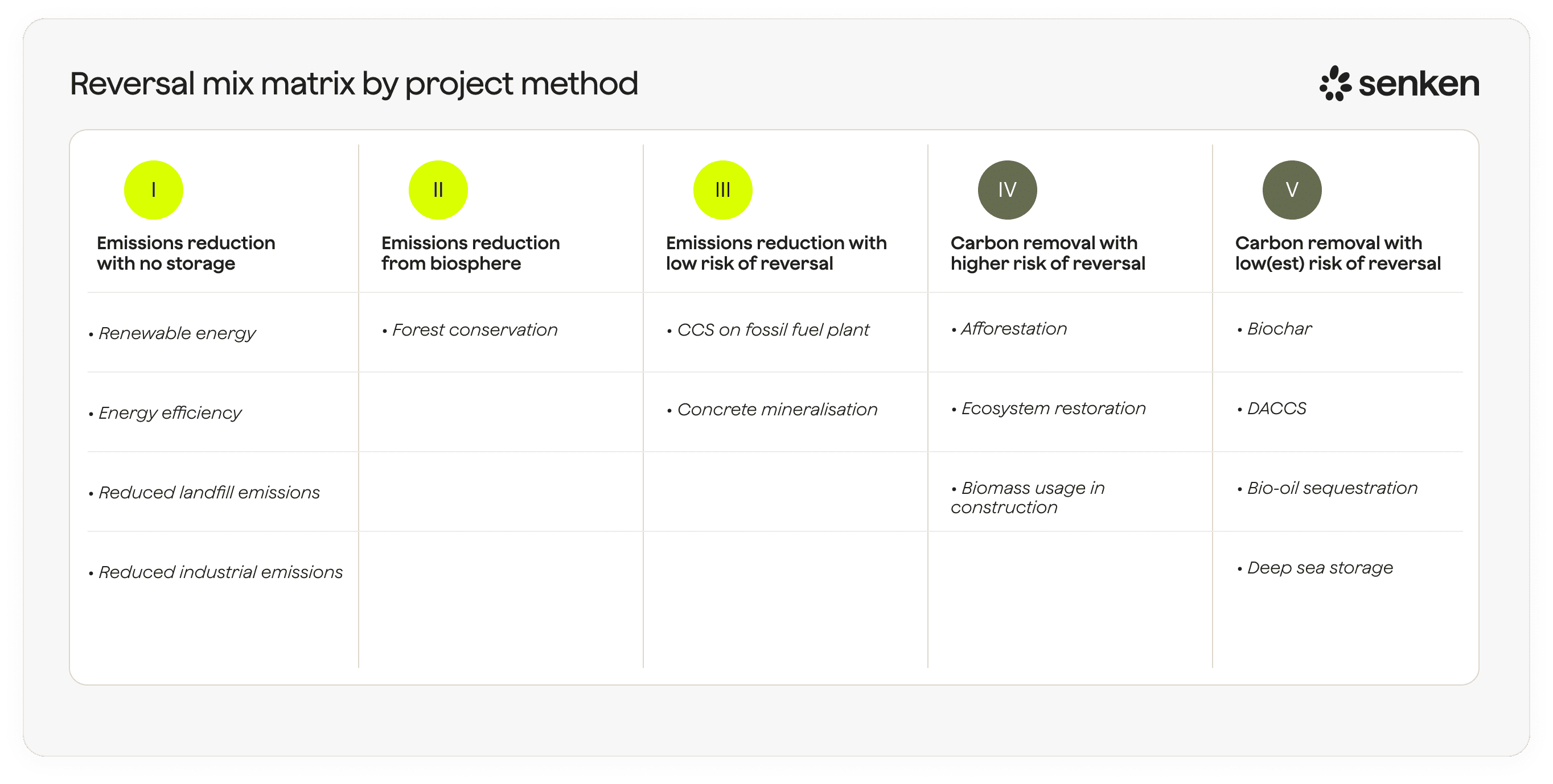

For buyers, this means peatland credits fit the "high-integrity avoidance" bucket in an Oxford-aligned portfolio. They are not durable removals in the same sense as biochar or enhanced weathering, but they are scientifically robust and address a large, otherwise unmitigated emission source. That makes them a valuable component of a balanced portfolio, especially in the 2025 to 2035 window when nature-based avoidance can dominate your mix.

Voluntary Carbon Market Standards for Peatlands

Several credible standards and methodologies support peatland restoration credits:

- Verra VCS VM0036 covers rewetting of drained temperate peatlands, using the GEST (Greenhouse Gas Emission Site Types) approach to estimate emissions based on water table depth and vegetation type. It is active and widely used in Europe and North America. An extension to boreal peatlands is currently on hold pending reassessment in 2026.

- ACRRestoration of Pocosin Wetlands methodology is active for peat soils in the US Southeast. A related ACR methodology for California deltaic and coastal wetlands is currently inactive and under revision.

- UK IUCN Peatland Code is a domestic standard generating Peatland Issuance Units (PIUs) and Woodland Carbon Units (WCUs) on the UK Land Carbon Registry. As of mid-2025, the registry lists 361 projects covering around 52,000 hectares with a lifetime claimable volume of over 9 million tCO₂e. Transactions in 2024 averaged around £25 per ton.

- MoorFutures programmes operate in several German states (Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Brandenburg, Schleswig-Holstein), with project-specific pricing historically ranging from roughly €30 to over €100 per ton, depending on co-benefits and project costs. A recent Schleswig-Holstein project listed certificates at around €123 per ton.

- Social Carbon SCM0010 is a newer peatland restoration methodology (launched October 2024) that includes a module for rewetting drained temperate agricultural peatlands, with transparent social and environmental safeguards built in.

For tropical peatlands, older Verra methodologies (VM0004, VM0027) have been inactivated, and relevant activities are being folded into updated REDD+ frameworks or a standalone tropical peatlands methodology under development. This means if you are evaluating a large Indonesian or Malaysian peat project, check which methodology it uses and whether that methodology remains active and ICVCM-aligned.

Measuring and Verifying Peat Restoration Credits

Peatland MRV hinges on a combination of direct measurements and model-based estimates. Projects typically install water-level loggers across the site to document how the water table responds to rewetting interventions. Those water-level data feed into emission-factor models (like GEST or country-specific IPCC Tier 2/3 factors) to calculate annual CO₂ and N₂O fluxes. Some advanced projects also deploy eddy-covariance flux towers or chamber-based measurements to validate model estimates with real flux data, though that level of instrumentation is still relatively rare outside research sites.

Verification follows standard registry cycles: an accredited third-party verifier reviews monitoring reports, site visits, and data quality, then approves issuance of verified carbon units (VCUs, CORCs, PIUs, or MoorFutures certificates depending on the standard). Because peatland hydrology can vary year to year with weather, robust projects include buffers or conservative assumptions to avoid over-crediting.

From a buyer perspective, strong MRV means transparent annual reports, documented calibration and maintenance of monitoring equipment, independent scientific review (not just registry verification), and willingness to adapt methods if new science emerges. If a project cannot show you continuous water-level data or explain its emission-factor choices, treat that as a quality red flag.

How to Evaluate Peatland Restoration Projects as a Buyer

Additionality and Baseline Considerations

The additionality question for peatland restoration is: would this rewetting or protection have happened anyway due to regulation, subsidy, or land-owner preference? In some jurisdictions, peatland restoration is becoming legally required or heavily subsidized, which can undermine the additionality of carbon-finance claims. Strong projects demonstrate additionality through financial analysis (showing that carbon revenue is necessary to make the project viable), barriers analysis (identifying regulatory, technical, or social obstacles that carbon finance helps overcome), or by operating in geographies where restoration is not mandated.

Baseline credibility is equally critical. For rewetting projects, the baseline is typically "continued drainage and agricultural or forestry use." Ask: is that baseline realistic given local land-use trends and policy? For protection projects, especially tropical peat REDD+, the baseline is "drainage or conversion would have occurred." Look for documentary evidence of threats: land-use permits, concession maps, regional deforestation rates, or community testimony. If the baseline feels inflated or the threats vague, you risk buying credits that do not represent real climate impact.

Leakage is another consideration. If a peatland restoration project stops agriculture on one parcel, does that simply push farming onto another peatland nearby? Good methodologies require leakage assessments and may apply a discount or implement mitigation measures (like supporting alternative livelihoods or sustainable intensification elsewhere).

Permanence, Fire and Re-Drainage Risk

Peatland restoration projects carry specific permanence risks that differ from forests. The primary threats are re-drainage (if land-use policy changes or infrastructure fails) and fire (especially in tropical peat, where drained and degraded peatlands are extremely flammable). To assess permanence, look for:

- Legal safeguards: conservation easements, long-term land-use contracts, or protected-area designations that prevent future drainage.

- Fire management plans: active monitoring (satellite hotspot detection, community patrols), firebreaks, rapid-response teams, and coordination with local fire services. In Indonesian peat projects, fire risk is a major reputational and carbon-integrity concern; credible projects publish annual fire reports and maintain on-the-ground capacity.

- Hydrological resilience: robust infrastructure (well-engineered dams, redundant water control) and realistic maintenance budgets over 30-plus years.

- Reversal buffers: many standards require projects to contribute a percentage of issued credits into a pooled buffer to cover reversals across the portfolio. Check that the project participates in a buffer mechanism and that the buffer is adequately sized for the risks.

Monitoring periods for peatland projects are typically long (30 to 100 years under codes like the UK Peatland Code), reflecting the slow nature of peat dynamics. That long tail matters for your own planning: if you buy credits from a project with a 50-year commitment, you want assurance that governance and funding will persist.

MRV Quality, Co-Benefits and Community Impact

High-quality peatland projects feature transparent and continuous MRV. Specifically, look for frequent (ideally continuous) water-level monitoring across representative site conditions, documented vegetation surveys at regular intervals, transparent selection and publication of emission factors, and independent scientific input (not just registry verification). If a project uses flux measurements (chamber or eddy covariance), that adds confidence but is not yet standard practice; most projects rely on water-level proxies and model-based factors, which is acceptable if done conservatively.

On the co-benefits side, map project claims to measurable outcomes. For biodiversity, ask for species inventories, habitat-condition indices, or documented contributions to national biodiversity strategies. For water quality, look for nutrient load measurements or downstream water-quality monitoring. For community benefits, review benefit-sharing arrangements, employment numbers, capacity-building programs, and evidence of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC) if indigenous or local communities are involved.

This is where a structured evaluation framework like Senken's Sustainability Integrity Index becomes valuable. Rather than reinventing due diligence internally, leverage a partner that systematically assesses hundreds of data points across Basic Project Details, Carbon Impact, Beyond Carbon, Reporting Process, and Compliance & Reputation. That rigor is what separates the top 5% of projects from the rest, and it is what your auditors and board will expect to see documented.

Challenges and Risks in Peatland Carbon Projects

Scientific and Methodological Uncertainty

Peat carbon fluxes are inherently variable and harder to measure than aboveground forest biomass. Emission factors depend on water-table depth, vegetation type, soil chemistry, and climate, all of which can shift year to year. Most methodologies use conservative defaults or Tier 2 approaches to manage that uncertainty, but it means there is always a range of possible outcomes.

Best practice is to use conservative baselines and factors, apply independent scientific review during project design, and align with ICVCM Core Carbon Principles or equivalent integrity frameworks to ensure that uncertainty is handled transparently. If you see a methodology that has been recently inactivated (like some older tropical peat swamp methods under Verra), treat projects using it cautiously and ask whether they plan to transition to an updated, active methodology.

Buyers should also be aware that peatland science is still evolving. New flux data, remote-sensing techniques, and understanding of microbial processes may lead to methodology updates. Credible projects and standards adapt to new science; less credible ones may resist updates that would reduce credit volumes.

Project Implementation and Long-Term Management Risks

Peatland restoration is operationally complex. Raising water levels can conflict with neighboring land uses (farmers worried about flooding, infrastructure at risk). Community acceptance is critical, which is why strong projects invest heavily in stakeholder engagement and benefit-sharing. Practical challenges include maintaining dams and sluices over decades, managing vegetation (invasive species can colonize before natives return), and securing long-term financing for monitoring and adaptive management.

Underperformance or reversal can occur if infrastructure fails, if a major fire burns through a site, or if land-use policy changes allow re-drainage. That is why governance and financial sustainability are as important as the hydrology. When you evaluate a project, ask about the long-term funding model: is carbon revenue alone sufficient, or is there public co-financing, endowment funding, or other revenue (e.g., paludiculture, ecotourism) to ensure the project can meet its commitments over 50 or 100 years?

Policy, Market and Reputation Risks

Peatland restoration sits at the intersection of carbon markets, agricultural policy, and conservation law, all of which can shift. Recent examples include Indonesia's changing rules on forest carbon project approvals (which paused issuance for major projects in 2022-2023) and Verra's inactivation of certain peat swamp methodologies. These changes create delivery risk: a project that looks solid today may face regulatory or methodological headwinds tomorrow.

Reputational risk is also real. Media scrutiny around over-crediting, fire events, or governance controversies can taint projects, even if they are scientifically sound. To manage these risks, diversify across geographies, standards, and project types within your peatland allocation, and work with intermediaries who continuously monitor policy and methodology changes. If a project or methodology faces public controversy, have a plan: can you retire and replace those credits, or do you defend the science?

Ultimately, robust due diligence and a diversified portfolio let you treat peatland restoration as a calculated, manageable part of your climate strategy rather than a reputational gamble.

How Companies Can Finance Peatland Restoration Through Voluntary Carbon Markets

Spot Purchases Versus Multi-Year Offtake Agreements

When you are ready to buy peatland credits, you have two main routes. Spot purchases are one-off transactions for credits that have already been issued and verified. They are straightforward, fast, and useful for near-term neutralization needs or pilot programs. Spot buying lets you test the market, understand pricing, and build internal experience without long-term commitment.

Multi-year offtake agreements, by contrast, commit you to purchase a specified volume of credits from a project over several years, often at a fixed or indexed price. Offtakes provide price certainty (locking in today's rates before the broader market tightens), secure future supply (critical as demand grows), and directly support project financing (developers can use contracted revenue to raise capital for infrastructure and operations). For large corporates with long net-zero roadmaps, offtakes aligned with your emissions trajectory make strategic sense: you phase in peatland credits as part of a planned portfolio shift from avoidance-heavy to more durable removals over time.

Contractual terms to negotiate in an offtake include volume commitments, delivery schedules and vintage mix (do you want credits issued annually or a single forward delivery?), make-good clauses for under-delivery (what happens if the project generates fewer credits than expected?), price structure (fixed, indexed to inflation or carbon market benchmarks, or tiered based on external ratings), and quality conditions (e.g., credits must remain ICVCM CCP-eligible, maintain external ratings above a threshold, or pass your internal SII-style evaluation).

Domestic Schemes (Peatland Code, MoorFutures) Versus International Projects

DACH corporates often face a choice between domestic or regional European peatland projects and large-scale international projects. Domestic schemes like the UK Peatland Code and Germany's MoorFutures deliver strong local co-benefits (water quality, biodiversity, rural jobs), alignment with regional policy priorities, and easier stakeholder communication ("we are restoring peatlands in our own backyard"). Prices are typically higher: Peatland Code credits averaged around £25 per ton in 2024, and MoorFutures projects have ranged from €30 to over €120 per ton depending on project specifics.

International projects, particularly tropical peat REDD+ initiatives like Indonesia's Katingan Mentaya or large US wetland restoration programs, offer greater scale and often lower per-ton prices (recent indications for Indonesian peat credits in the mid- to high single-digit US$ per ton range, US Pocosin-type projects around $15–20/t). They also bring different co-benefit profiles (protecting endangered species like the Sumatran tiger, supporting remote indigenous communities) but come with added due-diligence complexity around governance, policy stability, and methodology transitions.

A pragmatic portfolio approach is to allocate a portion of your budget to domestic schemes for their reputational and co-benefit value, while sourcing larger volumes from well-rated international projects to achieve scale and cost efficiency. That mix also diversifies your risk: if one geography faces a policy freeze or methodology change, you are not entirely exposed.

Contract and Price Structuring for DACH Corporates

Legal and procurement teams will need clear guidance on structuring peatland credit purchases. Key contractual elements include:

- Volume and delivery: specify annual or cumulative volumes, acceptable vintage ranges, and delivery timelines. Build in flexibility for modest under-delivery (e.g., 90% performance threshold) with a remedy (price reduction, replacement credits, or extension).

- Price and indexation: decide whether to lock a fixed price per ton or index to an external benchmark (e.g., a carbon market index, CPI, or agreed formula). Fixed pricing provides budget certainty; indexation can protect both parties if market conditions shift dramatically.

- Quality and compliance conditions: require that credits meet defined standards (e.g., Verra VCS + CCB, ACR, ICVCM CCP-Approved categories, minimum external rating scores from Sylvera or BeZero). Include audit rights so your team or auditors can request project documentation.

- Retirement and title transfer: clarify who retires the credits, in which registry, and when. Ensure you receive clear title and that credits are not double-claimed.

- Force majeure and termination: define what happens if the project suffers a major reversal (fire, policy shutdown) or if regulatory changes make the credits unusable for your intended purpose.

If negotiating multi-year offtakes feels complex, this is where working with a procurement partner like Senken adds value. Senken can structure agreements that balance your risk tolerance, budget, and compliance needs while leveraging their market relationships to secure favorable terms and access to high-integrity supply.

Integrating Peat Restoration Credits into Your Carbon Strategy

Positioning Peatland Credits Within SBTi and CSRD Guardrails

Under current SBTi guidance, peatland carbon credits (like all voluntary carbon credits) should be positioned as beyond-value-chain mitigation (BVCM), not as substitutes for actual scope 1, 2, or 3 reductions. Your net-zero target hinges on cutting your own emissions to the extent feasible; peatland credits finance climate action outside your value chain and help you address residual emissions or accelerate global mitigation while you implement deeper cuts. Framing them correctly is essential to avoid accusations of greenwashing or target-washing.

CSRD disclosure requirements (ESRS E1 on Climate Change) mandate transparency about the type, quantity, and use of carbon credits you purchase. You must disclose the standard or methodology, the project location and type (e.g., peatland rewetting in Germany under MoorFutures, or tropical peat protection in Indonesia under Verra VCS + CCB), the vintage, and whether credits are used for compensation claims or purely as BVCM. Strong documentation is non-negotiable: contracts, registry retirement certificates, project MRV reports, and scorecards that map to your internal quality criteria.

When your auditor or ESG rating agency asks about peatland credits, you want to show a clear rationale (high mitigation potential per hectare, alignment with your biodiversity or water commitments), evidence of rigorous evaluation (link to your due-diligence framework or Senken's SII assessment), and transparent accounting (no double-counting, no exaggerated claims). That level of rigor turns peatland credits from a compliance checkbox into a strategic asset in your sustainability narrative.

Using Oxford Principles to Plan the Shift From Avoidance to Removals

The Oxford Offsetting Principles recommend that corporate climate strategies shift over time from predominantly avoidance-based offsets to increasingly durable removals, reflecting the reality that long-term net-zero requires actively drawing carbon out of the atmosphere, not just preventing new emissions. Peatland restoration fits the Stage 1 to Stage 2 portfolio logic: today, most peatland credits are high-integrity avoidance (stopping emissions from drained peat or protecting intact peat), which is appropriate for your near-term BVCM while you drive down scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. Over the next decade, you will want to layer in more durable removals such as biochar, enhanced rock weathering, and eventually direct air capture to align with the Oxford trajectory.

Practically, this means planning a phased portfolio evolution. For 2025–2030, you might allocate 50–70% of your carbon budget to nature-based avoidance (including peatland restoration, forest protection, and some ARR), with 30–50% going to nature-based removals (ARR where it is genuinely additional, blue carbon, or soil carbon) and a small but growing share of tech-based removals. By 2030–2035, shift the mix so that removals constitute 50% or more of your annual purchases, with a rising share of high-durability (1000+ year) options. Peatland restoration remains valuable throughout, but its role evolves from a core mitigation lever today to one component of a more durability-focused mix later.

Aligning with SBTi's draft Net-Zero Standard 2.0, which introduces interim removal factors rising from 28% in 2030 to 100% by 2050, you can map your peatland allocation accordingly. Since peatland credits are primarily avoidance in the near term, they help you meet today's voluntary BVCM goals while you build access to the removal supply you will need in the 2030s.

Practical Portfolio Design for a DACH Corporate

Let's make this concrete. Imagine a large industrial or telecom company headquartered in Germany with annual scope 1+2 residual emissions of 50,000 tCO₂e after maximum feasible reductions and a commitment to neutralize those residuals annually as part of a credible net-zero pathway. A practical 2025 portfolio might look like this:

- 20% domestic/regional peat and forest (10,000 tCO₂e): UK Peatland Code projects, MoorFutures in Germany, or local ARR under the Woodland Carbon Code. Higher price per ton (€50–120) but strong stakeholder story and alignment with EU biodiversity and water frameworks.

- 40% high-quality international nature-based (20,000 tCO₂e): Tropical peat protection (e.g., Katingan Mentaya), high-rated REDD+ in Latin America or Africa, mangrove restoration in Southeast Asia. Priced around $10–25/t depending on ratings and scale, delivering cost efficiency and global impact.

- 30% nature-based removals (15,000 tCO₂e): Afforestation/reforestation projects with strong additionality, blue carbon (seagrass/mangrove), or regenerative agriculture soil carbon. Priced $25–50/t. This slice begins building your removal profile.

- 10% tech-based removals (5,000 tCO₂e): Biochar or enhanced rock weathering. Priced $100–250/t. Small share today, but you are learning, locking early supply, and positioning for the shift.

Within this mix, peatland restoration sits primarily in the first two buckets (domestic schemes and international protection), contributing perhaps 15,000–20,000 tCO₂e total. That gives you a concentrated climate impact (peatlands deliver high mitigation per hectare), diversification across geographies and risk profiles, and a narrative that balances local action with global reach.

As you move toward 2030, you gradually rebalance: hold or slightly reduce nature-based avoidance (including peat protection), grow the nature-based removals and especially the tech-based removals shares, and increase the average durability and additionality of the entire portfolio. Peatland credits remain part of the story but are joined by more long-duration removals as those markets scale and your internal targets evolve.

Building a Climate Portfolio with Peat Restoration Projects

Why Treat Peatland Restoration as a Portfolio Component, Not a One-Off Bet

Too many companies approach carbon credits as ad hoc procurement: a vendor pitches a project, the sustainability team runs a quick check, and you buy a batch of credits. That reactive approach leaves you exposed to quality risk, price volatility, and missed opportunities. A better strategy is to treat peatland restoration (and all carbon credit categories) as strategic portfolio components with defined roles, risk-return profiles, and intended outcomes.

Peatland restoration's role in your portfolio is to deliver high-leverage nature-based avoidance with strong co-benefits, moderate permanence (decades to centuries in well-managed sites), and alignment with water and biodiversity goals. It is not the whole answer; you also need forests for ecological connectivity, tech-based removals for durability, and potentially blue carbon or soil carbon for other co-benefit stories. By setting a clear allocation (e.g., 15–30% of your annual BVCM budget to peatland projects), you avoid over-concentration in any one risk, ensure you are learning across multiple project types, and make internal budget planning transparent and predictable.

This portfolio logic also simplifies stakeholder communication. Your board wants to know the strategy, not a laundry list of individual projects. You can say, "We allocate 20% to domestic peat and forest to support regional biodiversity and water goals, 40% to high-rated international nature-based projects for cost efficiency and global reach, and 40% to removal pathways to align with Oxford Principles and SBTi's evolving requirements." That is a strategy; everything else is execution.

Governance, Documentation and Audit-Readiness for DACH Companies

Strong governance means formalizing your carbon credit procurement criteria in internal policy. Document the minimum standards you will accept (e.g., Verra VCS or equivalent, ICVCM CCP-Eligible program status, no methodology on a public watchlist, minimum external rating if available), the additional screens you apply (additionality tests, permanence safeguards, co-benefit requirements, governance checks), and the approval process (who signs off, what documentation is required, how often you review and update the policy).

For peatland credits specifically, your policy might stipulate that all projects must demonstrate continuous water-level monitoring, transparent baseline documentation, and either legal protection or long-term contracts securing the land against re-drainage. Build those criteria into your RFP templates when you solicit proposals from developers or brokers, and ensure your procurement team understands the rationale so they can push back on low-quality offers.

Audit-readiness means assembling an evidence pack for each credit purchase: the signed contract or purchase agreement, the registry retirement certificate with serial numbers and vintage, a copy of the project's most recent verification report, a summary scorecard showing how the project meets your quality criteria (this is where Senken's SII scores or equivalent come in), and a clear statement of how you are using the credits (BVCM, specific neutralization claim, etc.). Store all of this in a central system (a simple SharePoint folder or a dedicated carbon accounting platform) so that when your auditor, CSRD assurance provider, or an ESG rating agency asks, you can produce everything in minutes, not weeks.

This level of discipline also protects you from future regulatory changes. If the EU tightens Green Claims rules or SBTi introduces stricter BVCM documentation requirements, you want to be able to show that you did rigorous due diligence and made conservative, evidence-based choices.

When to Work With a Procurement Partner

You should consider working with a specialized carbon procurement partner when:

- Internal capacity is limited: your sustainability team has dozens of priorities and cannot dedicate the time to track methodology changes, vet project developers, and negotiate contracts across multiple geographies.

- You need multi-year offtake agreements: structuring forward contracts with delivery risk, price indexation, and quality remedies is complex and benefits from market expertise and legal templating.

- Audit and board pressure is high: your auditors or board are asking hard questions about integrity, and you need external validation and documentation to demonstrate you are not just checking boxes but applying genuine rigor.

- You want access to curated, high-integrity supply: the market is flooded with low-quality projects. A partner like Senken that screens projects through a 600+ data-point framework and accepts fewer than 5% of candidates gives you confidence that the credits in your shortlist are genuinely high-integrity, not just registry-compliant.

- Regulatory and policy landscapes are shifting: keeping up with ICVCM updates, methodology inactivations, CSRD guidance, and SBTi consultations is a full-time job. A partner brings that intelligence as part of the service.

The value proposition is not just procurement efficiency but risk mitigation and strategic alignment. Senken, for example, designs Oxford-aligned portfolios that balance avoidance and removals, sources projects that meet both ICVCM and CSRD expectations, provides transparent scorecards and traceability, and can structure multi-year deals with price and supply certainty. That turns carbon procurement from a compliance headache into a strategic capability that supports your broader net-zero roadmap.

If you are ready to explore a structured, high-integrity peatland portfolio or want a scoping session to map your needs, that is the conversation to have next.

.svg)