Unavoidable emissions are the subset of residual emissions that remain after your company has deployed all technically and economically feasible abatement measures. Think of them as the last 5–10% of your footprint that you can genuinely justify to auditors, investors, and regulators as not yet eliminable within your transition plan horizon. But here's the catch: what counts as "unavoidable" is increasingly a governance decision, not a technical footnote. Under the SBTi Net-Zero Standard, you're expected to cut around 90% of emissions before neutralising residuals with permanent carbon removals. CSRD and ESRS E1 now require you to disclose your decarbonisation levers, explain what remains, and back it all with an audit-ready trail. In Germany, vague "climate neutral" claims are already triggering legal challenges. This guide gives you a compact, practitioner-focused playbook: a shared definition, a five-step internal decision framework, clear feasibility and documentation criteria, and a three-pillar management model (minimise, neutralise, govern) so you can turn unavoidable emissions into a well-controlled hinge between ambitious decarbonisation and credible use of removals—rather than your next greenwashing headline.

What are unavoidable emissions?

Core definition and why it must be time-bound

Unavoidable emissions are the subset of residual emissions that remain after you've implemented all technically and economically feasible abatement measures. They're not a parking lot for difficult emissions or a convenient excuse to buy offsets early. Instead, they represent the emissions you can credibly justify to auditors, regulators, and NGOs as not yet eliminable within your transition plan horizon.

The critical word here is "yet." What counts as unavoidable today will shrink as technology matures, costs fall, and your organisation builds capability. A cement plant's process emissions might be unavoidable in 2025 if carbon capture isn't commercially viable at your site, but by 2030, falling CCS costs or new clinker substitutes may shift those emissions into the "avoidable" column. That's why your internal definition must be time-bound and linked to regular reassessment cycles (typically every 2-3 years, aligned with your SBTi target reviews and CSRD reporting).

Integrated assessment models project global residual emissions of 5-10 Gt CO₂ per year by mid-century under 1.5°C pathways. For corporates, the expectation is clear: your unavoidable share should represent a small, declining fraction of your baseline footprint, not a static wedge you've ring-fenced from decarbonisation efforts.

Unavoidable vs residual vs hard-to-abate: getting the language straight

These three terms are often used interchangeably, creating confusion in board papers and supplier negotiations. Here's how they relate:

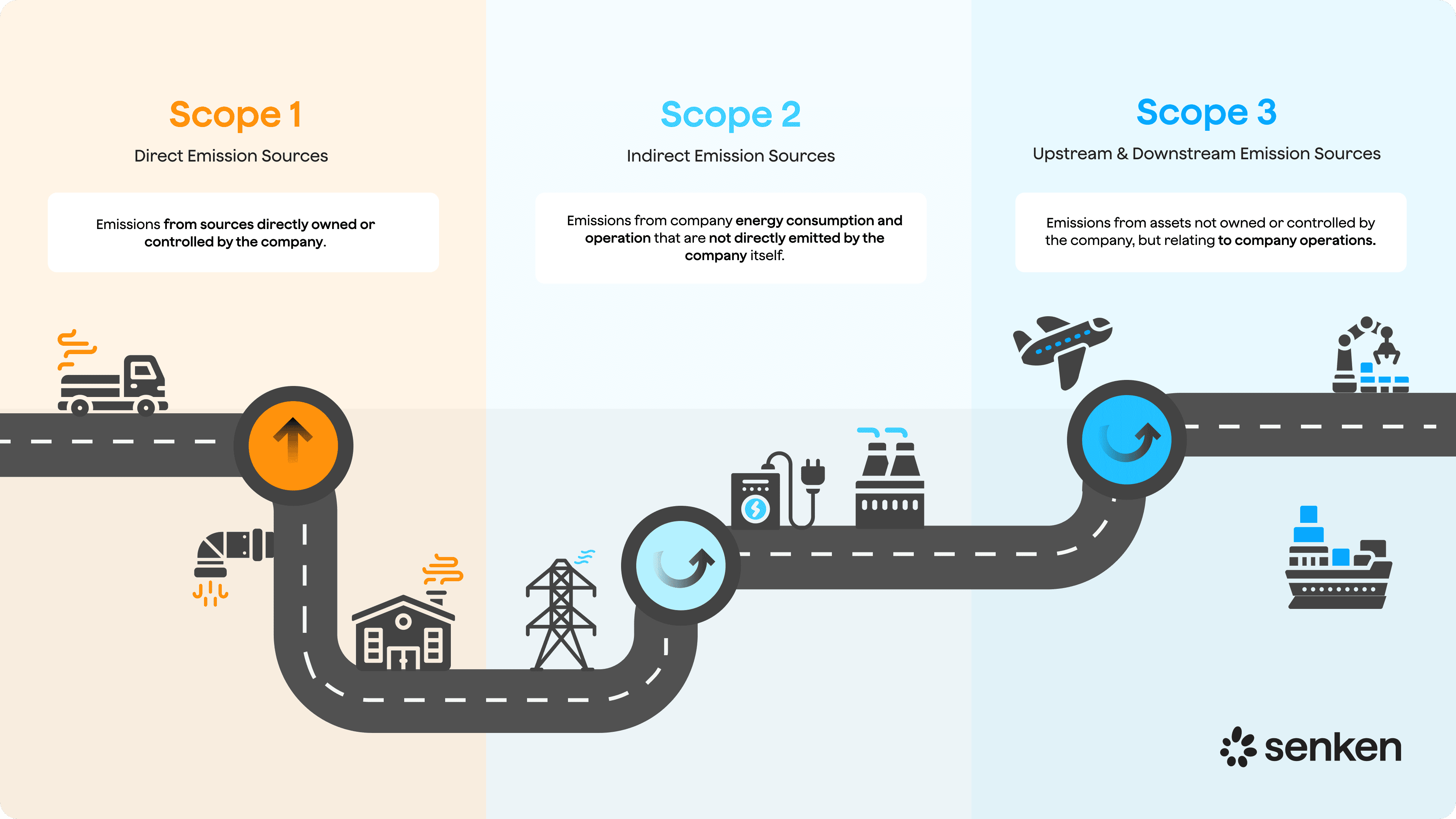

Residual emissions are all emissions remaining at the point you reach net zero. They include everything left after you've deployed your decarbonisation plan, whether or not those emissions were technically avoidable. Residual is objective: it's simply what remains.

Hard-to-abate emissions describe sectors or processes where emissions are difficult or costly to reduce using today's technology. Think high-temperature industrial heat, long-haul aviation, livestock methane, or certain chemical reactions. Hard-to-abate is a sectoral label, not a time-bound classification. Crucially, "hard to abate" doesn't automatically mean "unavoidable." Many hard-to-abate emissions can and must be reduced through innovation, efficiency, and fuel switching before you label them unavoidable.

Unavoidable emissions sit at the intersection: they're the subset of residual emissions that genuinely cannot be eliminated right now due to technological limits or prohibitive economics, despite best efforts. For example, essential business travel to locations without low-carbon transport, or Scope 3 emissions from suppliers with no renewable electricity access and no capital to switch.

Here's a simple litmus test: if you can point to a commercially mature technology or supplier alternative that you haven't implemented purely due to internal budget priorities (not genuine infeasibility), that emission is avoidable, not unavoidable.

Sector examples:

- Cement: Process CO₂ from clinker production (unavoidable until CCS or alternative binders are deployed at scale)

- Steel: Blast furnace emissions in regions without hydrogen infrastructure or affordable green electricity for electrolysis

- Agriculture: Enteric methane from livestock (partially reducible through feed additives, but full elimination not yet feasible)

- Aviation: Long-haul flights where sustainable aviation fuels aren't available or aircraft can't yet be electrified

Why unavoidable emissions matter for your net-zero and CSRD strategy

The role of unavoidable emissions in SBTi-aligned net-zero pathways

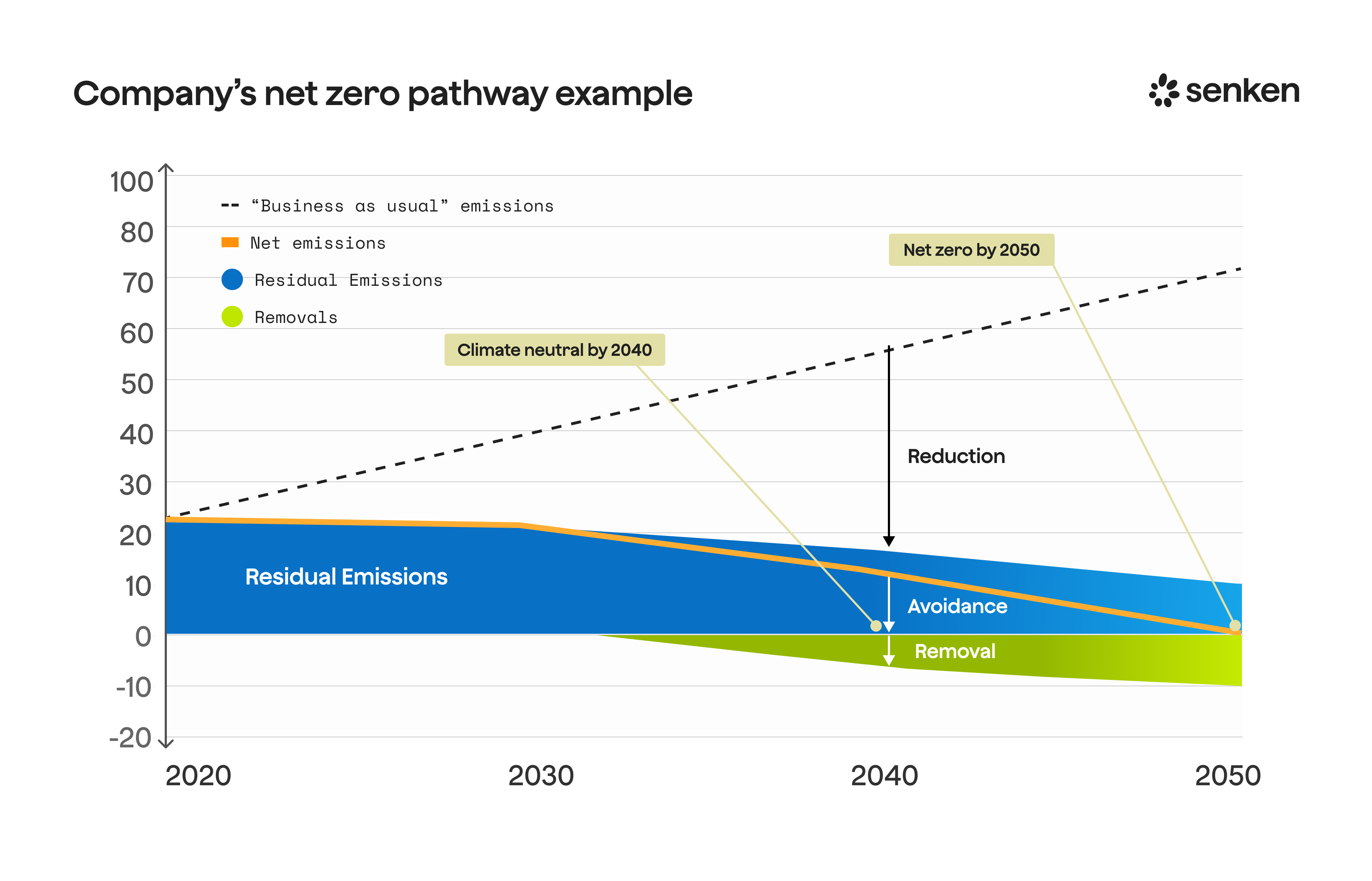

Under the SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard, achieving net zero means two things: reducing Scope 1-3 emissions by at least 90% relative to your base year, and neutralising any remaining residual emissions with permanent carbon removals at your target year. Unavoidable emissions are explicitly tied to this "residual" concept. They're what you neutralise, not what you ignore.

The draft SBTi v2 standard goes further, introducing "ongoing emissions responsibility." From 2035, Category A companies (large, high-impact firms) must start addressing at least 1% of ongoing emissions annually with carbon removals, scaling to full neutralisation by 2050. The expectation is clear: you can't wait until 2050 to buy removals for a large residual bucket. Instead, you must demonstrate continuous reduction and early, planned integration of high-quality removals for the unavoidable share.

This shifts unavoidable emissions from a technical footnote to a strategic planning input. Your finance team needs to model removal procurement costs; your operations team must justify why certain sources can't yet be abated; and your board needs assurance that the "unavoidable" label isn't masking underinvestment in decarbonisation. In practice, credible net-zero targets rest on keeping unavoidable emissions small and well-documented, then matching them with durable carbon dioxide removal (CDR) credits, not generic avoidance offsets.

What supervisors, auditors, and ESRS E1 expect to see

CSRD's ESRS E1 standard doesn't explicitly define "unavoidable emissions," but it requires you to disclose your decarbonisation levers, remaining emissions after mitigation actions, and any use of carbon credits. Auditors will assess whether your transition plan logic is coherent: if you claim large unavoidable shares while peers in the same sector achieve deeper cuts, expect challenge.

Specifically, auditors will look for:

- Clear methodology for classifying unavoidable emissions (criteria, thresholds, approval process)

- Evidence of abatement assessment (technology scans, supplier RFPs, marginal abatement cost analysis)

- Consistency with SBTi or GHG Protocol guidance (if you're signed up to SBTi, your residual definition must align)

- Transparent disclosure of which emission sources are deemed unavoidable, why, and for how long

- Defensible use of carbon credits, particularly removals, linked to clearly unavoidable emissions rather than general offsetting

In Germany, the stakes are higher. Deutsche Umwelthilfe (DUH) has successfully challenged companies making "climate neutral" claims based on low-quality offsets. The Federal Court of Justice ruled that "climate neutral" is ambiguous and companies must clarify whether it means actual reductions or mere compensation. Labelling emissions as unavoidable without robust justification, then using cheap avoidance credits, is an invitation to legal and reputational risk.

Supervisory boards increasingly ask: "How do we know our 'unavoidable' classification will hold up in three years?" The answer lies in having a documented decision framework and regular review process, not a static list.

A practical decision framework: how to decide if an emission is truly unavoidable in your company

Step-by-step classification for Scope 1, 2, and 3 sources

Here's a five-step process you can embed into your internal climate governance:

Step 1: Map the emission source and its materiality

Identify the specific activity, process, or value-chain node generating the emissions. Quantify its contribution to your Scope 1, 2, or 3 footprint and flag its financial and operational materiality (e.g., critical to product quality, safety, or regulatory compliance). Use your ESRS double materiality assessment as a starting point.

Step 2: Screen abatement options

List all potential reduction measures for that source: efficiency improvements, process redesign, fuel or technology switching, supplier engagement, or operational changes. For each option, assess technical maturity (is it commercially available and proven at scale?) and your organisation's ability to integrate it (lead time, capex, operational risk, regulatory approval).

Step 3: Evaluate economic feasibility

Calculate or estimate the marginal abatement cost (€ per tonne CO₂e) for each option. Compare this to your internal carbon price and transition plan budget. Options that fall below your cost threshold or payback criteria should be implemented before labelling emissions unavoidable. A marginal abatement cost curve (MACC) is a simple visual tool here: plot abatement potential (x-axis) against cost (y-axis) to see which measures are "no regret" or economically viable now.

Step 4: Apply "unavoidable" criteria and document

An emission qualifies as unavoidable only if:

- No technically mature, scalable solution exists today

- Or, solutions exist but exceed your cost/feasibility threshold and you've documented why implementation isn't viable within your transition plan horizon

- Or, the emission is tied to an essential function (e.g., safety-critical backup generation) with no zero-carbon alternative

Document your logic, data sources, and approvals in a standard template. Keep evidence of supplier negotiations, technology assessments, and investment cases on file.

Step 5: Set a reassessment horizon

Schedule a review in 2-3 years or when major cost/technology shifts occur (e.g., new green hydrogen supply, CCS hubs coming online). As conditions change, emissions should migrate from unavoidable back to avoidable, driving continuous improvement.

Applying technical and economic feasibility in practice

Let's ground this in relevant examples:

Scope 1 – High-temperature industrial furnace:

Your steel or glass plant runs a furnace that requires temperatures above 1000°C. Electrification is technically possible but your regional grid lacks sufficient renewable capacity and grid upgrades won't arrive until 2028. You've modelled the capex and concluded that immediate electrification would exceed €200/tCO₂e abated, well above your €100/tCO₂e threshold. Document this in your investment case, including supplier quotes and grid operator correspondence. Set a 2028 review trigger. Until then, these process emissions can be classified as unavoidable. But note: you must still pursue efficiency gains and fuel switching (e.g., partial hydrogen blending) to shrink the unavoidable share.

Scope 2 – Data centre in a low-renewable grid:

You've maximised on-site efficiency, signed the largest available renewable PPA, and installed on-site solar. Residual grid electricity emissions remain because the local grid is coal-heavy and you can't physically relocate the data centre due to latency and customer requirements. This residual Scope 2 may be unavoidable in the near term, but you must show evidence of engaging the grid operator and government on renewables expansion and consider investments in grid-connected storage or demand response.

Scope 3 – Purchased goods with no low-carbon suppliers:

You source a specialty chemical from two global suppliers; both use a carbon-intensive process and neither offers a low-carbon alternative. You've issued RFPs, engaged them on decarbonisation roadmaps, and explored substitutes, but no viable option exists within your product specifications. Document the RFP outcomes, supplier responses, and R&D efforts to develop alternatives. These upstream emissions can be classified as unavoidable, but revisit annually as supplier innovation accelerates.

Criteria, documentation, and review cadence that stand up to assurance

What 'technically feasible' and 'economically viable' should mean in your policy

To avoid subjectivity, define these terms explicitly in your internal climate policy:

Technical feasibility means:

- The technology is commercially available (TRL 8-9), not just demonstrated at pilot scale

- It's proven in your sector or analogous applications

- You can integrate it within a reasonable lead time (e.g., 3-5 years for major capex, 1-2 years for operational changes)

- Regulatory approvals are obtainable, or clear pathways exist

Economic viability means:

- The marginal abatement cost is below your defined threshold (e.g., €100/tCO₂e, or aligned with your internal carbon price)

- The payback period fits your capital planning (e.g., ≤10 years for capex-intensive measures)

- You've allocated or can reasonably allocate budget within your transition plan

- The measure doesn't compromise safety, product quality, or core business operations in ways that can't be mitigated

Crucially, "economically viable" is forward-looking: if a technology's cost is expected to cross your threshold within your next target period (e.g., 2030 near-term target), start planning now rather than claiming unavoidability.

Build these criteria into a simple decision matrix that your business units can apply consistently. Involve your finance team to agree thresholds, linking them to your organisation's cost of capital and climate ambition.

Building documentation packs for auditors, NGOs, and your supervisory board

For each cluster of emissions you classify as unavoidable (e.g., "industrial heat Scope 1," "supplier X Scope 3 purchased goods"), assemble a lean evidence pack:

1. Source description: Scope, activity, volume (tCO₂e), % of total footprint, materiality

2. Abatement assessment: List of options considered, technical maturity, integration feasibility, cost estimates (ideally a simple MACC chart)

3. Decision rationale: Why each feasible option was implemented or why unavoidable criteria apply; reference to internal carbon price and thresholds

4. Supporting evidence: Supplier quotes, RFP responses, technology vendor assessments, board investment papers

5. Review trigger: Next reassessment date and conditions (e.g., "review in 2027 or when CCS hub operational")

6. Carbon removal linkage (if applicable): Type, volume, and quality of removal credits procured to neutralise this unavoidable share

Store these packs centrally and update them during your annual CSRD cycle. When auditors or NGOs ask, "Why is this emission unavoidable?", you hand over a structured file, not a vague narrative.

Set a formal review cadence: at minimum every 2-3 years aligned with SBTi target updates, but also trigger ad-hoc reviews when major cost or technology developments occur (e.g., new government subsidy, breakthrough in your sector). Your governance committee should approve any expansion of the "unavoidable" category and receive annual updates on shrinkage achieved.

Managing unavoidable emissions: minimise, neutralise, govern

Pillar 1: Minimise – keep shrinking the 'unavoidable' bucket

Labelling an emission unavoidable today doesn't mean abandoning efforts to eliminate it tomorrow. Embed continuous improvement into your transition plan:

Action 1: Establish an "unavoidable emissions reduction roadmap."

For each major unavoidable source, map the technology or market developments that would make it avoidable (e.g., CCS at scale, green hydrogen supply, supplier capability building). Set milestones and assign ownership. Review progress quarterly.

Action 2: Invest in R&D and pilots.

Partner with technology providers, industry consortia, or research institutions to advance solutions for your hardest emissions. Even if full deployment is 5-10 years away, early engagement builds knowledge and optionality.

Action 3: Engage suppliers and value-chain partners.

For Scope 3 unavoidable emissions, don't just accept "no alternative exists." Co-invest in supplier decarbonisation, share best practices, or collaborate on joint procurement of low-carbon inputs. Make reduction of unavoidable Scope 3 a KPI in supplier contracts.

Action 4: Regularly update your MACC and reassess thresholds.

As your internal carbon price rises or capital costs fall (e.g., cheaper renewables, economies of scale), measures that were uneconomic become viable. Re-run your marginal abatement cost analysis annually.

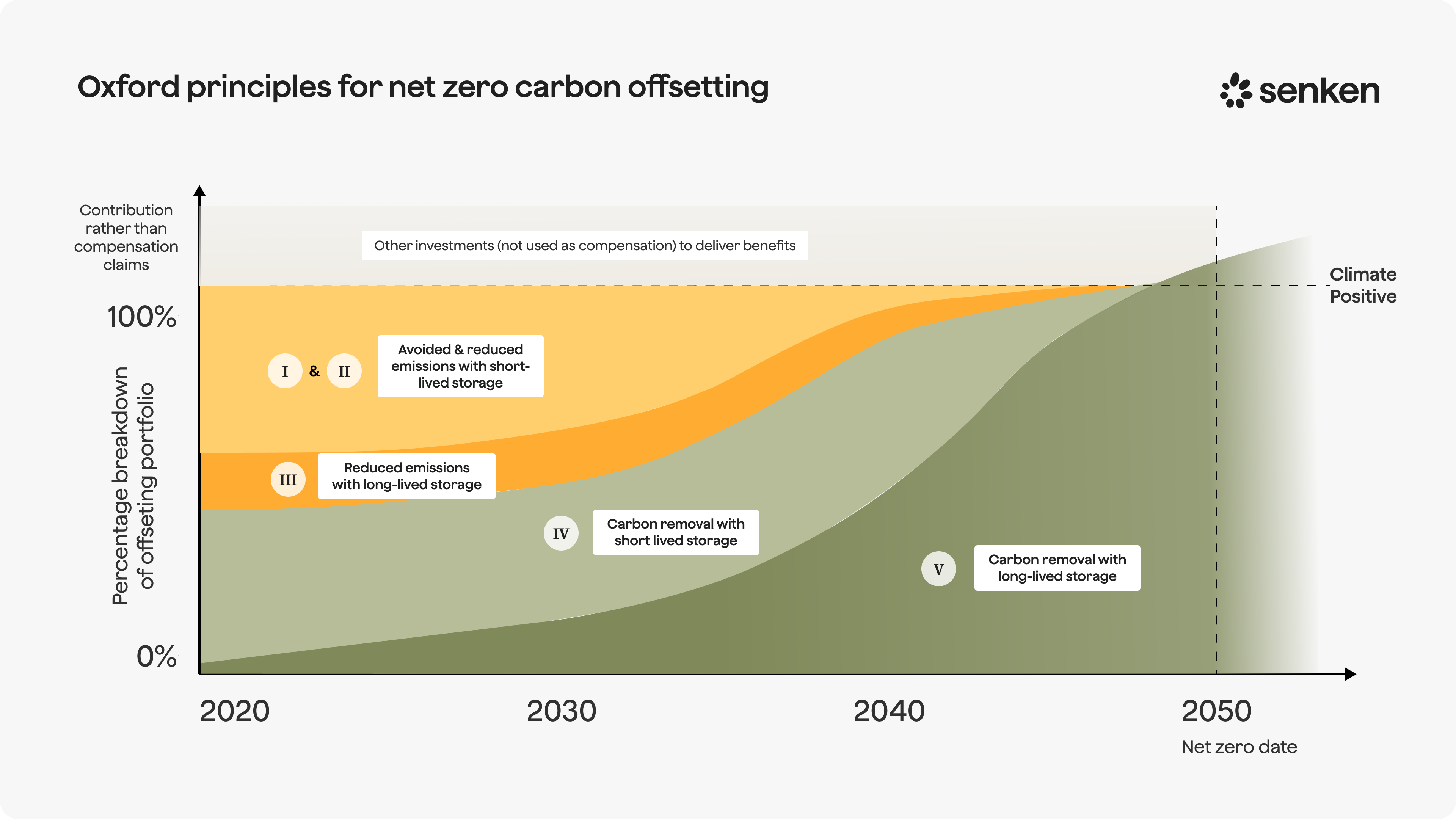

Pillar 2: Neutralise – use high-quality carbon removals in a reductions-first hierarchy

Once you've genuinely exhausted feasible abatement, unavoidable emissions must be neutralised with carbon removals, not avoided. Under SBTi and the Oxford Principles, only carbon dioxide removal (CDR) counts for residual neutralisation. Avoidance-based credits (renewable energy, cookstoves, avoided deforestation) do not offset ongoing emissions in a net-zero claim.

When to use removal credits:

- At your net-zero target year, to neutralise the small residual share remaining after 90%+ reductions

- Earlier, under SBTi v2's "ongoing emissions responsibility," starting from 2035 for Category A companies (at least 1% of ongoing emissions annually, scaling to full neutralisation by 2050)

- Voluntarily, as Beyond Value Chain Mitigation (BVCM) to support climate action beyond your value chain, but separately disclosed and not counted against your reduction targets

Quality criteria for removals used against unavoidable emissions:

- Permanence: Match durability to your climate claim. For long-term neutralisation, prefer removals with >1000 years storage (biochar, enhanced weathering, DACCS) over short-lived forestry

- Additionality: The removal wouldn't have happened without your finance

- Robust MRV: Measurement, reporting, and verification by credible third parties

- Conservative baselines and leakage assumptions: Avoid over-crediting

- Social and environmental safeguards: No harm to local communities or ecosystems

The market is shifting rapidly. By 2030, removal demand is expected to exceed supply by over 1 gigaton, and prices for high-quality durable removals could rise from ~€50/tonne today to €146/tonne. Companies that secure removal portfolios early lock in costs and access to top-tier projects. Waiting until compliance deadlines will mean higher prices and limited choice.

Pillar 3: Govern – embed decisions into climate governance and risk management

Unavoidable emissions and associated removal purchases must be governed like any other strategic risk and investment:

Action 1: Define clear approval workflows.

Who can classify an emission as unavoidable? Typically, business unit leaders propose, sustainability reviews against criteria, and a governance committee (e.g., exec sustainability council or board ESG committee) approves. Set thresholds: e.g., sources >10ktCO₂e or >1% of footprint require board visibility.

Action 2: Integrate into financial and capital planning.

Link unavoidable emissions budgets to capex allocation. If an emission is unavoidable because you can't afford the abatement capex, that's a finance decision, not a sustainability footnote. Ensure your CFO and transition plan budgets reflect this trade-off.

Action 3: Embed in internal audit and CSRD assurance scope.

Your internal audit team should periodically review unavoidable classifications and supporting evidence. When external auditors arrive for CSRD assurance, point them to your documented framework and evidence packs. Treat this like financial controls: clear criteria, documented decisions, regular review.

Action 4: Report transparently and separately.

In your sustainability report and CSRD disclosures, distinguish gross emissions, avoidable vs unavoidable shares, reductions achieved, and removals purchased. Never present removals as reductions or obscure the size of your unavoidable bucket. Transparency builds trust with investors, NGOs, and regulators.

Using carbon removal credits credibly for unavoidable emissions

Quality criteria for carbon removals linked to unavoidable emissions

Not all carbon credits are created equal. Analysis of DAX40 companies found that 68% ended up with portfolios including projects with no real climate impact. In Germany, DUH lawsuits and the Federal Court's "climate neutral" ruling have made it clear: vague offsetting claims invite legal challenge.

When procuring removals to neutralise unavoidable emissions, apply these filters:

1. Removals only, not avoidance.

Renewable energy credits, cookstove projects, and many REDD+ forestry projects are avoidance-based. The ICVCM rejected most renewable energy methodologies in 2024, and Berkeley research found cookstove credits overestimated impact by a factor of 10. For residual neutralisation, stick to carbon dioxide removal: biochar, enhanced weathering, DACCS, BECCS, or high-quality afforestation with long-term guarantees.

2. Long-term permanence.

If you're claiming net zero or neutralising emissions for decades, match that timeframe. Nature-based removals (afforestation) offer <100 years storage and carry reversal risk (fire, disease, land-use change). Technology-based removals (biochar >1000 years, mineralisation >10,000 years, geological storage >10,000 years) provide durable climate benefit. SBTi v2 expects an increasing share of novel, durable removals over time (7% by 2030, 32% by 2050).

3. Strong additionality and conservative baselines.

The removal must be additional (wouldn't happen without carbon finance) and the baseline must be realistic (not inflated to generate more credits). Watch for projects in locations where the activity is already common or subsidised.

4. Robust, third-party MRV.

Look for projects with independent verification (e.g., TÜV, SCS Global, DNV), registry approval (Verra, Gold Standard, Puro.earth), and ideally external ratings (BeZero, Sylvera, Renoster). Single-layer verification isn't enough in today's scrutiny environment.

5. Social and environmental co-benefits.

Ensure projects respect land rights, support local livelihoods, and enhance (not harm) biodiversity and water quality. CSRD's ESRS E-series expects disclosure of environmental and social impacts, so choose projects that strengthen your ESG narrative, not undermine it.

How Senken's Integrity Index and due diligence support audit-ready portfolios

Senken's Quality Framework evaluates over 600 data points per project across five dimensions: project description, carbon impact, beyond-carbon social and environmental performance, MRV robustness, and external ratings. Only projects in the top tier meet the stringent criteria needed for credible unavoidable emissions neutralisation.

This multi-layer approach reduces greenwashing risk and simplifies your audit defence. When you present a removal portfolio to your board or auditors, you can show:

- Independent quality scoring based on scientific criteria

- Cross-checked external ratings (BeZero, Sylvera)

- Verification by accredited registries

- Clear matching of credit type (permanent CDR) to claim (residual neutralisation)

- Transparent project documentation

In practice, this means you're not relying on a single registry label or vendor assurance. Instead, you're stacking multiple lines of scrutiny, which is exactly what CSRD assurance and NGO challenges demand. For companies navigating DUH-style activism and the new Green Claims Directive, Senken's due diligence becomes a key part of your compliance infrastructure, not a nice-to-have.

By integrating high-integrity removals into your unavoidable emissions strategy early, you lock in supply at current prices, build a defensible narrative, and turn carbon removal procurement from a last-minute scramble into a planned, governed process. That's the difference between managing unavoidable emissions credibly and becoming the next greenwashing headline.

.svg)