Before you can set credible policies or procurement rules, you need a shared internal vocabulary. Carbon sequestration is the process of capturing and storing CO₂ in geological, terrestrial, ocean, or product reservoirs. It sits at the heart of both nature-based and engineered climate solutions.

Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) refers to anthropogenic activities that remove CO₂ from the atmosphere and store it durably in these reservoirs. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) captures CO₂ from large-scale fossil-based energy and industry sources and permanently isolates it in geological formations . When CO₂ is captured directly from the air (DACCS) or from biomass combustion (BECCS), the storage phase is effectively carbon sequestration, making these hybrids of removal and geological storage.

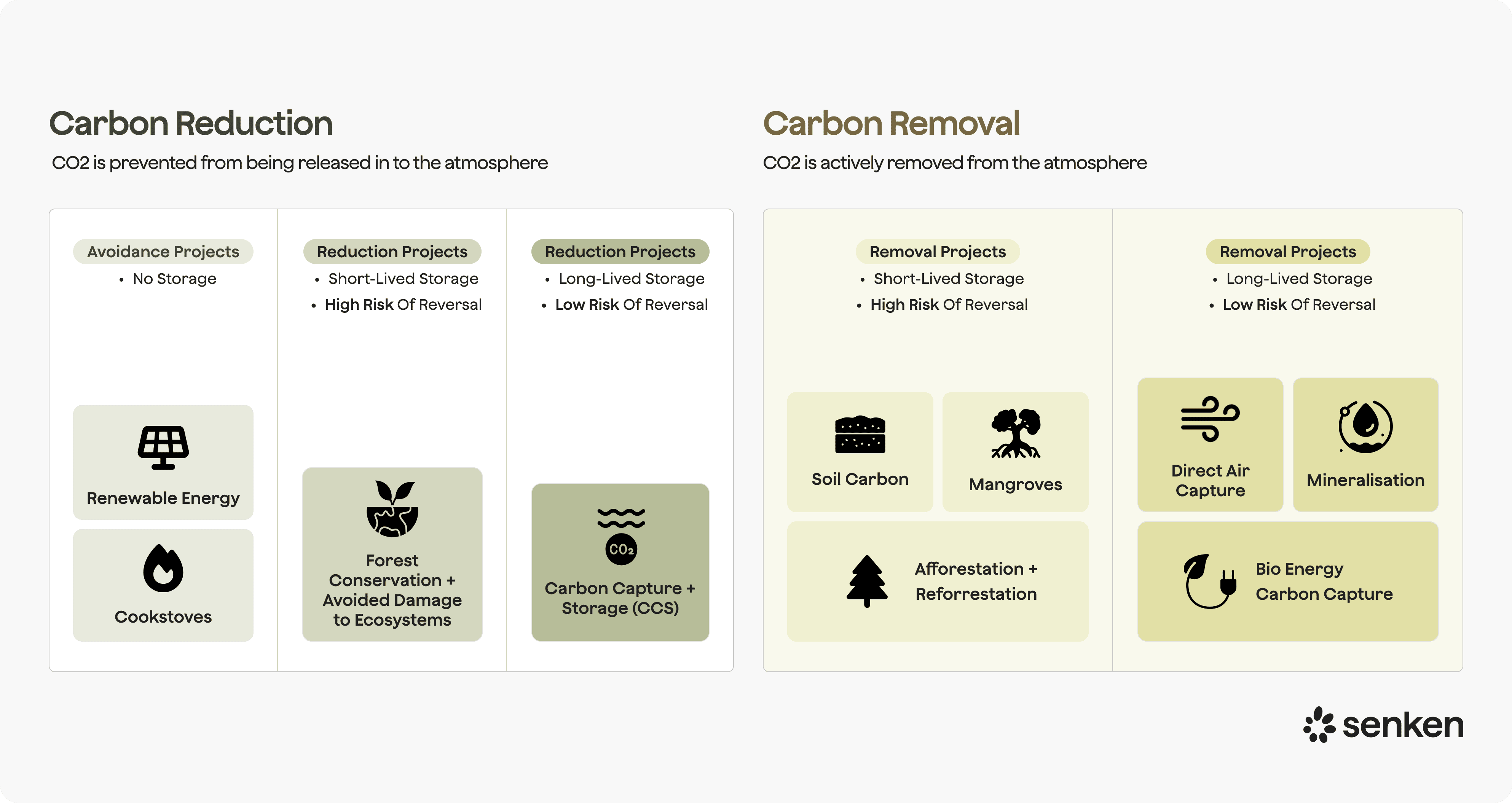

The distinction matters for corporate use. CDR credits (forests, soils, biochar, DACCS) typically support neutralisation claims under SBTi and can be used for beyond value chain mitigation. Classic avoidance or reduction credits (renewable energy, cookstoves) do not sequester carbon and are increasingly excluded from high-integrity frameworks like ICVCM. Meanwhile, CCS from point sources can reduce a facility's own emissions but does not remove legacy atmospheric CO₂, so it plays a different role in your roadmap.

For CSRD and green claims compliance, clarity on what "counts" is critical. The EU Carbon Removals and Carbon Farming Regulation (CRCF) defines four certificate types: permanent removals, carbon storage in products, carbon farming removals, and soil emission reductions . Mapping your portfolio to these categories now will save time when auditors arrive in 2026.

Comparing carbon sequestration methods: permanence, MRV and cost at a glance

Not all carbon sequestration methods are created equal. To design a defensible portfolio, you need to understand how they compare on the dimensions that matter most: permanence (how long carbon stays locked away), MRV maturity (how reliably you can measure and verify impact), cost, and market availability today.

Below is a snapshot drawn from IPCC AR6 and EU CRCF data, translated into order-of-magnitude figures you can use in steering committee slides:

Use this table to frame portfolio roles. Nature-based methods (forests, soils) offer large near-term mitigation potentials (up to ~10 GtCO₂/yr each) with relatively low average costs , making them pragmatic for 2025–2030 contributions and strong co-benefits. Engineered and geological methods (biochar, BECCS, DACCS) are currently expensive and supply constrained but will be required for long-term neutralisation of true residuals under SBTi and EU expectations post-2035.

The key insight: a phased approach lets you secure near-term volume and co-benefits with vetted nature-based carbon sequestration methods while building early exposure to durable, engineered removals that will dominate compliance-driven portfolios by 2040.

Nature-based carbon sequestration methods: forests, soils and blue carbon in practice

Nature-based sequestration remains the backbone of today's voluntary carbon market, but quality varies wildly. Here's how to lean on these methods without exposing yourself to greenwashing risk.

Forests and ARR/IFM projects

Afforestation, reforestation (ARR), and improved forest management (IFM) store carbon in biomass, typically for decades to centuries . Under Verra VCS and Gold Standard, these are among the most mature methodologies with established MRV protocols.

Quality risks you must document: Reversal risk from wildfire, disease, pests, and land-use change is material. Robust projects maintain buffer pools (typically 10–30% of credits withheld in a registry pooled buffer) and have long-term management agreements with local communities or governments. Additionality can be contested if forests were unlikely to be cleared anyway; look for projects that demonstrate financial, legal, or barrier additionality through validated baseline scenarios.

When to use: 2025–2030 for volume, co-benefits (biodiversity, watershed protection, local employment), and ESG storytelling. Pair with diversified sourcing across geographies to reduce correlated reversal risk. Under CSRD, disclose the buffer mechanism and expected permanence period explicitly.

Soil carbon and regenerative agriculture

Soil carbon sequestration via croplands and grasslands has decades-to-centuries permanence and costs ranging from –45 to 100 USD/tCO₂ , with some practices (cover cropping, reduced tillage) delivering co-benefits at negative net cost to farmers. However, MRV costs can reach €4–200 /tCO₂ removed , and uncertainty is higher than forest projects due to soil heterogeneity and management sensitivity.

Quality risks: Additionality is tricky because many soil practices are being adopted for agronomic reasons regardless of carbon finance. Permanence depends on continued management; reversals can occur within a single season if practices change. Nitrous oxide emissions can offset some of the CO₂ benefit if not monitored.

When to use: If you have value-chain links to agriculture (food, beverage, retail), soil carbon projects offer strong insetting potential and alignment with regenerative sourcing commitments. Demand project-level MRV via soil sampling or remote sensing, third-party verification by TÜV or equivalent, and contractual commitments from farmers spanning multiple years.

Blue carbon and peatland/coastal wetland restoration

Peatlands, mangroves, seagrass, and kelp store carbon in sediment and biomass with permanence ranging from decades to millennia . Global mitigation potential is <1 GtCO₂/yr , so these are niche rather than scalable solutions, but they deliver exceptional co-benefits: coastal protection, fisheries support, biodiversity hotspots.

Quality risks: Governance complexity is high, especially in jurisdictions with weak land tenure or coastal management. Reversal risks include ecosystem loss, dredging, and sea-level changes . MRV can be costly and uncertain due to baseline variability in sediment carbon density.

When to use: Strategically, for companies with coastal operations or supply chains, or when stakeholder engagement and SDG alignment (Life Below Water, Climate Action) are priorities. Budget for higher due diligence and smaller volumes. Certification under Verra VM0033 or Gold Standard Coastal Ecosystem Restoration provides a baseline quality screen.

Engineered and geological carbon removal methods: from biochar to DACCS

Engineered carbon sequestration methods offer higher permanence and MRV confidence but come with higher costs and limited near-term supply. For sustainability leaders, these are your 2030–2050 compliance tools.

Biochar as a bridge between nature-based and tech

Biochar—produced by pyrolyzing biomass—stores carbon in stable solid form for centuries to millennia, with costs of 10–345 USD/tCO₂ . Co-benefits include increased crop yields, soil health, and drought resilience , making it attractive to companies with agricultural value chains.

Buyer considerations: Feedstock sustainability is critical —verify that biomass is sourced from agricultural residues or sustainably managed forestry, not primary forests. Look for Puro.earth "Biochar Carbon Removal" certification, which includes third-party lab testing of biochar stability (H:Corg ratio) and lifecycle emissions accounting.

When to use: Today, as a moderate-cost, moderate-permanence bridge. Biochar fits both near-term volume needs (it's available now at scale) and longer-term durability requirements (centuries of storage satisfy most neutralisation frameworks). It's also easier to explain to boards and customers than DACCS.

BECCS and sector-coupled removals

Bioenergy with Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) captures CO₂ from biomass combustion and stores it geologically, with permanence in the millennia range and costs of 15–400 USD/tCO₂ . BECCS is sector-coupled: it works best in industries already using biomass (pulp and paper, biofuels, district heating).

Buyer considerations: Reversal risks center on biomass sourcing unsustainability and land competition . Demand evidence that biomass is residue-based or from certified sustainable forestry (FSC, PEFC). Geological storage must meet EU CCS Directive standards or equivalent, with long-term liability frameworks in place. Verra VM0015 "Biomass combustion with CCS" offers a procurement starting point.

When to use: If you're in a hard-to-abate sector (chemicals, heavy industry, aviation) and need to show a pathway to deep decarbonisation by 2040, start small-volume offtake agreements now to secure future supply and demonstrate regulatory foresight. BECCS will feature prominently in EU and German decarbonisation scenarios; early movers lock in better pricing.

DACCS and mineralisation as high-durability options

Direct Air Carbon Capture and Storage (DACCS) removes CO₂ directly from ambient air and stores it geologically, offering millennia-scale permanence and high MRV confidence, but at costs of 100–300 USD/tCO₂ . Enhanced weathering and mineralisation offer ten-thousand-year permanence at 50–200 USD/tCO₂ , but remain at low technology readiness (TRL 3–4).

Buyer considerations: DACCS is energy-intensive ; ensure the electricity source is renewable to avoid lifecycle emissions. Look for Puro.earth "Carbon Capture from Air" or equivalent certification with transparent energy accounting. Mineralisation projects are still largely pilot-stage; if you invest, treat it as R&D with reputational upside but accept delivery risk.

When to use: For long-term neutralisation (2040–2050) under SBTi or for companies targeting "climate positive" claims. DACCS commands premium prices today but offers unassailable permanence and additionality. Consider multi-year offtake agreements (5–10 years) to lock in today's prices and secure allocation as demand surges. By 2030, SBTi is expected to require increasing shares of novel, 1000+ year durability removals; positioning now avoids a scrambled, high-cost procurement later.

Mapping carbon sequestration methods to your net-zero, SBTi and CSRD strategy

A clear method-selection framework turns abstract climate science into executable procurement policy. Here's how to operationalise it.

Step 1: Define residual emissions and time horizons

Start by revisiting your SBTi-aligned decarbonisation pathway. Identify residual emissions—the hard-to-abate emissions remaining after all technically and economically feasible reductions. For most corporates, residuals sit in Scope 3 (business travel, downstream logistics, purchased goods) and certain Scope 1 categories (process emissions in manufacturing, refrigerants).

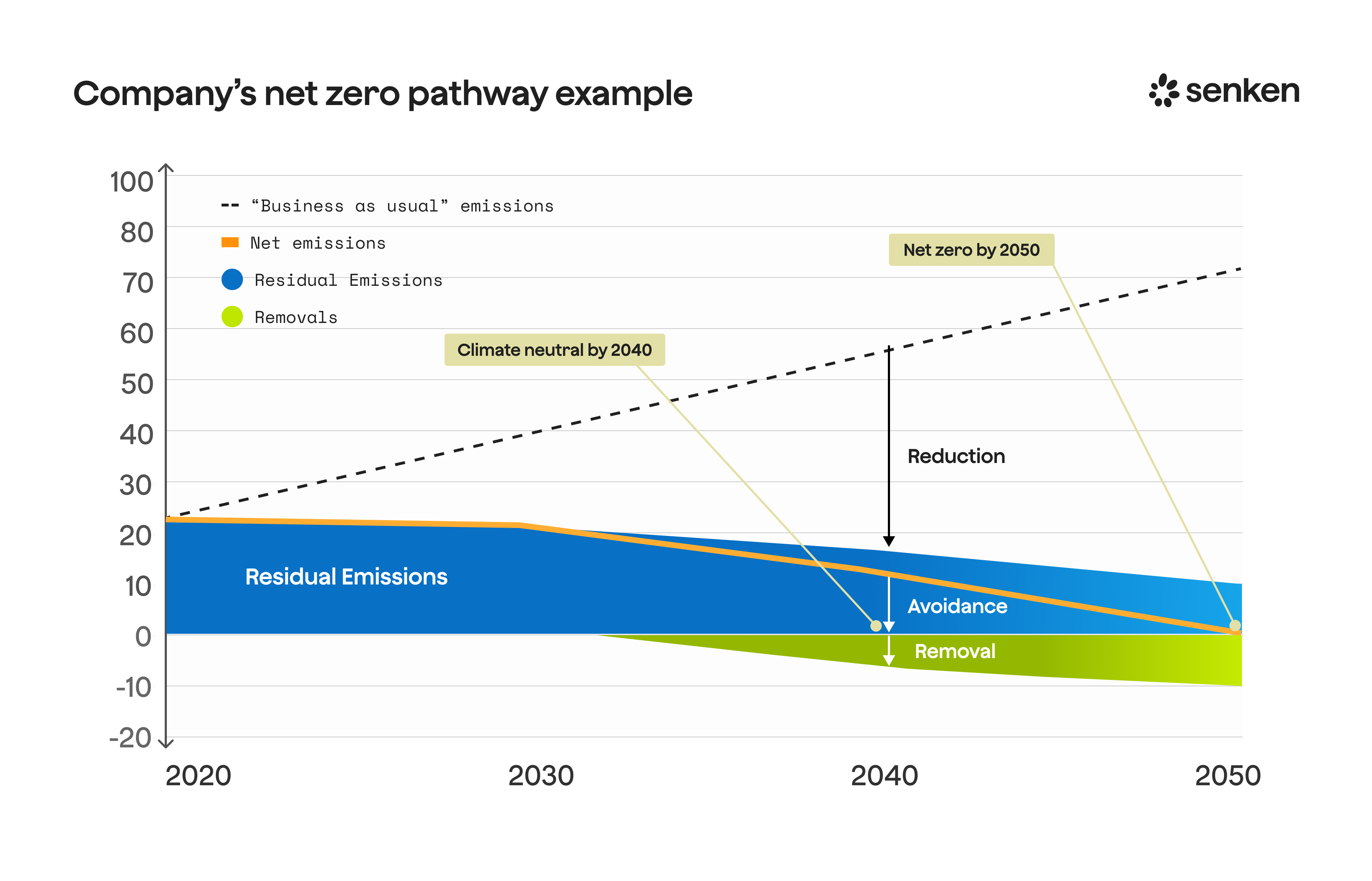

Map these residuals against milestones: What volume do you need to neutralise in 2030? In 2040? In 2050? SBTi's draft Net-Zero Standard 2.0 signals that interim removal factors will rise from 28% in 2030 to 100% by 2050, with an increasing share of novel (1000+ year) removals required —from 7% in 2035 to 32% by 2050.

This phasing tells you: you have permission to rely more heavily on nature-based methods (100+ year permanence) in the near term, but you must plan for a shift toward engineered removals over time.

Step 2: Choose methods based on permanence, risk and budget

Use the comparison table from Section 2 as your starting filter. For each time horizon, shortlist methods that meet minimum permanence thresholds, offer acceptable MRV maturity, and fit your budget envelope.

Example 2025–2030 allocation: 70% high-quality nature-based (ARR/IFM with robust buffers, soil carbon with multi-year MRV), 20% biochar, 10% DACCS or BECCS offtake as a hedge and learning investment.

Example 2035–2040 allocation: 50% nature-based, 30% biochar and enhanced weathering, 20% DACCS/BECCS.

Example 2045–2050 allocation: 30% nature-based (maintaining co-benefits and biodiversity commitments), 70% durable engineered removals to satisfy SBTi's long-term neutralisation requirements.

Layer in decision criteria: jurisdictional risk (avoid projects in countries with weak land rights or governance), co-benefits alignment (SDGs, biodiversity, community welfare), and reputational risk (avoid methodologies flagged by NGOs or rejected by ICVCM).

Step 3: Turn method choices into procurement rules and claims

Translate your shortlist into an internal carbon credit eligibility matrix. Define which methods and standards are approved for which types of claims:

- Neutralisation claims (e.g., "net-zero Scope 1+2"): require removal credits (ARR, soil, biochar, BECCS, DACCS) with minimum 100-year permanence, third-party verification, and ICVCM Core Carbon Principles alignment where available.

- Contribution claims (e.g., "supporting 1.5°C pathways" or "beyond value chain mitigation"): allow a broader set including high-quality avoidance, but maintain a floor on additionality and co-benefits.

- CSRD disclosures: document method choice, permanence assumptions, buffer mechanisms, and MRV approach in your sustainability report, ready for limited assurance under ESRS.

Link procurement rules to your Green Claims readiness. Under the EU Green Claims Directive (expected final adoption 2025–2026), environmental claims must be verified by independent third parties and substantiated with lifecycle evidence. By aligning method selection with CRCF certificate categories now—permanent removals, carbon farming, etc.—you ensure your documentation will satisfy both CSRD auditors and Green Claims enforcement.

.svg)