CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent) is the metric that converts all greenhouse gases, carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases, into a single, comparable unit so you can measure, report, and manage your climate impact consistently. CO2 is just one gas; CO2e is the common currency that lets you add methane from your supply chain, HFC leaks from your cooling systems, and CO2 from your fleet into one auditable number.

CO2, GHGs, and CO2e

What is CO2 (carbon dioxide)?

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is a naturally occurring gas and the most significant anthropogenic greenhouse gas affecting Earth's radiative balance. It's released whenever you burn fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas), produce cement, or clear forests. For corporate sustainability teams, CO2 typically accounts for the largest share of your inventory, coming from energy use, transport, and industrial processes.

What are greenhouse gases (GHGs)?

Greenhouse gases are atmospheric constituents that trap heat by absorbing and re-emitting infrared radiation. The primary GHGs relevant to corporate reporting are the seven gases covered under the Kyoto Protocol: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), sulphur hexafluoride (SF6), and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3). Each has different warming effects and lifetimes in the atmosphere.

In your operations, you encounter these gases daily: CO2 from energy and transport, methane from agriculture and waste, nitrous oxide from fertilizers and industrial processes, and fluorinated gases from refrigeration and manufacturing.

What is CO2e (carbon dioxide equivalent)?

CO2e is the common currency for greenhouse gas accounting. It converts emissions of different gases into the equivalent amount of CO2 that would create the same warming effect over a specified time horizon (typically 100 years). This allows you to add up all your GHG emissions into one comparable number for reporting, targets, and carbon credits.

For example, if your facility leaks 1 kg of methane, that equals roughly 30 kg CO2e (using IPCC AR6 values for fossil methane). Your total footprint in CO2e includes all seven gases, weighted by their relative impact.

CO2 vs CO2e: how they connect in your reporting

Think of it this way: CO2 is one specific gas. GHGs are the family of climate-warming gases. CO2e is the metric that aggregates them all. When you report your company's emissions under CSRD, GHG Protocol, or SBTi, you report in tonnes CO2e (tCO2e), not just tonnes of CO2. This ensures you're accounting for all climate impacts, not just the biggest gas.

Standard units: Use tCO2e (metric tonnes) for group-level reporting. Some contexts use kg CO2e for product-level footprints or MTCO2e (million tonnes) for national inventories, but tCO2e is the corporate default. Consistency matters: pick one unit and stick with it across your business to avoid reconciliation headaches.

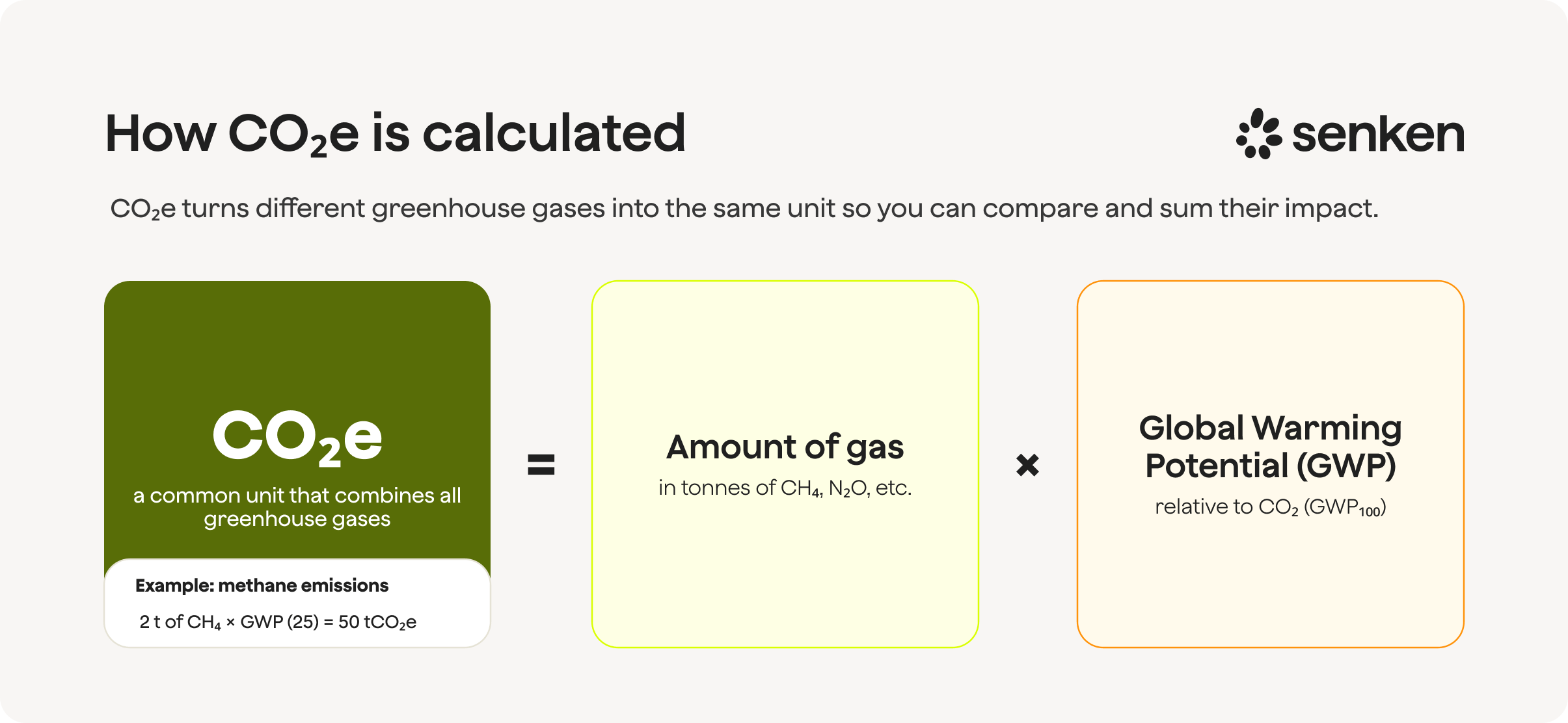

How CO2e is calculated: global warming potential (GWP) in practice

What is global warming potential (GWP100)?

Global warming potential is the scientific mechanism that converts each gas into CO2e. GWP measures the time-integrated radiative forcing of 1 kg of a gas relative to 1 kg of CO2 over a chosen time horizon. The 100-year horizon (GWP100) is the global standard for climate policy and corporate reporting, balancing short-lived and long-lived gases into a single comparable metric.

%2520by%2520gas-min.png)

The IPCC publishes GWP values in each Assessment Report. Most frameworks (GHG Protocol, SBTi, CSRD) now expect you to use AR5 or AR6 values. Here's a compact reference table for the gases you'll actually see in corporate inventories:

The CO2e formula and standard units

The core formula is straightforward:

CO2e = mass of gas × GWP

Your emission factor database may already express factors in CO2e (e.g., "0.233 kg CO2e per kWh"), which means the GWP conversion is baked in. For direct releases of non-CO2 gases (refrigerant leaks, process emissions), you multiply the mass by the GWP yourself.

Worked examples from a corporate inventory

Example 1: Refrigerant leak

Your facility reports a leak of 5 kg of HFC-134a from a chiller. Using AR6, HFC-134a has a GWP of 1,526.

CO2e = 5 kg × 1,526 = 7,630 kg CO2e = 7.63 tCO2e (Scope 1).

Example 2: Diesel in company fleet

You burn 10,000 litres of diesel. The emission factor is approximately 2.68 kg CO2e per litre (includes combustion CO2, CH4, and N2O already weighted).

CO2e = 10,000 L × 2.68 kg CO2e/L = 26,800 kg CO2e = 26.8 tCO2e (Scope 1).

Example 3: Purchased electricity

You purchase 100 MWh of grid electricity. Your location-based grid factor is 0.350 tCO2e/MWh.

CO2e = 100 MWh × 0.350 = 35 tCO2e (Scope 2, location-based).

Common errors to avoid: Mixing kg and tonnes (1 tCO2e = 1,000 kg CO2e). Double-counting GWP when your emission factor is already in CO2e. Using outdated GWP values from different IPCC reports across your inventory.

Using CO2e across Scope 1, 2, and 3 – and what GHG Protocol, CSRD, SBTi, EU ETS, and CBAM expect

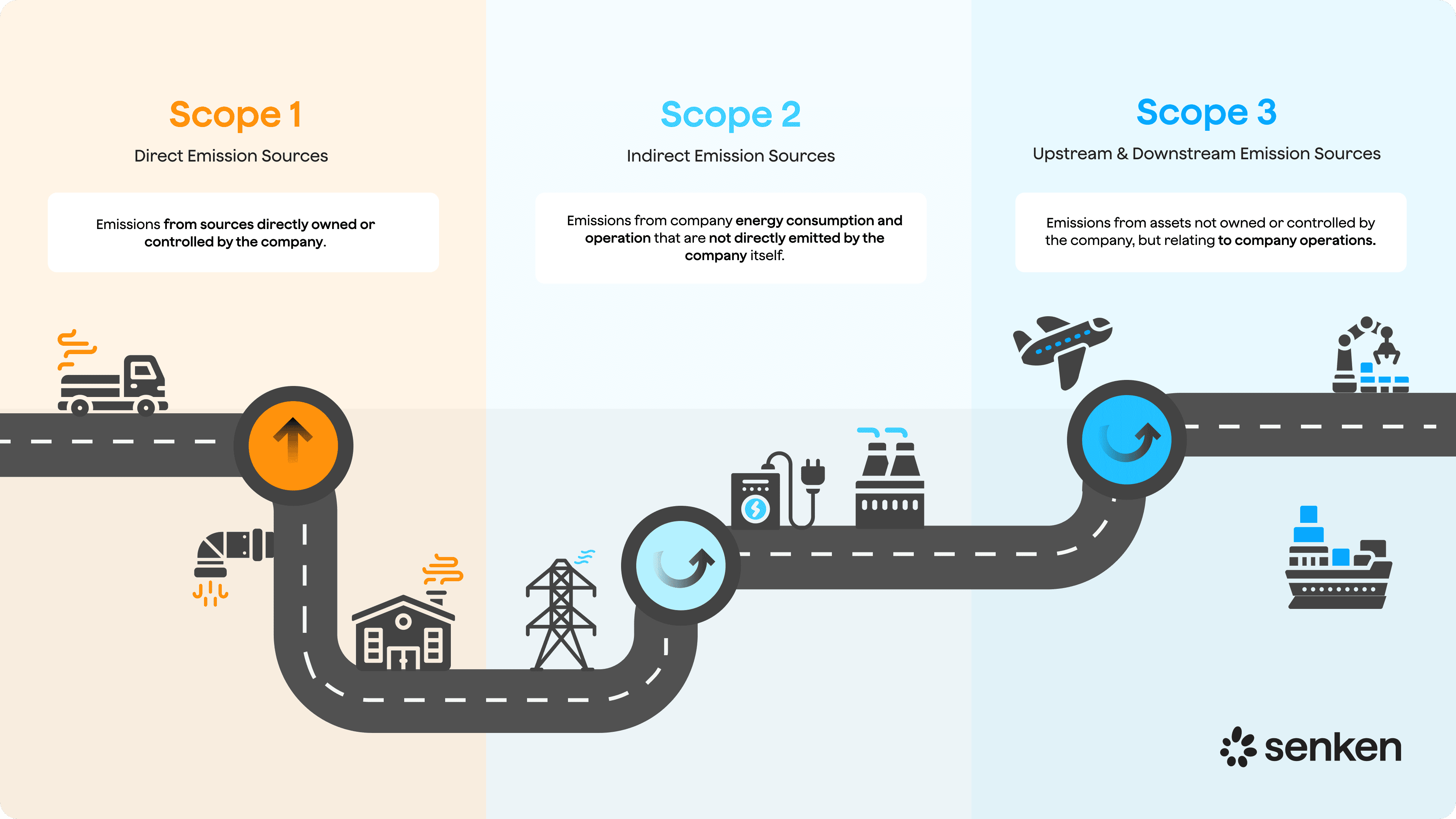

Building a consistent Scope 1, 2, 3 inventory in CO2e

Scope 1 (direct emissions): Fuel combustion, process emissions, refrigerant leaks. Calculate using activity data (litres, kg, MWh of fuel) and emission factors in tCO2e.

Scope 2 (purchased energy): Electricity, steam, heating, cooling. Report both location-based (grid average) and market-based (supplier-specific or certificates) in tCO2e. CSRD requires both.

Scope 3 (value chain): Purchased goods, transport, waste, business travel, employee commuting, use of sold products. Use a data hierarchy:

- Activity-based (primary data from suppliers)

- Supplier-specific emission factors

- Spend-based (€ spent × sector average factor)

Centralise your emission factor library in a single source of truth, versioned and expressed consistently in tCO2e. This prevents different business units or geographies from using conflicting factors.

Aligning with GHG Protocol, CSRD/ESRS E1, and SBTi

GHG Protocol: Covers the seven Kyoto gases using GWP100. You must document your chosen IPCC report version, organisational and operational boundaries, and calculation methodologies in a publicly available inventory report.

CSRD/ESRS E1: Requires disclosure of gross Scope 1, Scope 2 (location- and market-based), Scope 3, and total GHG emissions in tCO2e. Emissions must be verified to limited or reasonable assurance. Your methodology note should reference GWP sources, boundary definitions, and how you handle changes year-on-year.

SBTi: Expects GWP100 from AR5 or later for target setting. You must set near-term (5–10 year) and long-term (to 2050) absolute reduction targets in tCO2e, covering at least 95% of Scope 1 and 2 and the most material Scope 3 categories. Documentation of inventory boundaries and methods is mandatory for validation.

Checklist for auditors:

- GWP source documented (e.g., "IPCC AR6 GWP100")

- Scopes reported in tCO2e with clear boundaries

- Activity data and emission factors traceable

- Methodology changes logged and explained

- Evidence for any neutralisation claims (carbon credits)

Methodological choices and limitations: making your CO2e numbers robust and explainable

Choosing GWP timeframes and IPCC versions (AR4, AR5, AR6)

For corporate inventories, use GWP100 and document whether you follow AR5 or AR6. GHG Protocol allows either; SBTi requires AR5 or later; CSRD/ESRS E1 expects the latest IPCC at the time of reporting (currently AR6). If you transition from AR5 to AR6 mid-period, note the change and quantify the impact separately from real reductions.

GWP20 vs GWP100: GWP20 emphasises the near-term impact of short-lived gases like methane (GWP20 for fossil CH4 is ~80 vs GWP100 of 30). Some climate scientists argue GWP20 better reflects urgency. However, UNFCCC, GHG Protocol, and corporate standards converge on GWP100 for comparability. If you face pressure to report methane separately, you can supplement your disclosure with a GWP20 sensitivity analysis, but your primary inventory should remain GWP100.

What CO2e does not tell you

CO2e collapses different time dynamics into a single number. A tonne of methane (short-lived, high near-term warming) and a tonne of CO2 (long-lived, lower per-kg impact but persistent) both become CO2e, but their climate effects differ over time. CO2e also doesn't cover all climate forcers (black carbon, tropospheric ozone) and says nothing about co-benefits, biodiversity, or social impact.

Practical implication: Use CO2e as your primary metric for targets and reporting, but layer in narrative context. When you reduce methane, explain the near-term climate benefit. When you invest in nature-based removals, highlight permanence and co-benefits beyond the tCO2e number.

How to communicate methodology changes internally

When you update GWP values or emission factors, your reported emissions may jump or fall without any real change in operations. To manage this with your board and finance:

- Maintain a change log in your methodology note: "In 2026, we transitioned from IPCC AR5 to AR6 GWP values, increasing reported Scope 1 emissions by 2.3% (450 tCO2e). This reflects improved science, not higher actual emissions."

- Report emissions on a like-for-like basis for trend analysis: recalculate prior years using the new methodology so leadership sees true performance.

- Keep a versioned factor library with effective dates so you can audit and explain any number.

CO2e and carbon credits: what one tonne of CO2e should mean in your climate strategy

How projects turn impacts into tCO2e and credits

Carbon credit projects quantify their emissions reductions or removals in tCO2e through a multi-step process: establish a baseline (what would have happened without the project), demonstrate additionality (the project wouldn't happen otherwise), measure the impact (via monitoring, reporting, and verification or MRV), and issue credits (typically 1 credit = 1 tCO2e reduced or removed). A third-party verifier audits the claims before a registry (Verra, Gold Standard, Puro.earth) issues serialised credits.

The quality of that tCO2e depends entirely on the robustness of the methodology, the MRV system, and oversight. Not all tCO2e from credits are equal.

Avoidance vs removal in CO2e terms

Avoidance credits prevent emissions that would otherwise occur (renewable energy displacing coal, forest conservation preventing deforestation). They deliver tCO2e avoided, but the counterfactual baseline is often debated.

Removal credits actively take CO2 out of the atmosphere (reforestation, biochar, direct air capture). They deliver tCO2e removed, which is more durable and aligns with long-term net zero (where residual emissions must be neutralised by removals, per SBTi).

For CSRD and SBTi compliance, prioritise removals for neutralisation claims. Avoidance credits can support broader climate finance goals (Beyond Value Chain Mitigation), but they don't offset your residual footprint in a science-based net zero framework.

.svg)