What is a carbon offset? In simple terms, a carbon offset is the use of a certified carbon credit, representing one tonne of CO₂ equivalent (tCO₂e) reduced or removed elsewhere, that you retire to compensate for your own emissions. It's a straightforward concept, but for a sustainability lead, the reality is far more complex.

Here's the critical distinction: a carbon credit is the tradable unit issued by a project and tracked in a registry. Once you purchase and retire that credit against a specific emission, it functions as a carbon offset. Think of credits as the instrument, offsets as how you use them.

Under CSRD and ESRS E1, how you account for and disclose offsets directly affects audit outcomes, board scrutiny, and regulatory compliance. Offsets sit at the intersection of strategy, procurement, finance, legal, and communications. Getting the definition wrong means getting the governance wrong.

How carbon offset projects and credits actually work

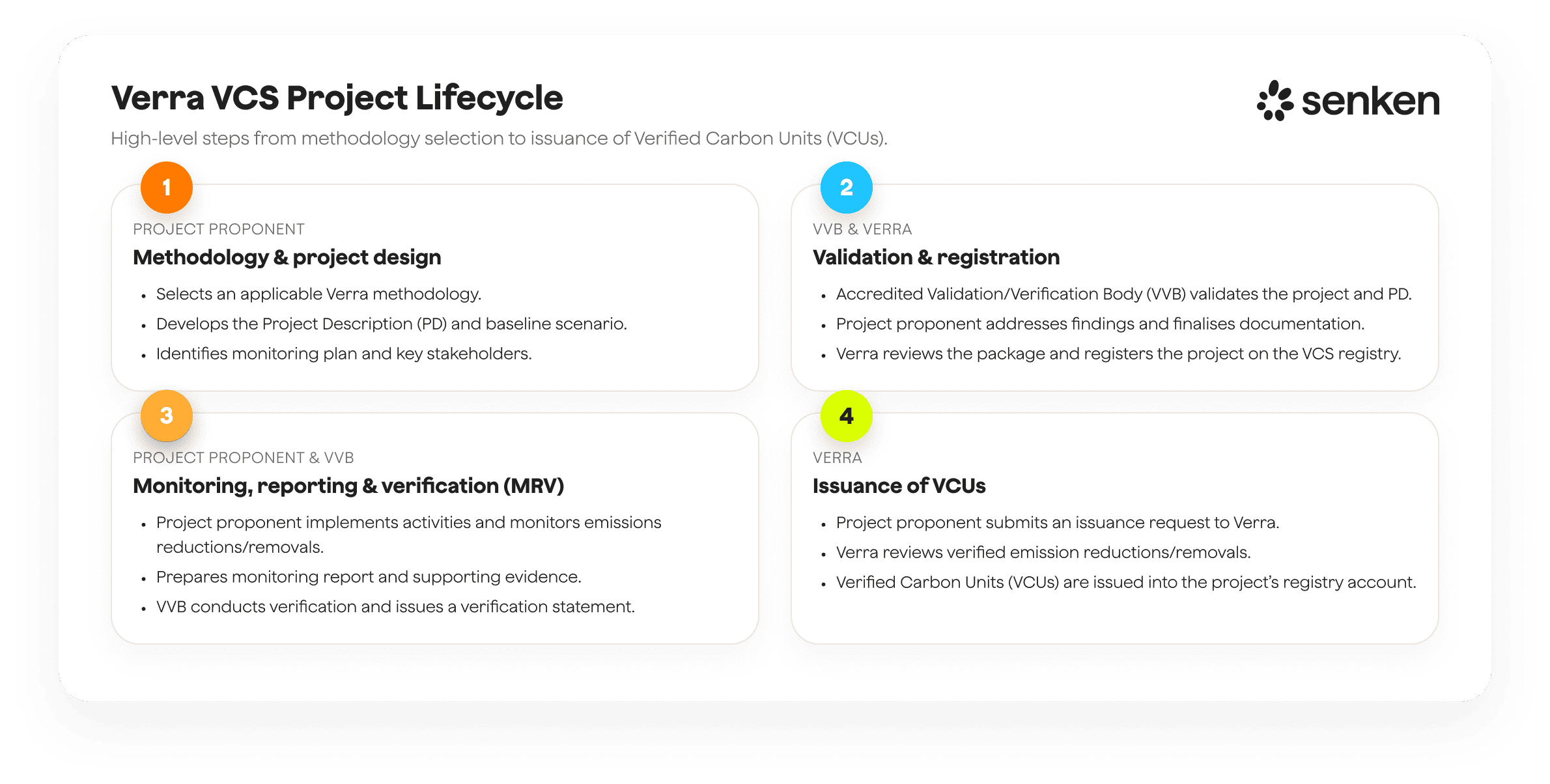

Carbon offset projects follow a structured lifecycle designed to ensure credibility, though the reality is far messier than the theory suggests.

Project design and baseline: A project developer identifies an activity that will reduce or remove emissions (e.g., reforestation, methane capture, renewable energy). They establish a baseline scenario showing what would have happened without the project. This baseline is the single biggest source of over-crediting risk. If the baseline assumes business-as-usual emissions that were never realistic, every credit issued is phantom impact.

Validation and verification: Independent third parties validate the project design and verify actual emissions reductions or removals against an approved methodology (e.g., Verra's VCS, Gold Standard). Verification happens periodically, typically annually. Look for projects with frequent monitoring and digital measurement, reporting, and verification (dMRV) using satellite or sensor data, not just developer self-reporting.

Issuance to a registry: Once verified, credits are issued to a public registry with unique serial numbers. Leading registries include Verra, Gold Standard, Puro.earth, and the American Carbon Registry. Each credit represents 1 tCO₂e and carries metadata: project ID, vintage year, methodology, and co-benefits.

Sale and retirement: You purchase credits from a project developer, broker, or marketplace. To use them as offsets, you must retire (permanently cancel) the credits in the registry, generating a retirement certificate. Only retired credits can be claimed against your emissions. Anything still in circulation is just inventory.

Every step is a potential control point. Ask your supplier for project design documents, verifier statements, monitoring reports, and retirement proofs. If they can't provide these within 48 hours, you're dealing with opacity, not quality.

Avoidance vs Removal – And Where Offsets Belong in a Net Zero Plan

Two types of offsets: avoiding vs removing emissions

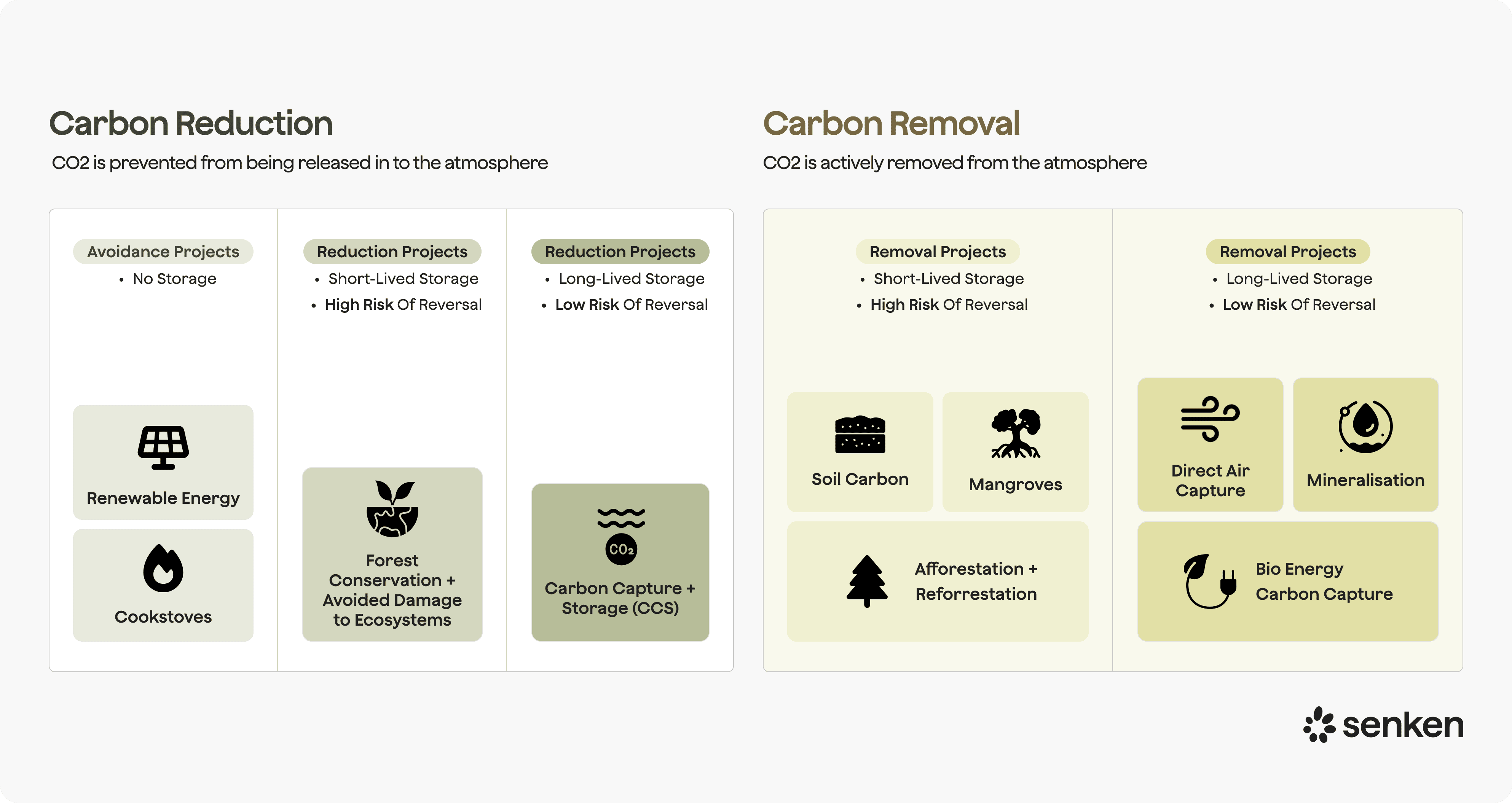

Avoidance credits prevent emissions that would otherwise occur. Examples include renewable energy displacing fossil generation, methane capture from landfills or agriculture, improved cookstoves replacing wood-burning, and REDD+ projects protecting forests from deforestation. These projects can deliver real climate value, but they face a structural problem: proving additionality. Would the activity have happened anyway due to regulation, economics, or social trends? Many legacy renewable energy and cookstove credits have been found to overstate impact by factors of 2x to 10x.

Removal credits physically extract CO₂ from the atmosphere and store it. Nature-based removals include afforestation and reforestation (ARR), soil carbon sequestration, and blue carbon (mangroves, seagrass). Technology-based removals include biochar, enhanced rock weathering, direct air capture with storage (DACCS), and bioenergy with carbon capture (BECCS). Removals differ dramatically in durability: nature-based storage typically lasts less than 100 years and faces reversal risks (fire, disease, land-use change), while engineered removals can sequester CO₂ for 1,000+ years.

For a net-zero strategy aligned with climate science, durability is non-negotiable. The Oxford Offsetting Principles and SBTi Corporate Net-Zero Standard both emphasize the shift from avoidance to long-duration removals as companies approach their target year.

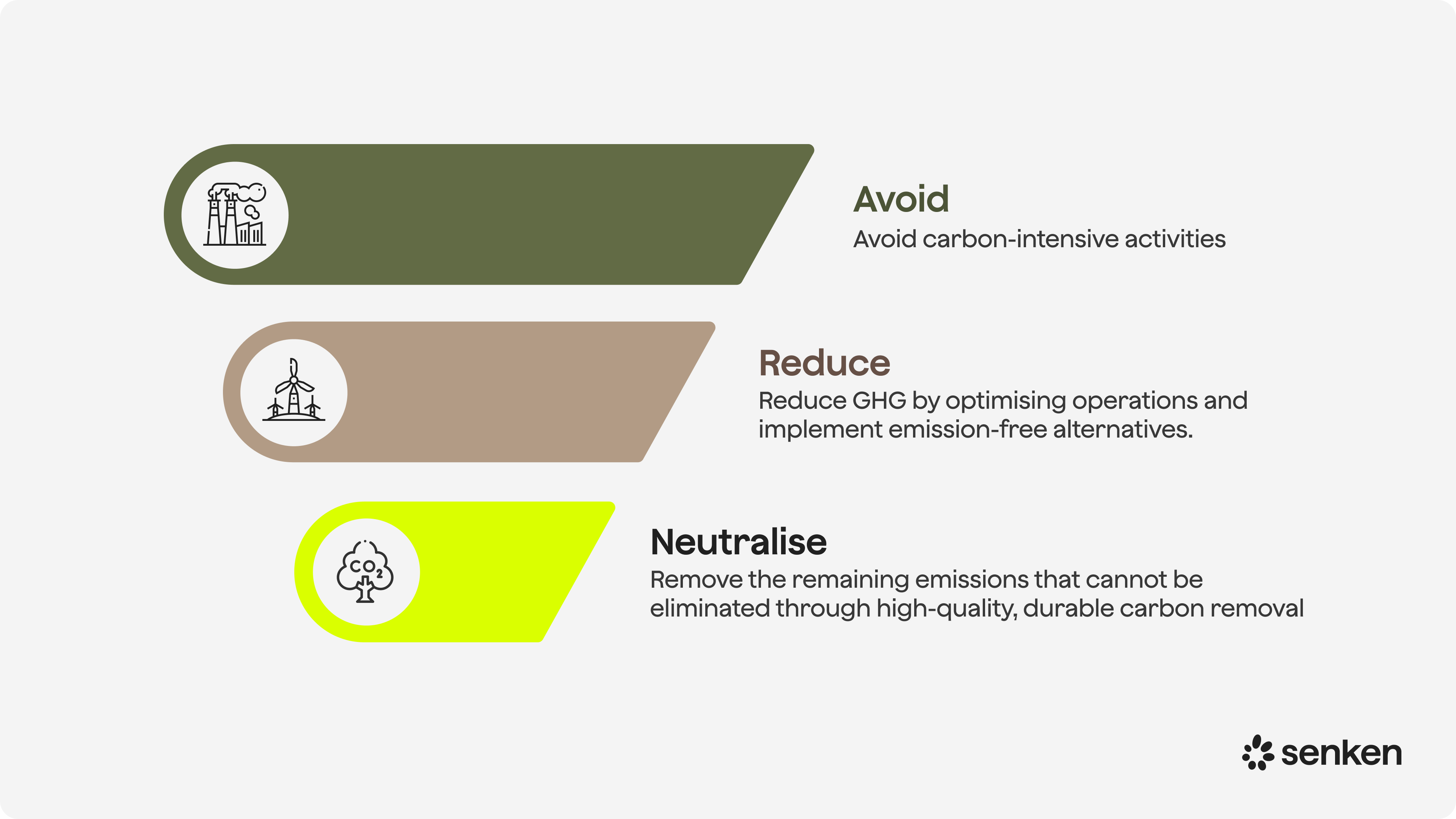

The mitigation hierarchy: avoid, reduce, then compensate

If you take one framework from this article into your next board presentation, make it this three-step hierarchy:

1. Avoid emissions where possible: Design out emissions at source through efficiency, circularity, modal shifts, and demand management. This is the highest-value action and the only one that reduces absolute emissions.

2. Reduce emissions across Scope 1, 2, and 3 in line with science-based targets: SBTi requires companies to cut emissions by over 90% across their value chain before claiming net zero. Offsets do not count toward these near-term or long-term reduction targets. Period. Your decarbonization roadmap must deliver these cuts through operational changes, renewable energy procurement, supplier engagement, and value chain transformation.

3. Compensate residual emissions with high-quality offsets: Only after steps 1 and 2 can you legitimately use offsets for the remaining <10% of emissions that are technically or economically infeasible to eliminate. These are true residual emissions, such as certain process emissions, long-haul aviation, or upstream categories where decarbonization options don't yet exist at scale.

Optionally, you can fund beyond-value-chain mitigation (BVCM) with additional offsets to accelerate the global transition, but BVCM is separate from your net-zero accounting. Document this clearly in your climate transition plan to avoid confusion with auditors.

As your SBTi net-zero year approaches (commonly 2040-2050), your offset portfolio should shift from short-lived avoidance credits to durable removals aligned with Oxford Principles. Start planning this transition now: high-quality removal supply is constrained, and prices are rising.

How Carbon Offsets Work Inside a Corporate: Roles, Rules, and Residual Emissions

In practice, offset decisions rarely sit with one person. Sustainability defines the principles and calculates residual emissions. Procurement runs RfPs, negotiates pricing, and manages supplier contracts. Finance treats credits as a line item with budget implications and price volatility risk. Legal and compliance review claims language and contracts for greenwashing exposure. Communications controls external messaging to avoid regulatory and reputational blowback.

Without clear governance, this fragmentation leads to misaligned incentives: procurement chases the cheapest credits, communications overstates impact, and sustainability is left defending decisions they didn't control.

Here's a lean governance model that works:

Internal offset policy: A 2-3 page document setting out your principles (mitigation hierarchy, no offsets for target compliance, phase-down plan for avoidance), eligible project types (e.g., only ICVCM-aligned or VCMI-compatible credits), minimum quality criteria (durability thresholds, external ratings, dMRV requirements), and red lines (e.g., no cookstoves, no pre-2015 renewable energy, no projects under legal dispute).

Approval thresholds and caps: Define who approves what. For example, sustainability can approve renewals up to €50k; finance and sustainability jointly approve new portfolios up to €250k; board approval required above €250k or for multi-year offtake agreements. Set annual caps on total volume (e.g., max 5% of gross Scope 1+2 emissions) and spend to prevent offsets becoming a substitute for real reductions.

Integration into reporting and assurance: Map offsets into your CSRD data model (ESRS E1-7 on carbon credits), IFRS S2 transition plan disclosures, and GHG inventory notes. Maintain an evidence folder per credit: retirement certificate, project design document, verifier statement, external rating, and proof of payment. Your auditor will ask for this. Have it ready.

Now, how do you define residual emissions in a way an auditor will accept? Start from your SBTi-aligned reduction pathway. Document which emission sources remain after applying all technically and economically feasible abatement levers. For example: "After electrifying our fleet, switching to SAF for 40% of air travel, and engaging top suppliers on Scope 3 reductions, we project 8,200 tCO₂e of residual emissions by 2040, comprising 60% process emissions from chemical reactions and 40% employee commuting in rural locations without public transport alternatives.

Ring-fence these tonnes separately in your GHG inventory and transition plan. Show the calculation. This is what offsets can legitimately address, and only with high-integrity removals as you near net zero.

How to Judge Carbon Offset Quality And Avoid Greenwashing

Five pillars of integrity you should hard-code into your policy

Translate these classic integrity criteria into policy-ready language your procurement team can operationalize:

Additionality: Would the emissions reductions or removals have occurred without carbon finance? Look for projects that face genuine financial, technological, or regulatory barriers. Red flag: renewable energy projects in countries with strong feed-in tariffs or grid mandates. These would have been built anyway.

Permanence and reversal risk: How long is the carbon stored, and what happens if it's released? For nature-based projects, check buffer pool contributions (typically 10-40% of credits withheld to cover reversals) and monitoring frequency. For engineered removals, demand evidence of geological or material stability. Avoid projects with vague "permanence" claims and no insurance mechanism.

Leakage: Does the project simply shift emissions elsewhere? Classic example: protecting one forest area while logging pressure moves to an adjacent unprotected area. Look for projects with wide geographic boundaries and third-party leakage assessments.

Independent verification: Who verified the reductions, when, and under what standard? Insist on third-party verifiers accredited under ISO 14065. Avoid projects verified only by the developer or where the last verification is more than 24 months old.

No double counting: Is anyone else claiming the same emission reduction? Check for corresponding adjustments under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement if the project is in a country with a national emissions target. Ensure the credit has been retired in your name, with a unique serial number.

Beyond the core five, assess co-benefits (SDG contributions, biodiversity, community livelihoods) and governance (benefit-sharing mechanisms, free prior informed consent for indigenous communities, transparent financial flows).

.svg)