What Are Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) – In Plain Corporate Language?

Shared socioeconomic pathways are the globally recognised narratives that describe how society, technology, energy systems and policy could evolve through this century. They're not predictions, they're plausible futures built on different assumptions about population growth, economic development, energy mix, technology adoption and governance. When you see scenario labels like SSP1-2.6 or SSP5-8.5 in IPCC reports or your consultant's climate risk deck, that's an SSP narrative combined with a specific level of radiative forcing (the number after the dash). These combinations give you a complete climate scenario.

Here's what matters for your work: SSPs assume no new climate policy by default, so they serve as reference pathways. Climate modellers then layer on mitigation policies to hit different temperature targets, creating the scenarios regulators, banks and standard setters expect you to use in climate risk and net-zero planning.

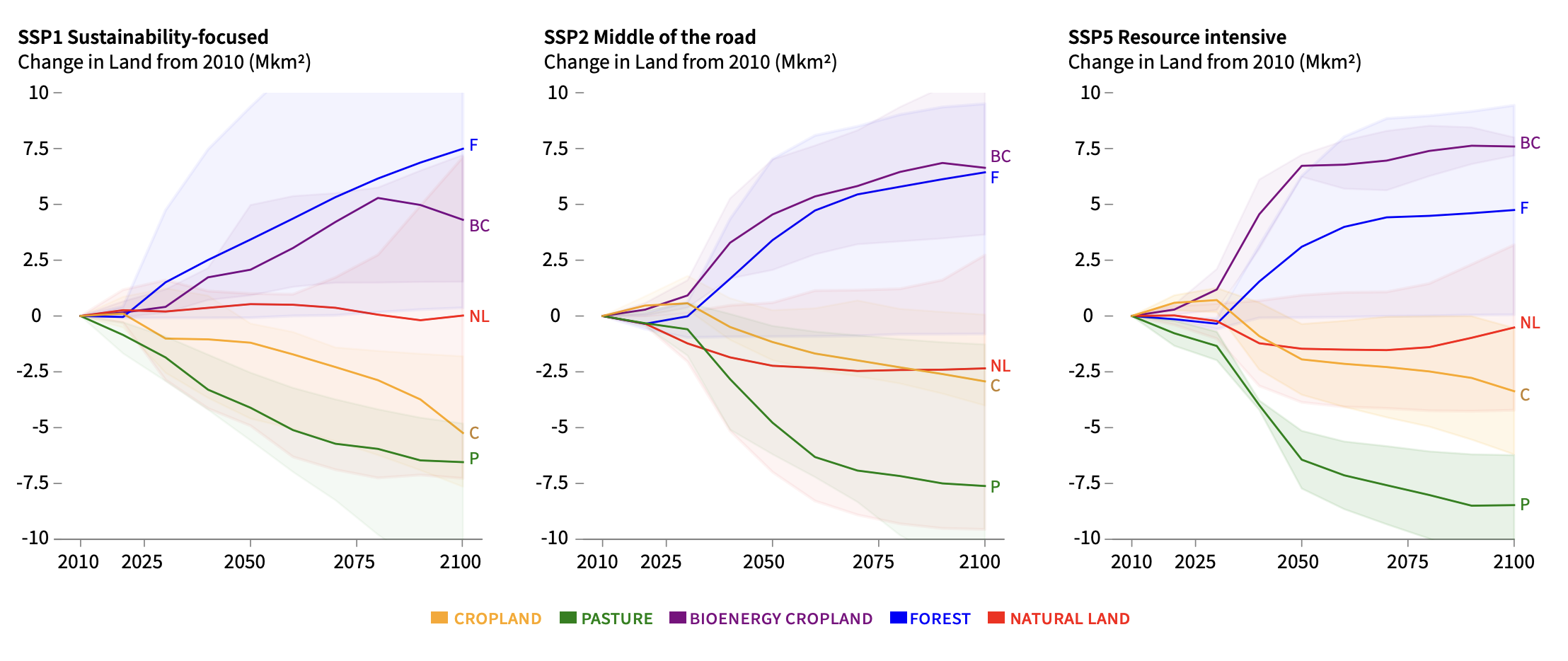

There are five core SSPs, each representing a different world. SSP1 (Sustainability) describes rapid clean technology adoption, strong international cooperation and low inequality, making both mitigation and adaptation relatively straightforward. SSP2 (Middle of the Road) is a continuation of current trends with moderate challenges. SSP3 (Regional Rivalry) depicts a fragmented world with weak governance, high conflict and severe barriers to both cutting emissions and adapting. SSP4 (Inequality) combines high-tech mitigation in wealthy regions with deep adaptation challenges for the rest. SSP5 (Fossil-Fueled Development) envisions rapid economic growth powered by fossil energy, making mitigation extremely difficult but leaving rich countries able to adapt through technology.

How SSP Scenarios Underpin Climate Risk, CSRD and Investor Expectations

If you're preparing CSRD disclosures or responding to ISSB/IFRS S2 expectations, you've probably been told to use "Paris-aligned scenarios" and demonstrate climate resilience. The practical reality is that most mainstream scenario tools, NGFS pathways, WBCSD frameworks and consultant models are built on SSPs. When your auditor or investor asks whether your scenarios are credible and consistent with IPCC science, they're checking whether you're anchored in this shared architecture.

CSRD requires you to disclose the scenarios you've used, whether they're Paris-aligned, and how the outcomes inform your strategy and resilience. ISSB's climate standard expects scenario analysis using recognised "off-the-shelf" pathways, which in practice means IPCC- or NGFS-derived scenarios rooted in SSPs. Research shows that 76% of large publicly traded companies already use SSPs or the older RCP scenarios in their climate adaptation planning, so you're working within an established practice.

What does this mean in concrete terms? SSP-based scenarios let you translate abstract climate futures into the risk drivers your board cares about. On the transition risk side, different SSPs give you ranges for carbon prices (from negligible in SSP3/SSP5 baseline worlds to €50-€100+ per tonne CO₂ in SSP1-type 1.5°C pathways by 2030), technology costs, stranded asset exposure and regulatory stringency. On the physical risk side, SSP2-4.5 projections show that extreme heat, water stress and drought could cost S&P 1200 companies around $885 billion annually in the 2030s, rising to $1.2 trillion in the 2050s. Coastal flooding costs escalate nearly 14-fold from the 2050s to 2090s under the same scenario. For sectors like telecoms and manufacturing with energy-intensive, geographically fixed assets, these numbers are material.

The safest approach is to align with SSP-based pathways rather than inventing bespoke scenarios. Your auditors know them, your bank's risk team uses them, and your sustainability report will stand up to scrutiny when regulators tighten disclosure rules in the next cycle.

.svg)