The Paris Agreement is a legally binding international treaty on climate change, adopted by 195 countries at COP21 in Paris on 12 December 2015 and entering into force on 4 November 2016 . Today, nearly every country in the world is a Party to the Agreement, making it the most comprehensive global framework for climate action.

For corporate sustainability leaders, the Paris Agreement is not just a diplomatic milestone. It is the foundation for the regulations your company faces today: CSRD, EU Taxonomy, CSDDD, EU ETS, and CBAM all draw their ambition and timelines directly from Paris. When your auditors ask whether your climate targets are "credible" or your board questions your carbon credit strategy, they are implicitly judging you against Paris benchmarks.

The Agreement's central goal is to hold the increase in global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the increase to 1.5 °C . This temperature target is not aspirational rhetoric. It translates into hard emission reduction requirements that shape investor expectations, regulatory timelines, and the criteria for "Paris-aligned" corporate strategies.

The 1.5 °C goal and what it implies for global emissions

To limit warming to 1.5 °C with no or limited overshoot, global net anthropogenic CO₂ emissions must decline by about 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 and reach net zero around 2050 . For comparison, a 2 °C pathway requires roughly 25% cuts by 2030 and net zero around 2070. This is why the difference between "well below 2 °C" and "1.5 °C" matters operationally: the pace of decarbonisation over the next five to seven years is dramatically steeper under 1.5 °C scenarios.

For large companies, this means that any net-zero commitment calling itself Paris-aligned must demonstrate interim reductions that track close to this 45% cut by 2030. Many corporate targets today still reference 2 °C pathways or legacy baselines, which are no longer considered credible by investors or rating agencies. If your 2030 target was set using a 2 °C sectoral pathway, there is a strong likelihood you will face pressure to revise upward.

The practical implication: when you design science-based targets, your internal carbon budget, or your transition plan, the 1.5 °C pathway from the IPCC provides the North Star. Every major EU climate regulation, from the Climate Law to CSRD, now embeds this trajectory as the reference scenario for compliance and disclosure.

From Paris to Your Balance Sheet: How the Treaty Shows Up in EU & Rules

Paris, EU Climate Law and why 2030/2050 targets matter for you

The Paris Agreement operates on a five-year "ratchet" cycle, where countries submit Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) starting in 2020, with each successive NDC intended to reflect higher ambition . The EU translated its Paris commitment into legally binding domestic legislation through the European Climate Law, which commits the Union to climate neutrality by 2050 and at least a 55% net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 compared to 1990 levels.

Why does this matter for your company? Because every major piece of EU sustainability regulation you face takes these 2030 and 2050 targets as its baseline. Your CSRD climate disclosures must show how your transition plan aligns with limiting warming to 1.5 °C. Your EU Taxonomy eligibility hinges on whether your activities are consistent with the Paris Agreement's long-term temperature goal. Your supply chain due diligence under CSDDD explicitly references the 1.5 °C objective. In short, Paris is no longer a policy abstraction. It is hardwired into your audit questions, capital allocation decisions, and legal compliance obligations.

CSRD, EU Taxonomy, CSDDD, EU ETS and CBAM in one simple map

Here is how the chain works in practice:

-white.png)

CSRD (Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive): CSRD entered into force on 5 January 2023 and requires all large companies and listed entities to report on sustainability, with phased application starting from financial years beginning 1 January 2024 . Your ESRS E1 climate disclosures must include transition plans that demonstrate consistency with limiting warming to 1.5 °C. Auditors will ask how your 2030 targets, capex plans, and carbon credit use support this trajectory.

EU Taxonomy: Regulation (EU) 2020/852 establishes criteria for environmentally sustainable economic activities, and an activity pursuing climate change mitigation must be consistent with the long-term temperature goal of the Paris Agreement . If you want to label investments or products as Taxonomy-aligned, you must prove they support a 1.5 °C pathway.

CSDDD (Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive): Adopted in June 2024, CSDDD requires large companies to integrate due diligence for human rights and environmental impacts across value chains, with explicit reference to the Paris Agreement's 1.5 °C goal . This means your Scope 3 suppliers will need to demonstrate credible climate plans, and you will be legally accountable for that alignment.

EU ETS and CBAM: The EU ETS linear reduction factor was increased to 4.3% per year for 2024–2027 and 4.4% from 2028, targeting a 62% reduction by 2030 relative to 2005 . CBAM applies carbon pricing to imports of carbon-intensive goods, entered into force in May 2023, and moves to full certificate surrender obligations from January 2026 . Both mechanisms directly reflect the EU's Paris-aligned trajectory and translate it into hard costs for your operations and supply chain.

Practical checklist for sustainability leaders:

- Which regulations hit your company first? (Typically CSRD, then Taxonomy, CBAM, and CSDDD depending on size, sector, and supply chain complexity.)

- Who internally owns each piece? (Finance for CSRD/Taxonomy, procurement for CSDDD, operations for ETS/CBAM.)

- Are your current targets and transition plan sufficient to pass CSRD audit and investor scrutiny under these rules?

Designing a Paris-Aligned Corporate Climate Strategy

Turning 1.5 °C pathways into science-based corporate targets

Building a Paris-aligned strategy is not about aspirational statements. It is about translating global carbon budgets into company-specific reduction roadmaps that can be defended in front of auditors, investors, and regulators. Here is a simple five-step process:

1. Map your footprint and main emitting activities: Start with a robust, auditable GHG inventory covering Scopes 1, 2, and material Scope 3 categories. Identify your largest emission sources and ensure your baseline year data is solid.

2. Benchmark against 1.5 °C sector pathways: Use frameworks like the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) sector guidance or IEA Net Zero sectoral roadmaps to understand what decarbonisation looks like in your industry. SBTi provides sector-specific methods that translate the global 1.5 °C carbon budget into company-level targets.

3. Set near-term (2030) and net-zero targets that reflect Paris pathways: Your near-term target should demonstrate you are on track for roughly 45% CO₂ reductions by 2030 (from a 2010 or equivalent baseline). Your long-term target should commit to net-zero CO₂ around 2050, with clarity on what "residual" emissions remain and how they will be addressed. Many companies make the mistake of setting only a 2050 net-zero goal without credible 2030 interim milestones. Investors and regulators now demand both.

4. Define an internal carbon budget and milestones: A carbon budget translates your trajectory into cumulative tonnes of CO₂e you can emit between now and net zero. Break this into five-year increments (2025–2030, 2030–2035, etc.) and assign accountability at the business-unit or asset level. This makes decarbonisation tangible for your CFO and operations teams.

5. Integrate into governance, capex planning, and procurement: Paris alignment must move beyond the sustainability report. Embed it in your board's risk oversight, link climate KPIs to executive compensation, and build Paris-consistent criteria into your capex approval process and supplier selection. For example, use an internal carbon price that reflects the trajectory of EU ETS and CBAM costs, and require major capital projects to demonstrate alignment with your 2030 carbon budget.

%2520(light).png)

Governance, capex and supplier strategy under a Paris lens

Here are three concrete questions you can use to test whether your strategy is truly Paris-aligned or just "policy-compliant":

Question for your CFO: "Are our interim targets Paris-consistent (tracking toward 45% cuts by 2030 and net zero around 2050), or are they simply aligned with current national policy, which may be below a 1.5 °C trajectory?" The difference matters, because current NDCs and policies still fall short of Paris goals, and leading investors benchmark you directly against 1.5 °C scenarios.

Question for your COO: "How much of our planned capex over the next three to five years is Paris-aligned, meaning it supports activities consistent with 1.5 °C or is spent on decarbonisation, adaptation, or enabling infrastructure?" Many companies discover that the majority of their capex still locks in high-carbon assets or business-as-usual operations, which will strand or require write-downs as regulation tightens.

Question for your procurement lead: "Do we have an internal carbon price that reflects EU ETS and CBAM trajectories, and are we using it to steer supplier decisions and contract negotiations?" If your procurement decisions ignore the rising cost of carbon embedded in goods and services, you are not pricing in Paris-aligned risk and will face margin pressure as CBAM and value-chain due diligence obligations kick in.

Paris Agreement, Article 6 and Carbon Credits: Using Markets Without Greenwashing

What Article 6 actually changes for corporate offsetting

Article 6.2 of the Paris Agreement provides guidance for countries to engage in cooperative approaches, allowing the use of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (ITMOs) toward their NDCs, subject to robust accounting and corresponding adjustments to avoid double counting . Article 6.4 establishes a UN-supervised mechanism to issue mitigation contribution units for activities that achieve additional, measurable, and permanent GHG emission reductions or removals, with a 2% share of proceeds going to the Adaptation Fund and a requirement for overall mitigation in global emissions .

.png)

In plain terms: Article 6 is the Paris rulebook for carbon markets. The key changes for corporate buyers are:

Corresponding adjustments: When a credit is transferred internationally and used by a company or another country toward their target, the host country must adjust its national emissions inventory to avoid counting the same tonne of CO₂ twice. This prevents the "double counting" problem that plagued older carbon markets. For voluntary corporate buyers, this means credits issued under Article 6 frameworks (or that voluntarily apply corresponding adjustments) are higher integrity and lower legal risk.

Overall mitigation in global emissions: Article 6.4 credits must contribute to an overall decrease in global emissions, not just a transfer from one actor to another. This raises the bar on additionality and baseline conservatism. Credits that simply shift emissions around, or that use inflated baselines, will not meet this standard.

Stricter transparency and verification: Both Article 6.2 and 6.4 require robust reporting and third-party verification under UNFCCC rules. Even though most corporate purchases today happen in voluntary markets outside Article 6, the integrity expectations set by Article 6 are rapidly becoming the benchmark that auditors, investors, and regulators use to judge all carbon credits.

For companies under CSRD, the practical implication is clear: if you are using carbon credits to claim "carbon neutrality" or to address residual emissions in your net-zero plan, you will need documentation that demonstrates the credits meet Article 6-grade integrity standards. Low-quality credits that cannot demonstrate robust additionality, permanence, and no double counting are now a compliance and reputational risk.

A practical framework for 'Paris-aligned' carbon credit use

Here is a clear, implementable hierarchy for corporates navigating carbon credits under a Paris lens:

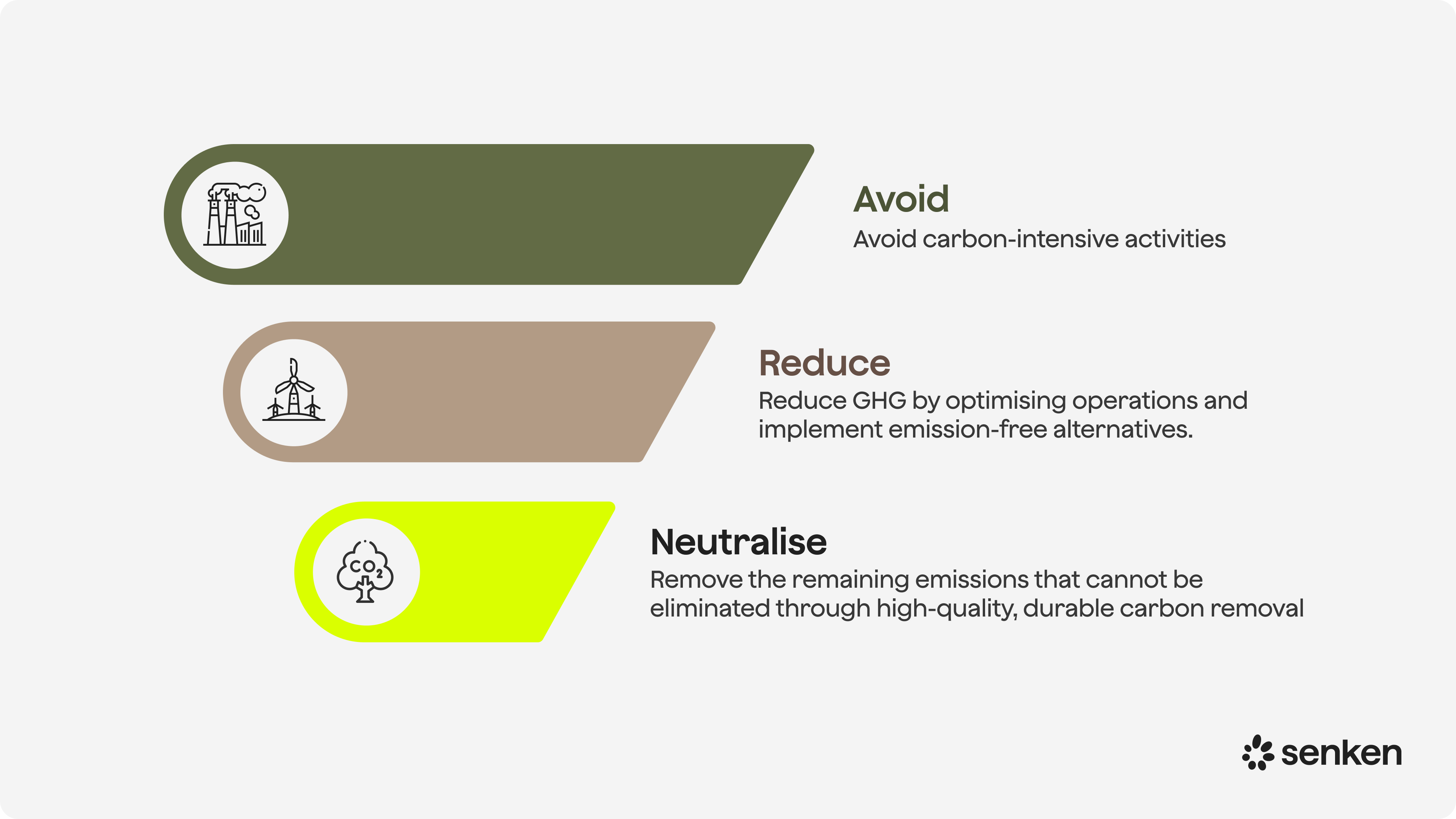

1. Maximise internal abatement in line with 1.5 °C: Carbon credits are not a substitute for deep decarbonisation. Your first priority is reducing your own emissions at the pace required by a 1.5 °C pathway (roughly 45% by 2030). Only after you have exhausted cost-effective internal abatement should you turn to credits to address residual emissions.

2. Define residual emissions transparently: Be explicit about what emissions you classify as "residual" (typically hard-to-abate Scope 1 and unavoidable Scope 3). Many companies over-classify emissions as residual to justify continued offsetting. Under CSRD, you will need to defend this classification to auditors.

3. Use only high-integrity credits that meet robust criteria: The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market's Core Carbon Principles define ten criteria for high-quality carbon credits, including additionality, permanence, robust quantification, no double counting, and compatibility with net-zero pathways aligned to 1.5 °C . In practice, this means:

- Additionality: The project would not have happened without carbon finance.

- Permanence: Carbon storage is durable (multi-century for removals or protected against reversal).

- Conservative baselines: Emission reductions are calculated against realistic counterfactuals, not inflated reference scenarios.

- No double counting: Credits come with corresponding adjustments or are issued under frameworks that prevent multiple claims.

- CSRD-ready documentation: You have transparent, auditable evidence packs for every credit, including third-party verification reports, project monitoring data, and alignment with ICVCM or equivalent standards.

Senken's Sustainability Integrity Index operationalises these filters in practice, evaluating projects across more than 600 data points covering carbon impact, beyond-carbon co-benefits, MRV processes, and compliance. With a project acceptance rate below 5%, the SII ensures only the highest-quality credits—those that can withstand CSRD audits and Article 6-informed scrutiny—enter client portfolios. For example, Vodafone Germany used the SII framework to build an Oxford-aligned removals portfolio that neutralised residual Scope 1 and 2 emissions while avoiding greenwashing risk and simplifying audits with ready-to-use evidence packs.

Is the Paris Agreement Working – and How Should Companies React?

The short answer: global progress is real but insufficient. As of mid-2025, 12,353 companies worldwide have set or committed to science-based targets, with 9,764 validated targets and 2,325 net-zero targets . Nearly two-thirds (63%) of the Forbes Global 2000 have net-zero targets, covering over $36 trillion in annual revenue . However, analysis of 51 major global companies found average 2030 emissions reduction targets of 30%, below the ~43% reduction needed to limit warming to 1.5 °C, with many companies relying on offsets rather than robust abatement .

The Transition Pathway Initiative's 2024 report found 30% of the 409 largest corporate emitters have long-term (2050) targets aligned with 1.5 °C, up from 7% in 2020, but interim targets and clear strategy elements are often lacking . The Climate Action 100+ Net Zero Company Benchmark reported only 10% of focus companies have short-term (up to 2025) targets aligned with a 1.5 °C scenario covering all material emissions scopes .

In other words: many large companies have made net-zero pledges, but only a minority have credible, 1.5 °C-aligned short- and medium-term plans that cover all scopes. Current national policies and NDCs also remain insufficient; the world is not yet on track to meet the Paris temperature goals, and a significant ambition and implementation gap persists.

What this means for your company: "Minimum compliance" with today's national policies or EU regulations is below a Paris-aligned trajectory. Leading investors, rating agencies, and NGOs increasingly benchmark large DACH companies directly against 1.5 °C scenarios, not just the policy floor. If your strategy is to do only what regulation mandates today, you risk being classified as a laggard by investors using frameworks like the Transition Pathway Initiative, Climate Action 100+, or CDP A-list criteria.

The corporate implication is clear: you need to plan for faster decarbonisation than the policy floor. Companies that wait for regulation to force every step will face last-minute, high-cost transitions and stranded assets. Those that align proactively with 1.5 °C pathways can lock in cost advantages, secure access to high-quality carbon removals before supply tightens, and position themselves as climate leaders in their sectors.

.svg)