Hard to abate emissions are greenhouse gas emissions from sectors and processes—like steel, cement, chemicals, aviation, shipping, and heavy trucking—that require very high-temperature heat or generate process emissions, making them technically difficult and economically challenging to eliminate with today's low-carbon alternatives. These sectors are responsible for roughly 40% of global direct CO₂ emissions and sit at the core of many German, Austrian, and Swiss business models, from manufacturing and construction materials to logistics and heavy industry.

For sustainability managers, the real challenge isn't just understanding the term—it's using it as a management tool under CSRD, SBTi, and increasing assurance requirements. How do you classify which emissions genuinely qualify as hard to abate? What's the difference between hard to abate, unavoidable, and residual emissions? When is it credible to use carbon removal credits, and when does it cross into greenwashing?

This playbook gives you a concise, step-by-step approach: how to classify, prioritise, and decarbonise your hard to abate emissions—and, only for the residual slice that remains at net zero, how to credibly use high-integrity carbon removal credits that will stand up to auditors and regulators.

1. What are hard to abate emissions?

Defining hard to abate emissions in simple, science-aligned terms

Hard to abate emissions come from sectors and processes that depend on energy-intensive operations requiring high-temperature heat and generate process emissions that cannot be fully eliminated by fuel switching , making decarbonisation technically difficult and costly today. Think blast furnace steel, cement calcination, primary chemicals production, long-haul aviation, deep-sea shipping, and heavy-duty trucking. These aren't emissions you can electrify with a solar array or eliminate with a supplier switch next quarter.

The defining characteristics are clear: temperatures above 500 °C that current electric heating struggles to match economically, process emissions baked into the chemistry (like CO₂ released when limestone becomes clinker in cement), and dependence on energy-dense liquid fuels where batteries and hydrogen infrastructure aren't yet viable at scale. These hard-to-abate sectors collectively account for roughly 25% of global energy use and around 20% of total global CO₂ emissions , and still represent nearly 40% of global greenhouse gas emissions when you include all direct and indirect sources.

Where hard to abate emissions typically show up in large companies

For a DACH-headquartered manufacturer, these emissions sit in your own steelmaking or chemical plants (Scope 1), the steel and cement embedded in your products and buildings (Scope 3 upstream), the ships and trucks moving your goods internationally (Scope 3 logistics), and the flights your teams take (Scope 3 business travel). EU industry accounts for roughly 20% of the EU's GHG emissions, with steel and cement production responsible for approximately two-thirds of those industry emissions .

Even if you're a service company, hard to abate emissions likely dominate your Scope 3 footprint through purchased hardware, data centre construction materials, and freight. The key insight: these aren't edge cases. They're core to European and global value chains, which is why how you classify and manage them will make or break your net-zero credibility.

2. From hard to abate to residual: a simple emissions hierarchy you can defend to auditors

Hard to abate vs. unavoidable vs. residual emissions

Let's clear up three terms that get mixed up constantly. Hard to abate emissions today are those difficult to reduce right now due to current technology maturity, infrastructure gaps, and economics. Unavoidable emissions refer to GHG emissions that remain after all practical and economically viable reduction measures, intrinsically linked to operations where no zero-carbon alternative is available . Residual emissions are more specific: they are emissions still entering the atmosphere when net-zero is reached, remaining after all feasible abatement efforts have been applied, and must be counterbalanced by carbon dioxide removal .

Here's why the distinction matters: what's hard to abate today can be removed from that list as technologies scale. The classification of sectors as hard-to-abate can change as low-carbon technologies mature; for example, once green hydrogen DRI becomes cost-competitive, steel may shift from hard-to-abate to an abatable category. Your internal classifications need regular updates, or you risk labelling something "unavoidable" when a viable solution just reached commercial scale.

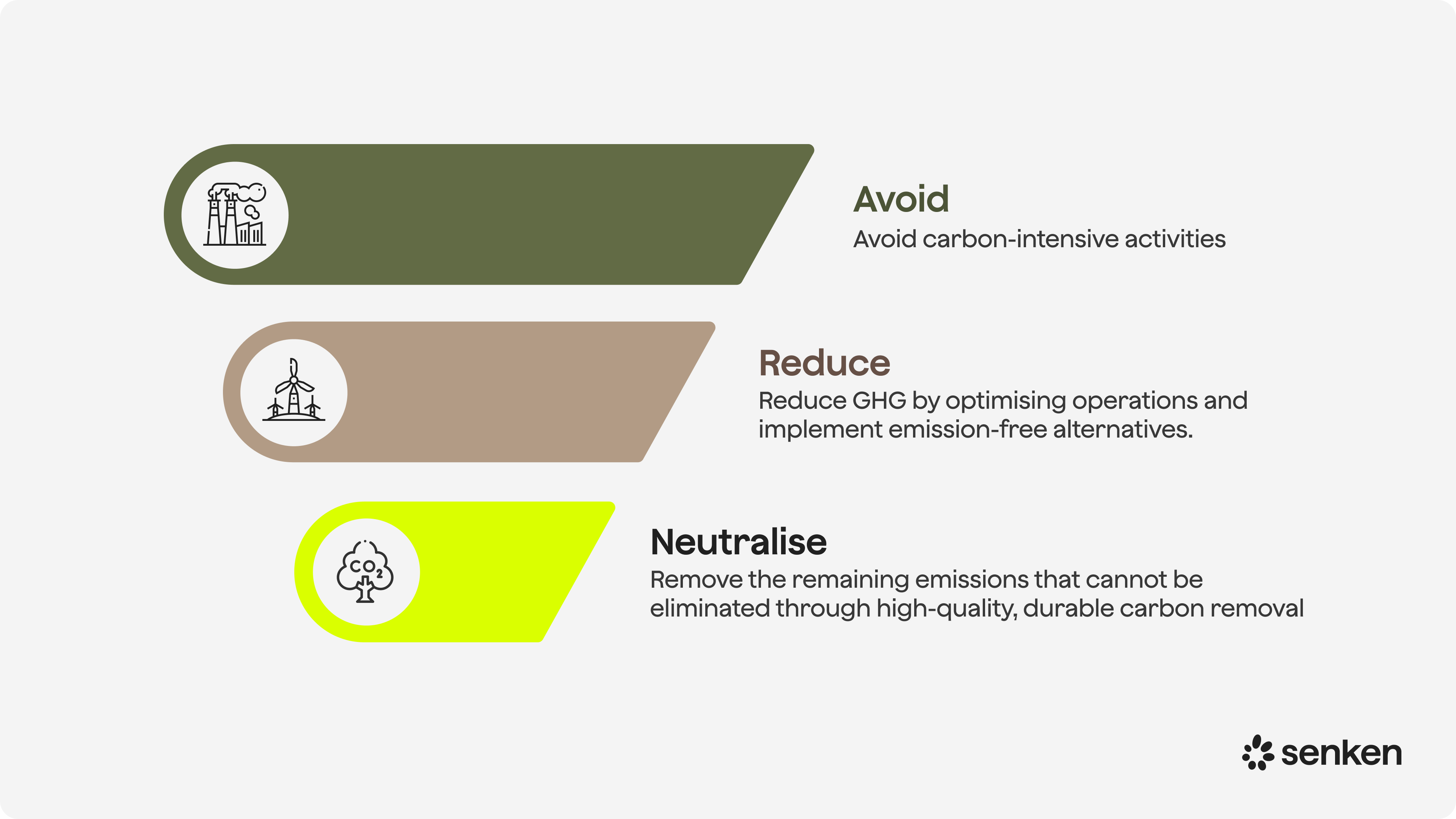

Connecting the hierarchy to your mitigation strategy

Apply a clear mitigation hierarchy: avoid emissions where possible, reduce through efficiency and fuel switching, substitute with low-carbon alternatives (green hydrogen, e-fuels), capture via CCUS where substitution isn't feasible, and finally neutralise true residual emissions with high-durability carbon removals. Each step should tie to a decision rule you can defend internally and to auditors. For example, classify an emission as hard to abate if no commercially available, cost-effective alternative exists that fits your asset renewal timeline. Review that classification every two to three years as policy and technology evolve.

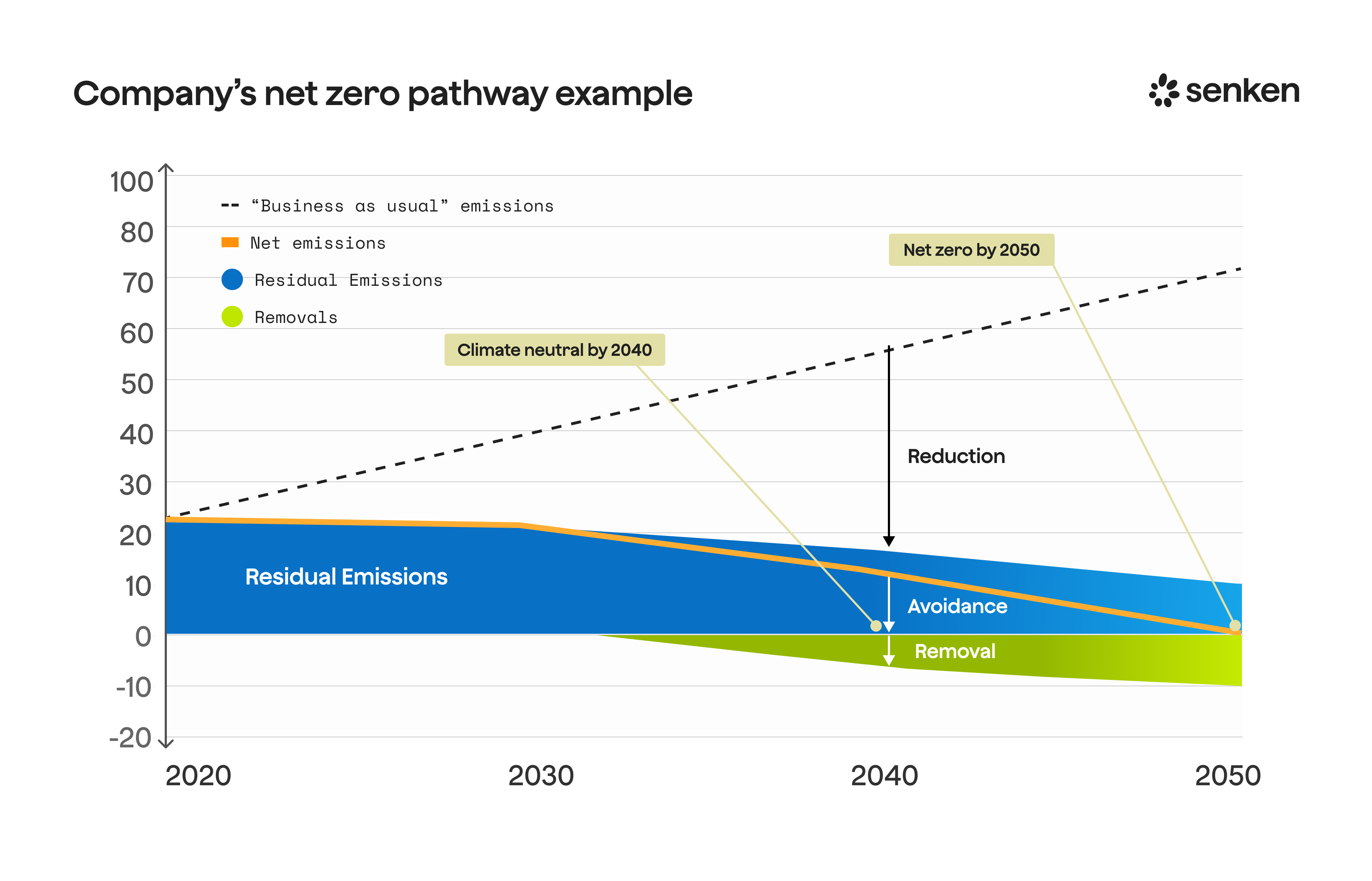

When setting your net-zero roadmap, map each hard-to-abate cluster to an expected abatement pathway and timeline. Be explicit: "We expect 70% abatement in this category by 2035 via electrification and supplier engagement; the remaining 30% will likely be residual and addressed via permanent removals." That transparency builds trust with stakeholders and simplifies your CSRD disclosures.

3. Step-by-step: mapping hard to abate emissions across your Scopes 1–3

Start with your existing GHG inventory and tag likely hard-to-abate categories. In Scope 1, flag any process heat above 500 °C, calcination, steam cracking for petrochemicals, or own heavy-duty vehicle fleets. In Scope 2, if you're pursuing electrification of high-temperature processes, note the massive electricity demand and grid decarbonisation dependency. In Scope 3, focus on purchased materials (steel, cement, aluminium, plastics, chemicals), international freight (aviation, shipping, heavy trucking), and, for some sectors, use-of-sold-products emissions.

Next, split these by business owner and cost centre. Assign your operations team ownership of Scope 1 furnaces, procurement for purchased materials, logistics for freight, and HR or travel for business aviation. For each cluster, list the available abatement levers and realistic timelines. Blast furnace steel? Hydrogen DRI projects are scaling through the late 2020s, so plan a supplier engagement strategy now and expect green steel premiums by 2030. Cement? CCUS pilots are advancing, but commercial scale is later in the decade. International shipping? Shipping requires $2 trillion over 30 years for zero-emission fuel production and vessels , so expect this to remain hard to abate longer.

Finally, score each cluster by impact (tCO₂e), feasibility (technology readiness, cost, supplier availability), and time to implement (aligned to your asset and contract cycles). Prioritise quick wins like efficiency improvements and low-carbon procurement in categories with emerging supply, while flagging long-term bets where you'll need patient capital and acceptance of residual emissions. Turn this into an internal "hard-to-abate register" that feeds directly into your SBTi target-setting and capital planning discussions.

4. Decarbonisation pathways for hard to abate emissions: what's realistic by 2030–2040

The main solution buckets are well known: efficiency and process optimisation (available now, often with short paybacks), electrification with renewable power (viable for lower-temperature processes and some transport, scaling rapidly), green hydrogen and e-fuels (pilots and first commercial projects starting mid-2020s, large-scale deployment through the 2030s), CCUS (critical for cement and some chemical processes, industrial hubs scaling this decade), and circularity and material efficiency (reducing demand structurally, applicable today).

Stegra's hydrogen-powered DRI plant in Boden, Sweden will feature a 700 MW electrolyser and produce 2.5 Mtpa green steel; phase 1 production starts 2026 with total investment of €6.5 billion . Meranti's 2.5 Mtpa DRI plant in Oman will ramp from natural gas to 100% green hydrogen by 2045 . These examples show green steel is moving from lab to reality, but the economics and scale will take the full decade to mature.

The US DOE allocated over $12 billion for industrial CCUS demonstrations across 11 sectors , signalling that capture technology is a priority for process-heavy industries. Meanwhile, circular economy measures in EU heavy industries could cut 189–231 MtCO₂e per year, nearly 15% of EU total emissions , proving that demand-side interventions can structurally reduce what you consider hard to abate.

Translate these pathways into corporate planning by tying each hard-to-abate cluster to 2030 and 2040 reduction expectations. For steel, assume access to some green supply by 2030 but full transition by 2040. For aviation, SAF will grow but won't eliminate all emissions by 2030; plan for residual emissions and removal credits. For cement in your supply chain, engage suppliers on CCUS roadmaps and accept that clinker will remain partially hard to abate through 2035. Explicitly flag in your transition plan where you expect unavoidable emissions within your planning horizon versus residual emissions at net-zero, and link these to internal carbon pricing to drive investment.

5. Managing residual hard to abate emissions with high-integrity carbon removal credits

When – and when not – to use carbon removal credits for hard to abate emissions

Carbon credits play two roles: near-term beyond-value-chain mitigation while you decarbonise, and from your net-zero year onwards, neutralising true residual emissions with carbon removal credits, in line with SBTi and WRI guardrails. Credits must never substitute for feasible abatement, and overuse is now explicitly criticised by leading frameworks.

Use credits for beyond-value-chain mitigation (BVCM) today to support scaling of removal technologies and demonstrate climate leadership, but keep this clearly separate from your science-based reduction targets. At your net-zero year, any emissions still entering the atmosphere after all feasible abatement must be counterbalanced with permanent carbon dioxide removals—not short-lived offsets. That distinction is critical for audit and stakeholder credibility.

Building an audit-ready, CSRD-aligned approach in the context

Quality is non-negotiable. Your credits need strong additionality (the removal wouldn't happen without the carbon finance), robust permanence (stored for centuries, not decades, with clear reversal risk management), conservative baselines that don't overestimate impact, minimal leakage, and credible MRV with third-party verification. Add safeguards for biodiversity and communities, and you have a checklist that aligns with the Oxford Principles, ICVCM Core Carbon Principles, and VCMI Claims Code.

CSRD ESRS E1-7 mandates disclosure of GHG removals from in-value-chain projects and emissions reductions financed via carbon credits . That means you'll need to document not just how many tonnes you bought, but the quality criteria you applied, the methodologies used, third-party ratings, and how you avoid double-counting. German courts and the upcoming EU Green Claims Directive demand that any "climate neutral" or net-zero claim is backed by detailed, verifiable evidence. Senken's Sustainability Integrity Index, which evaluates 600+ data points per project, operationalises these criteria into portfolios that come with full traceability from purchase to retirement—exactly what your auditors and CSRD assurance provider will ask for.

.svg)