ESG stands for Environmental, Social and Governance – a framework businesses use to measure, manage and report on material sustainability risks and impacts that affect both financial performance and the world around them. If you're leading sustainability, you already know ESG isn't a nice-to-have anymore. Your board wants to see how ESG connects to enterprise risk. Investors are asking tougher questions about your climate data and carbon credit quality. And CSRD has turned ESG reporting from a voluntary exercise into a legal requirement with real audit trails and enforcement teeth.

The challenge? Most ESG content still treats it like a concept to understand, not a system to run. This guide is different. We'll walk through what ESG actually means under EU double materiality rules, how to operationalise it across your organisation with clear governance and data processes, and – critically – how to handle the climate piece without greenwashing risk. Around 90% of empirical studies show ESG performance correlates positively with financial results, yet high ESG scores also correlate with greenwashing incidents. The difference? Rigorous data, transparent methodology, and a practical roadmap that turns ESG from a reporting burden into a strategic advantage.

What does ESG cover?

In practice, Environmental covers climate, energy, water, waste, biodiversity and pollution. Social includes labour rights, diversity, health and safety, community relations and supply chain conditions. Governance spans board structure, executive accountability, anti-corruption, business ethics and shareholder rights. Under EU rules, particularly CSRD and ESRS, each pillar translates into mandatory disclosure requirements tied to double materiality: you report both how sustainability matters financially impact your business and how your operations impact people and the planet.

The evidence base for taking ESG seriously is robust. A meta-analysis of over 2,200 empirical studies found that roughly 90% reported a non-negative relationship between ESG performance and corporate financial outcomes, with the majority showing positive effects on long-term value creation. This isn't philanthropy; it's risk management and competitive positioning. Stakeholder capitalism, the idea that sustainable enterprise value must be created for all principal stakeholders, not just shareholders, now shapes how boards and investors think about business resilience and growth.

For DACH sustainability leaders, that means ESG is no longer optional or reputational. It's woven into CSRD reporting cycles, investor due diligence, credit assessments and increasingly, customer procurement criteria. The question isn't whether to do ESG, but how to operationalise it rigorously across your entities, functions and data systems.

What ESG means under CSRD, ESRS and double materiality for companies

CSRD and the European Sustainability Reporting Standards effectively define what ESG must cover for large undertakings in scope. The first set of ESRS, adopted in 2023, includes twelve sector-agnostic standards spanning environmental, social and governance topics. For most corporates, ESRS E1 on climate change is central: you're required to report gross Scope 1, 2 and 3 GHG emissions, disclose your decarbonisation pathway, and separately account for any GHG removals or mitigation projects financed through carbon credits.

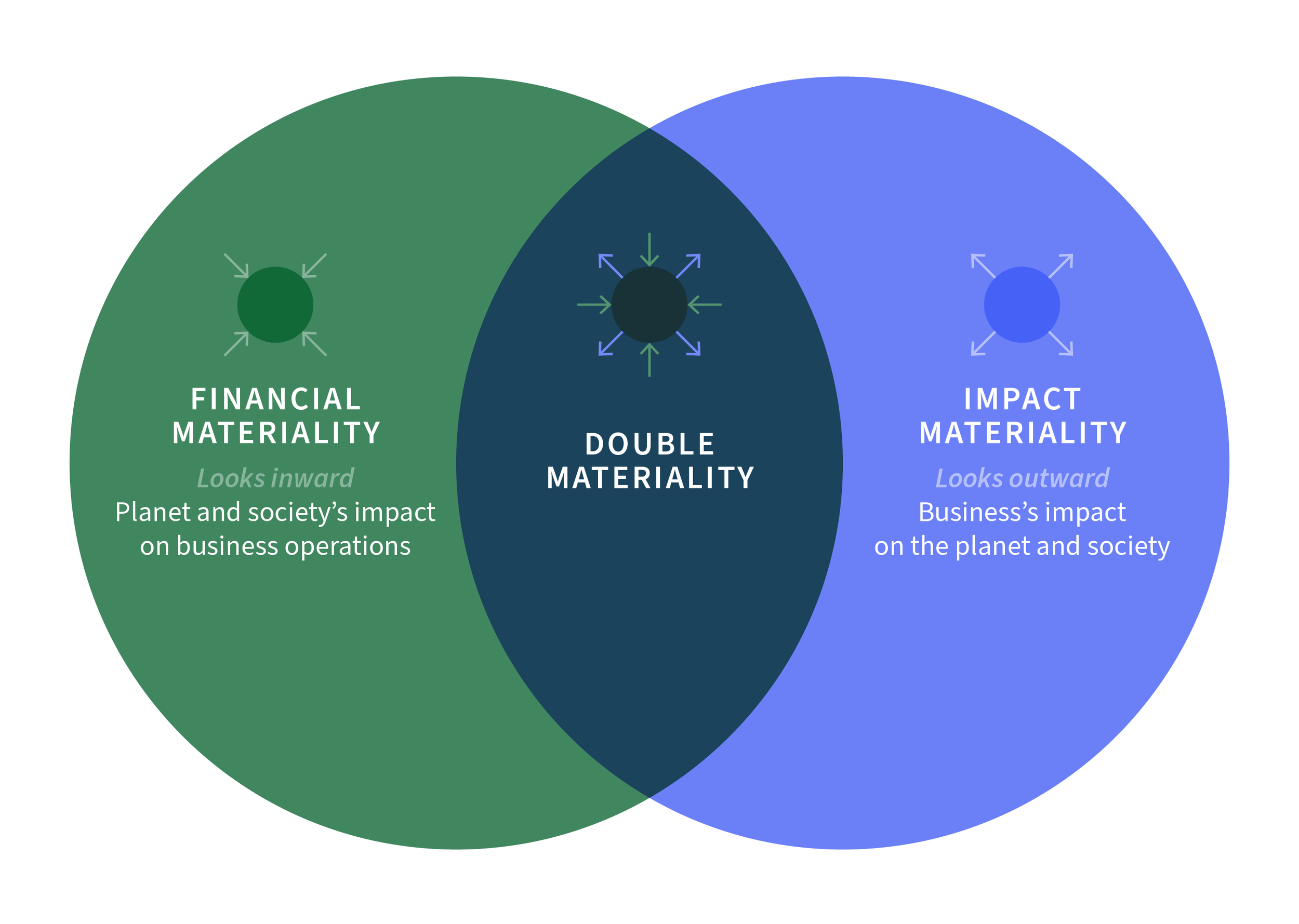

Double materiality is the key concept that reshapes how you prioritise ESG topics. You assess both financial materiality (which sustainability risks and opportunities affect your enterprise value, cash flows or cost of capital over short, medium and long term) and impact materiality (where your operations, value chain and products significantly impact people, communities or ecosystems). A topic is material if it meets either threshold; many topics, like climate for most industrial and service companies, meet both.

In practice, this means your materiality assessment drives your ESRS disclosure obligations. Climate almost always emerges as financially and impact material, triggering ESRS E1 requirements. Social topics such as own workforce conditions (ESRS S1) or value chain labour rights (ESRS S2) and governance matters like business conduct (ESRS G1) follow based on your sector, footprint and stakeholder concerns. EFRAG's simplified ESRS, drafted in late 2025, reduces datapoint burden by 68% for smaller in-scope companies, but the double materiality principle and core climate, social and governance coverage remain.

.png)

For you as Head of Sustainability, this regulatory clarity is useful: it gives you a mandate to build cross-functional ESG processes, secure budget for data systems, and frame ESG in the language of compliance and enterprise risk that resonates with finance and the board.

Turning ESG into an operating system: governance, roles and processes

Moving ESG from a reporting task to an operating system requires clear governance, explicit roles and repeatable processes. In large, multi-entity organisations, ESG work typically spans sustainability, finance, risk, HR, procurement, legal and investor relations. Without agreed ownership, data gets duplicated, gaps appear, and audit readiness suffers.

Leading companies assign board-level oversight to a dedicated ESG or sustainability committee or to the nominating and governance committee. Around 63% of S&P 500 firms assign primary ESG oversight to governance committees, and 51% involve multiple committees or the full board. At management level, an executive ESG committee with representatives from sustainability, finance, risk, operations, HR and procurement ensures cross-functional coordination. A disclosure committee, increasingly common for CSRD, coordinates data collection, validation and sign-off across business units and geographies.

A pragmatic sequence to maintain ESG alignment looks like this:

- Run or update your double materiality assessment annually or when significant business changes occur, engaging internal and external stakeholders to identify financially and impact material topics.

- Map ESG topics to enterprise risk categories (strategic, operational, compliance, reputational) so CFO, CRO and the board see ESG through their existing risk appetite and control frameworks.

- Agree a focused list of 5–10 priority ESG topics, typically led by climate for most DACH industrials, logistics, finance and services firms, plus key social and governance themes relevant to your sector.

- Assign data owners and process owners for each material topic across entities: who collects energy and emissions data, who tracks diversity metrics, who manages supplier audits, and who consolidates and controls it for CSRD-grade external reporting.

This structure isn't bureaucracy; it's how you make ESG auditable, repeatable and scalable across thousands of employees and multiple legal entities. Companies like Telefónica tie climate performance to variable compensation and provide staff training; Cellnex uses a cross-functional ESG committee of People, Operations, Governance, Sustainability and Investor Relations; Siemens embeds ESG into product design and incentive structures through its DEGREE framework. The common thread is clarity on who owns what and how ESG decisions flow through governance.

Climate integrity at the core of ESG: emissions, targets and carbon credits

For the vast majority of companies, climate is the most financially and impact material ESG topic. Under ESRS E1, high-integrity climate action means full Scope 1, 2 and 3 GHG inventories, science-based decarbonisation targets aligned with limiting warming to 1.5°C, and transparent, separate reporting of gross emissions versus any removals or compensation via carbon credits.

What ESG meaning implies for your climate and carbon-credit strategy

ESG credibility on climate starts with robust Scope 1–3 accounting: direct emissions from operations, purchased energy, and the full value chain from suppliers to product use and end-of-life. ESRS E1-6 requires you to disclose these in metric tonnes CO₂ equivalent. ESRS E1-7 goes further: you must report GHG removals and mitigation projects financed through carbon credits separately from your gross emissions baseline. This prevents "netting off" low-quality offsets against unabated emissions, a practice that regulators and NGOs increasingly challenge as greenwashing.

Science-based target frameworks, particularly SBTi's evolving Net-Zero Standard 2.0, emphasise deep operational cuts first. SBTi now expects companies to achieve substantial Scope 1 and 2 reductions and ambitious Scope 3 engagement before relying on carbon credits, and even then, only high-quality removals with long-term permanence should play a role. Initiatives like the Carbon Data Open Protocol aim to harmonise carbon credit data standards by end 2025, signalling that traceability, additionality and documentation are becoming non-negotiable.

In practical terms, this means your carbon credit strategy must rest on rigorous due diligence. Many credits on the market fail basic integrity tests: research shows that 84% of credits carry high risk, and 68% of DAX40 companies that purchased offsets ended up supporting projects with little real climate impact. To avoid this, use multiple layers of verification: registry standards (Verra, Gold Standard, Puro.earth), independent MRV, third-party audits and external rating agencies like BeZero or Sylvera.

Senken's Sustainability Integrity Index applies over 600 datapoints across project fundamentals, carbon impact (additionality, permanence, leakage), co-benefits, reporting transparency and compliance reputation. Only the top 5% of projects pass this screening, ensuring CSRD-ready documentation, alignment with ICVCM Core Carbon Principles, and defensibility under audit. For DACH sustainability leaders balancing board pressure for net-zero claims with regulatory and reputational risk, this data-driven approach de-risks your climate compensation and keeps your ESG narrative credible.

Data, ratings and greenwashing: building ESG that stands up to scrutiny

ESG ratings and scores are built from underlying datasets, weightings and methodologies that vary widely across providers like MSCI, Sustainalytics, FTSE Russell and regional agencies. Missing data is common, differences in data cleaning and indicator selection are large, and correlations between major rating agencies remain low. Research on ESG data quality shows that high scores can even correlate positively with reported greenwashing incidents, meaning optics don't guarantee substance.

For you as a practitioner, this divergence has a clear implication: **focus on your core set of high-quality, auditable metrics aligned with **CSRD, rather than chasing every external rating. Investors increasingly look past headline scores to examine your actual climate trajectory, social KPIs and governance controls. Strong ESG performance is about reliable data, transparent methodology and evidence-backed claims, not gaming third-party rankings.

To reduce greenwashing risk and build ESG resilience, adopt these practices:

- Tighten claim boundaries: If you say "carbon neutral operations," define scope (Scope 1+2 only? which entities?) and method (reductions vs credits) explicitly in footnotes and sustainability reports.

- Document methodologies and assumptions: Maintain an audit trail for emission factors, allocation rules, materiality thresholds and credit quality criteria. Regulators and auditors will ask for it.

- Use conservative language: Avoid absolute claims like "climate neutral" or "net zero" unless you meet the full SBTi Net-Zero Standard and can evidence deep, verified reductions across all scopes. Terms like "residual emissions compensated with high-quality removals" are more defensible.

- Seek independent verification: Third-party limited or reasonable assurance on climate data and, where possible, certification of carbon credit quality (ICVCM CCP label, independent ratings) strengthens credibility.

- Publish full transparency on carbon credits: Disclose project names, registries, methodologies, vintage, retirement certificates and quality due diligence in annexes or online trackers. CSRD expects this level of detail.

Recent enforcement underscores the stakes: a major German asset manager faced a €25 million fine in 2025 for overstating ESG integration, the U.S. SEC fined an investment adviser $1.5 million for misrepresenting ESG reviews, and courts have ruled against corporate climate campaigns deemed misleading. The EU's common definition of greenwashing warns that sustainability claims not fairly reflecting underlying substance mislead stakeholders. With the Empowering Consumers for the Green Transition Directive banning vague environmental claims from September 2026, the compliance bar is rising fast. Treat ESG data quality and claim substantiation as legal and reputational risk management, not just best practice.

.svg)